Lammas Day – the first day of August. School holidays, warm weather, beach visits, perhaps a swim in the sea? Or, on a windy cloudy day, a walk; a beach walk. At low to mid tide it is possible to follow the beach all the way between Lowestoft and Southwold on the north Suffolk coast without ever venturing inland. The coast along this stretch of the North Sea foreshore is a mixture of sand and shingle, with low cliffs and the occasional freshwater broad lying perilously close to the ever advancing tide. At odds with the gentle agricultural landscape of the hinterland the coast here is an uncompromising full stop in the landscape: a sudden transition from land to sea. Far to the east, beyond the horizon, are the European Low Countries that were once so closely tied, economically, and culturally, to this region. Lowland – sea bed – low land: the North Sea (WG Sebald’s ‘German Ocean’ in The Rings of Saturn) is but a watery interruption in the flow of things, both a barrier and a conduit for the movement of humans and goods.  I set out from Kessingland, just south of Lowestoft, where a large expanse of dunes and shingle separates the sea from the holiday homes and caravans that line the low clifftop like racing cars at a starting grid preparing to rush towards the sea. Truth be told, there is little in the way to stop them. It may be August but even now the beach is relatively quiet – just a few families and dog-walkers clambering over the dunes to reach the sea, which today is grey, grumpy and not particularly welcoming. The Kessingland littoral is distinguished by its specialist salt-tolerant flora: sea holly, sea pea, sea campion, sea beet – in fact, place a ‘sea’ in front of any common plant name and there is a good chance that such a species will exist and flourish here. Also rooted into the shingle, thriving on little more than sunshine and salt spray, are clumps of yellow-horned poppies with long twisting seed pods. The poppies are mostly past their flowering peak but elsewhere, where there is a thin veneer of soil to root into, colour is provided by stands of rosebay willow herb – a rich purple layer of distraction between the straw-hued shingle and the cloud-heavy sky, both washed of colour in the flat coastal light.

I set out from Kessingland, just south of Lowestoft, where a large expanse of dunes and shingle separates the sea from the holiday homes and caravans that line the low clifftop like racing cars at a starting grid preparing to rush towards the sea. Truth be told, there is little in the way to stop them. It may be August but even now the beach is relatively quiet – just a few families and dog-walkers clambering over the dunes to reach the sea, which today is grey, grumpy and not particularly welcoming. The Kessingland littoral is distinguished by its specialist salt-tolerant flora: sea holly, sea pea, sea campion, sea beet – in fact, place a ‘sea’ in front of any common plant name and there is a good chance that such a species will exist and flourish here. Also rooted into the shingle, thriving on little more than sunshine and salt spray, are clumps of yellow-horned poppies with long twisting seed pods. The poppies are mostly past their flowering peak but elsewhere, where there is a thin veneer of soil to root into, colour is provided by stands of rosebay willow herb – a rich purple layer of distraction between the straw-hued shingle and the cloud-heavy sky, both washed of colour in the flat coastal light.  Further south, the cliffs grow a little higher. Ferrous red and as soft and powdery as halva, they are irredeemably at the mercy of the North Sea tide. And it shows: the cliffs are raw and freshly cleaved, with collapsed chunks that have been further eroded by the incoming tide such that they appear to seep from the cliff bases like congealed gravy. Man-made objects receive no preferential treatment – a collapsed WWII concrete defence bunker slopes between cliff and sand at one point, its long process of total disintegration still in its infancy as its perches ignominiously at 45 degrees, an involuntary buttress for the flaking cliffs.

Further south, the cliffs grow a little higher. Ferrous red and as soft and powdery as halva, they are irredeemably at the mercy of the North Sea tide. And it shows: the cliffs are raw and freshly cleaved, with collapsed chunks that have been further eroded by the incoming tide such that they appear to seep from the cliff bases like congealed gravy. Man-made objects receive no preferential treatment – a collapsed WWII concrete defence bunker slopes between cliff and sand at one point, its long process of total disintegration still in its infancy as its perches ignominiously at 45 degrees, an involuntary buttress for the flaking cliffs.

The cliffs may be ephemeral geomorphology, constantly pushed back by the eroding tide, but they possess enough permanence for colonies of sand martins to pit them with nesting burrows high up the cliff face. The birds swoop and chatter in high-pitched whispers as they gather flies above the shingle, flying in and out their nest holes faster than the eye can bring itself into focus.

Further along, a red-brick building lies in an even more advanced state of breakdown. Dead trees, devoid of bark and bleached pale by saltwater protrude from the sand. Some stand roots-proud with their upper trunks planted in the sand as if drawing nutrition from deep underground. Others are inverted stumps that appear to channel the centrepiece of north Norfolk’s sacred Seahenge, upturned roots on display like rustic altars.

The tide is still going out, revealing new treasures on the wet smooth sand. Footprints ahead of me heading south look like my own but, of course, they are not – I have not been there yet. The unidentified boot-print doppelganger must be far ahead of me. One of the imprints has narrowly missed a solitary beached jellyfish, red-veined and otherworldly. Soon I notice more jellyfish on the tideline: unveined, translucent specimens that stare up from the sand like the detached iris of a giant’s eye.

The tide is still going out, revealing new treasures on the wet smooth sand. Footprints ahead of me heading south look like my own but, of course, they are not – I have not been there yet. The unidentified boot-print doppelganger must be far ahead of me. One of the imprints has narrowly missed a solitary beached jellyfish, red-veined and otherworldly. Soon I notice more jellyfish on the tideline: unveined, translucent specimens that stare up from the sand like the detached iris of a giant’s eye.

Approaching Southwold, the pier stretching out to sea becomes clearer in detail. The town’s white lighthouse flashes in warning. Beyond the resort, a few miles further south, the gargantuan golf ball of Sizewell B glows uncannily white. Halfway between sea and cliff on the freshly revealing sand are miscellaneous concrete blocks, remains of footings, moorings, buildings. Some of these have been almost completely submerged by sand to leave a line of tiny pyramids like the vertebra of a buried dragon. Frame the scene carefully and squint and this might be an aerial view over the Egyptian desert. The lack of a viable sphinx and presence of a battered clifftop caravan soon disabuses such fantastical musing.

Southwold arrives – or, rather, I arrive there – the beach approach heralded by groynes and breakwaters. Then comes the first phalanx of the town’s famously expensive beach huts, a sink estate for solvent holiday makers who have succumbed to the Southwold equivalent of shed-envy. The huts trace a line along the seafront past the pier where a Punch and Judy show is underway, delighting a crowd of children and adults with good old-fashioned, non-PC entertainment that glosses over domestic violence and police brutality. “That’s the way to do it,” swazzles Mr Punch before exclaiming, “Lookout children, the Devil’s going to come and get you.” The Devil was, in fact, coming for Mr Punch yet is outwitted by the trickster anyway in the show’s denouement. Light entertainment, yet such darkness – the seaside has always taken liberties with propriety.

For more on this stretch of coast see my earlier post: At Covehithe

The far west of Norfolk between Terrington St John and Walsoken on the Cambridgeshire border is often referred to as Fen country but technically it is part of the Norfolk Marshland. John Seymour in his Companion Guide to East Anglia (1970) writes: “The Marshlands are not to be confused with the Fens. The Marshlands, nearer to the sea than the Fens, are of slightly higher land, not so subject to flooding, and have been inhabited from the earliest times”.

The far west of Norfolk between Terrington St John and Walsoken on the Cambridgeshire border is often referred to as Fen country but technically it is part of the Norfolk Marshland. John Seymour in his Companion Guide to East Anglia (1970) writes: “The Marshlands are not to be confused with the Fens. The Marshlands, nearer to the sea than the Fens, are of slightly higher land, not so subject to flooding, and have been inhabited from the earliest times”.  Like the Fens proper this is a region of wide horizons and big skies, a table-flat landscape of barley and mustard fields, of plantations of poplars and lonely farmsteads, of electricity pylons that march across the landscape like robotic sentinels. This is the countryside of

Like the Fens proper this is a region of wide horizons and big skies, a table-flat landscape of barley and mustard fields, of plantations of poplars and lonely farmsteads, of electricity pylons that march across the landscape like robotic sentinels. This is the countryside of  This region, along with the Fens to the west, is a Brexit stronghold where many bear a grudge towards the Eastern Europeans who come to work in the fields here. Antipathy to itinerant farm labourers is nothing new and Emneth, a village located hard against the Cambridgeshire border, has become particularly, and probably unfairly, infamous thanks to its Tony Martin connection. Interestingly, John Seymour, writing in the late 1960s, describes Emneth as having “one of the pubs in the Wisbech fruit-growing district that does not display the racialist (and illegal) sign: NO VAN DWELLERS, and consequently it is one of the pubs in which a good time may often be had”. They still grow fruit in the Wisbech district but I cannot vouch for the welcome currently proffered by its pubs.

This region, along with the Fens to the west, is a Brexit stronghold where many bear a grudge towards the Eastern Europeans who come to work in the fields here. Antipathy to itinerant farm labourers is nothing new and Emneth, a village located hard against the Cambridgeshire border, has become particularly, and probably unfairly, infamous thanks to its Tony Martin connection. Interestingly, John Seymour, writing in the late 1960s, describes Emneth as having “one of the pubs in the Wisbech fruit-growing district that does not display the racialist (and illegal) sign: NO VAN DWELLERS, and consequently it is one of the pubs in which a good time may often be had”. They still grow fruit in the Wisbech district but I cannot vouch for the welcome currently proffered by its pubs.

This was bear country. No doubt about it. Over breakfast Alfred from the guesthouse had said, “You should make sure that you talk when you go walking there – or maybe sing – that way you won’t take them by surprise. My wife and I saw a mother bear with cubs in those woods earlier this year but don’t worry too much, just make sure that you don’t take them by surprise.”

This was bear country. No doubt about it. Over breakfast Alfred from the guesthouse had said, “You should make sure that you talk when you go walking there – or maybe sing – that way you won’t take them by surprise. My wife and I saw a mother bear with cubs in those woods earlier this year but don’t worry too much, just make sure that you don’t take them by surprise.” The drizzle had stopped by the time we left the guesthouse to walk east along the bank of the Valbona River. The day before we had come across four snakes in the space of a couple of hours, including a sluggish horn-nosed viper that had the tail of an unfortunate lizard protruding from its mouth, but today, perhaps because of the lack of warm sunshine, they were nowhere to be seen. Undoubtedly they were still close by, skulking beneath rocks, sleeping the deep reptilian sleep that comes with the digestion of a heavy meal… of reptiles. No snakes, but we did see an extraordinary large lizard – a European green lizard (Lacerta viridis) as we later identified it – with strikingly beautiful markings that morphed like a potter’s glaze from sky blue on the head to copper-stain green along its back and tail. Among our fellow guests at the guesthouse were a couple of German amateur herpetologists and, confronted by reptilian magnificence as this, it was easy to understand the appeal. Bear country it may have been but this was snake and lizard territory too.

The drizzle had stopped by the time we left the guesthouse to walk east along the bank of the Valbona River. The day before we had come across four snakes in the space of a couple of hours, including a sluggish horn-nosed viper that had the tail of an unfortunate lizard protruding from its mouth, but today, perhaps because of the lack of warm sunshine, they were nowhere to be seen. Undoubtedly they were still close by, skulking beneath rocks, sleeping the deep reptilian sleep that comes with the digestion of a heavy meal… of reptiles. No snakes, but we did see an extraordinary large lizard – a European green lizard (Lacerta viridis) as we later identified it – with strikingly beautiful markings that morphed like a potter’s glaze from sky blue on the head to copper-stain green along its back and tail. Among our fellow guests at the guesthouse were a couple of German amateur herpetologists and, confronted by reptilian magnificence as this, it was easy to understand the appeal. Bear country it may have been but this was snake and lizard territory too. In a meadow just beyond the footbridge that led across the racing river to the tiny hamlet of Čerem, stood a monument to Bajram Curri. Bajram Curri (pronounced ‘Tsuri’ like the English county rather than the universal Indian dish) also gave his moniker to the principal market town of this far northern border region of Albania, its name only 20 years ago a watchword for lawlessness and gun-running – a KLA stronghold that was more closely connected to what was then war-torn Kosovo than its own national capital in Tirana. These days, Bajram Curri is a quiet provincial town that only ever becomes animated on market days when hard-bargaining farmers might raise their voices over the price of sheep. Like the rest of Albania, it is now as safe as anywhere in Europe – safer probably – yet still there were those who looked askance whenever Albania was mentioned as if the country was still lawless and dangerous and run by shady mafia figures. It is not… but there are bears in the woods.

In a meadow just beyond the footbridge that led across the racing river to the tiny hamlet of Čerem, stood a monument to Bajram Curri. Bajram Curri (pronounced ‘Tsuri’ like the English county rather than the universal Indian dish) also gave his moniker to the principal market town of this far northern border region of Albania, its name only 20 years ago a watchword for lawlessness and gun-running – a KLA stronghold that was more closely connected to what was then war-torn Kosovo than its own national capital in Tirana. These days, Bajram Curri is a quiet provincial town that only ever becomes animated on market days when hard-bargaining farmers might raise their voices over the price of sheep. Like the rest of Albania, it is now as safe as anywhere in Europe – safer probably – yet still there were those who looked askance whenever Albania was mentioned as if the country was still lawless and dangerous and run by shady mafia figures. It is not… but there are bears in the woods. Further on a wooden sign pointed steeply uphill towards ‘The Cave of Bajram Curri’, the cave where the Albanian hero and patriot was said to have once taken refuge whilst fleeing his enemies. We followed this up through woodland for a short while before taking another path to the left that signposted the springs at Burumi i Picamelit. This track, marked by occasional red and white ciphers painted on trees like Polish flags, lead through dense beech woodland scattered with huge boulders that had long ago thundered down from the cliffs far above. It was an evocative place, a numinous realm of shade and fecundity – the light tinged green by filtration through the high leaf canopy and by the thick carpet of moss that coated every surface. Here and there were saprophytic ghost orchids poking through the coppery leaf mold – pale, bloodless plants that had no truck with the chlorophyll that otherwise permeated the woodland like a green miasma.

Further on a wooden sign pointed steeply uphill towards ‘The Cave of Bajram Curri’, the cave where the Albanian hero and patriot was said to have once taken refuge whilst fleeing his enemies. We followed this up through woodland for a short while before taking another path to the left that signposted the springs at Burumi i Picamelit. This track, marked by occasional red and white ciphers painted on trees like Polish flags, lead through dense beech woodland scattered with huge boulders that had long ago thundered down from the cliffs far above. It was an evocative place, a numinous realm of shade and fecundity – the light tinged green by filtration through the high leaf canopy and by the thick carpet of moss that coated every surface. Here and there were saprophytic ghost orchids poking through the coppery leaf mold – pale, bloodless plants that had no truck with the chlorophyll that otherwise permeated the woodland like a green miasma. The path eventually bypassed a glade where large moss- and fern-covered rocks formed a natural outdoor theatre. Dead dry branches snapped noisily underfoot as we made our way across to the largest of the rocks – silence was not an option and any lurking bears would have been duly warned of our intrusion by our clumsy, crunching progress. Growing high on one of the larger rocks was a solitary Ramonda plant, a small blue flower and rosette of leaves anchored to the moss. The plant had an air of rarity about it – and scarce it was: a member of a specialised family found only in the Balkans and Pyrenees. Growing in solitary isolation and providing a discrete focal point in this hidden glade it almost felt as if this delicate blue flower had lured us here – the trophy of a secret quest, an object of worship. Indeed, the whole glade had the feel of the sacred: an animist shrine or secret gathering place; the location for a parliament of bears perhaps?

The path eventually bypassed a glade where large moss- and fern-covered rocks formed a natural outdoor theatre. Dead dry branches snapped noisily underfoot as we made our way across to the largest of the rocks – silence was not an option and any lurking bears would have been duly warned of our intrusion by our clumsy, crunching progress. Growing high on one of the larger rocks was a solitary Ramonda plant, a small blue flower and rosette of leaves anchored to the moss. The plant had an air of rarity about it – and scarce it was: a member of a specialised family found only in the Balkans and Pyrenees. Growing in solitary isolation and providing a discrete focal point in this hidden glade it almost felt as if this delicate blue flower had lured us here – the trophy of a secret quest, an object of worship. Indeed, the whole glade had the feel of the sacred: an animist shrine or secret gathering place; the location for a parliament of bears perhaps? We looked for evidence of ‘bear trees’ and eventually we found it: beside the track we discovered a conifer that had a large patch of bark missing from its trunk, freshly removed by the action of claw sharpening – or maybe as some sort of territorial signifier. At the junction of tracks further on was more visceral evidence in the form of a footpath sign that has been quite brutally attacked by a bear (or bears), the support post whittled away to a fraction of its former girth by unseen fearsome claws. Why this post had more bear-appeal than live growing trees of similar size was a mystery. Did bears have a preference for scratching away at machined timber? Was the unnatural square profile of the post especially tempting? Or did the bears somehow understand what signposts were for – to direct clod-footed human walkers into their territory. Fanciful and absurdly anthropomorphic though this might seem it did somehow hint at a thinly disguised warning – a re-purposing of man-made signposts to advertise the bears’ own potential threat: ursine semiotics. The day had, of course, been characterised by a total absence of bears – and woodpeckers too, despite numerous dead trunks riddled with their excavated holes – but their unseen presence in this secretive bosky world was nonetheless all too tangible. All the signs were there to be read.

We looked for evidence of ‘bear trees’ and eventually we found it: beside the track we discovered a conifer that had a large patch of bark missing from its trunk, freshly removed by the action of claw sharpening – or maybe as some sort of territorial signifier. At the junction of tracks further on was more visceral evidence in the form of a footpath sign that has been quite brutally attacked by a bear (or bears), the support post whittled away to a fraction of its former girth by unseen fearsome claws. Why this post had more bear-appeal than live growing trees of similar size was a mystery. Did bears have a preference for scratching away at machined timber? Was the unnatural square profile of the post especially tempting? Or did the bears somehow understand what signposts were for – to direct clod-footed human walkers into their territory. Fanciful and absurdly anthropomorphic though this might seem it did somehow hint at a thinly disguised warning – a re-purposing of man-made signposts to advertise the bears’ own potential threat: ursine semiotics. The day had, of course, been characterised by a total absence of bears – and woodpeckers too, despite numerous dead trunks riddled with their excavated holes – but their unseen presence in this secretive bosky world was nonetheless all too tangible. All the signs were there to be read.

We ventured on to visit the springs at Burumi i Picamelit where underground water emerged straight from the limestone to race downhill in a fury towards the Valbona River below. Tucked away in a crevice beneath one of the rocks was another Ramonda growing just inches from the fast-flowing water.

We ventured on to visit the springs at Burumi i Picamelit where underground water emerged straight from the limestone to race downhill in a fury towards the Valbona River below. Tucked away in a crevice beneath one of the rocks was another Ramonda growing just inches from the fast-flowing water. Heading back we become temporarily lost in the woods and spend ten minutes walking in circles looking for the trail before finally rediscovering it. Shortly after, we met the German reptile enthusiasts from the guesthouse walking the other way. We stopped to compare notes. None of us had seen any sign of bears in the flesh (in the fur?) but we had all seen the evidence that beckoned us: the claw-scratched trees, the mauled signpost. We concurred that it was probably best that way: an absence of bears on the ground but a strong sense of their presence as we politely trespassed their territory.

Heading back we become temporarily lost in the woods and spend ten minutes walking in circles looking for the trail before finally rediscovering it. Shortly after, we met the German reptile enthusiasts from the guesthouse walking the other way. We stopped to compare notes. None of us had seen any sign of bears in the flesh (in the fur?) but we had all seen the evidence that beckoned us: the claw-scratched trees, the mauled signpost. We concurred that it was probably best that way: an absence of bears on the ground but a strong sense of their presence as we politely trespassed their territory.

Still reeling from the solar onslaught of the Sun Ra Arkestra the previous night we travelled yesterday to Great Yarmouth to see The Tempest at the town’s Hippodrome Theatre. The

Still reeling from the solar onslaught of the Sun Ra Arkestra the previous night we travelled yesterday to Great Yarmouth to see The Tempest at the town’s Hippodrome Theatre. The  The Tempest took place in another very singular space: the wonderful

The Tempest took place in another very singular space: the wonderful  If the exterior seems full of promise, the interior is even more beguiling: all dark velvet and chocolate brown, and a warm, well-used ambience that has left a rich patina on the fabric of the place. The seating is snug and steeply tiered; its darkly lit corridors lined with old posters and portraits of clowns and past performers, most notably Houdini (where better than Great Yarmouth to demonstrate the art of escapology?). There is even a poster of Houdini in the gents and, while a male toilet in Great Yarmouth is probably not normally the wisest place to take out a camera, my fellow micturators seemed to understand my photographic purpose.

If the exterior seems full of promise, the interior is even more beguiling: all dark velvet and chocolate brown, and a warm, well-used ambience that has left a rich patina on the fabric of the place. The seating is snug and steeply tiered; its darkly lit corridors lined with old posters and portraits of clowns and past performers, most notably Houdini (where better than Great Yarmouth to demonstrate the art of escapology?). There is even a poster of Houdini in the gents and, while a male toilet in Great Yarmouth is probably not normally the wisest place to take out a camera, my fellow micturators seemed to understand my photographic purpose.  Theatre in the round; theatre in the wet: the Hippodrome might have been made for The Tempest; or, given a bit of temporal elasticity that could anticipate three hundred years into the future, The Tempest for the Hippodrome. The production, directed by William Galinsky, Artistic Director of the

Theatre in the round; theatre in the wet: the Hippodrome might have been made for The Tempest; or, given a bit of temporal elasticity that could anticipate three hundred years into the future, The Tempest for the Hippodrome. The production, directed by William Galinsky, Artistic Director of the  Shakespeare is reliably universal of course, but did I detect a whiff of Tarkovsky (Solaris, Stalker) in there? A hint too of Samuel Beckett? Of course, we each bring our own cultural references to bear. Today, yesterday’s performance seems almost dreamlike – a short-lived transportation from reality in which both the drama and the unique properties of the venue itself had an equal part to play. As Prospero remarks:

Shakespeare is reliably universal of course, but did I detect a whiff of Tarkovsky (Solaris, Stalker) in there? A hint too of Samuel Beckett? Of course, we each bring our own cultural references to bear. Today, yesterday’s performance seems almost dreamlike – a short-lived transportation from reality in which both the drama and the unique properties of the venue itself had an equal part to play. As Prospero remarks:

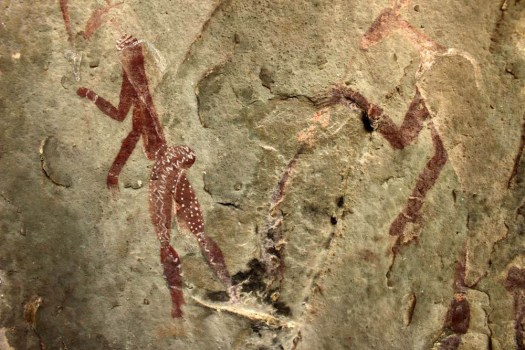

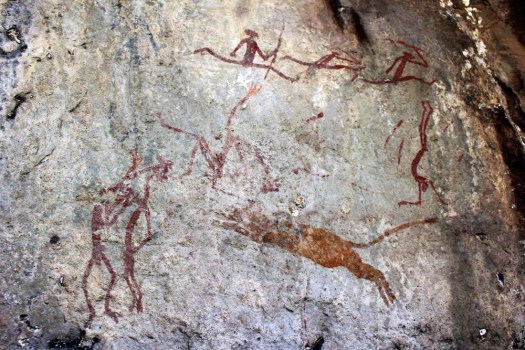

One of the highlights of my recent trip to South Africa was to see some really well-preserved rock art. The cave paintings were made by the San people, the hunter-gatherers who inhabited the Drakensberg mountain region in KwaZulu-Natal province close to the Lesotho border before the incoming Zulus drove them from the land. The rock paintings date from between 2,000 and 200 years ago and the best preserved are those found in south-facing caves where there is never any direct sunlight. One such cave is that found beneath Lower Mushroom Rock in the central Drakensberg.

One of the highlights of my recent trip to South Africa was to see some really well-preserved rock art. The cave paintings were made by the San people, the hunter-gatherers who inhabited the Drakensberg mountain region in KwaZulu-Natal province close to the Lesotho border before the incoming Zulus drove them from the land. The rock paintings date from between 2,000 and 200 years ago and the best preserved are those found in south-facing caves where there is never any direct sunlight. One such cave is that found beneath Lower Mushroom Rock in the central Drakensberg. The figures show hunting scenes involving various animals indigenous to the region, like eland, which are still numerous, and lions, which are no longer found here. Other paintings depict animal skin-wearing shamans in trances, a state of mind artificially (and partially chemically) induced to connect them with the spirit world in order to foresee the future and cure illnesses.

The figures show hunting scenes involving various animals indigenous to the region, like eland, which are still numerous, and lions, which are no longer found here. Other paintings depict animal skin-wearing shamans in trances, a state of mind artificially (and partially chemically) induced to connect them with the spirit world in order to foresee the future and cure illnesses. The paintings were made using brushes made from animal hair and dyes and pigments extracted from indigenous plants and mineral-rich rocks. The colour and attention to detail of the paintings are remarkable, and even depict the typically steatopygic buttocks characteristic of the San bushmen who nowadays mostly occupy the arid regions of Botswana and Namibia.

The paintings were made using brushes made from animal hair and dyes and pigments extracted from indigenous plants and mineral-rich rocks. The colour and attention to detail of the paintings are remarkable, and even depict the typically steatopygic buttocks characteristic of the San bushmen who nowadays mostly occupy the arid regions of Botswana and Namibia.

My feature on walking part of the Kumano Kodō pilgrimage trail in Japan will be published in a few days time in Elsewhere journal. Elsewhere is a Berlin-based print journal, published twice a year, dedicated to writing and visual art that explores the idea of place in all its forms, whether city neighbourhoods or island communities, heartlands or borderlands, the world we see before us or landscapes of the imagination.

My feature on walking part of the Kumano Kodō pilgrimage trail in Japan will be published in a few days time in Elsewhere journal. Elsewhere is a Berlin-based print journal, published twice a year, dedicated to writing and visual art that explores the idea of place in all its forms, whether city neighbourhoods or island communities, heartlands or borderlands, the world we see before us or landscapes of the imagination.

One way of looking at this evocative, if mildly disturbing, place is as a hidden enclave populated with the ghosts of colonialism. Situated right in the middle of Kolkata, tucked away purdah-like from the mayhem of the city streets, the Park Street Cemetery seems like another world. It really is another world: one in which time has coalesced to leave a thick patina on the colonnades and obelisks that commemorate the colonists who created this tropical city in their own image. The colonials mostly died young – easy victims of the disease-ridden, febrile climate that characterised this distant outpost of the East India Company. In true Victorian manner, those who were unfortunate enough to die young and never be able to return to their temperate homeland were interred here in magnificent mausoleums among lush, very un-British vegetation – a tropical Highgate transposed a quarter-way round the world. The cemetery is reputed to be the largest Old World 19th-century Christian graveyard outside Europe. It is also one of the earliest non-church cemeteries, dating from the 1767 and built like much of Kolkata/Calcutta on low, marshy ground. The overall effect is one of Victorian Gothic, although there are also some notable flourishes of Indo-Saracenic vernacular that reflect the influence of Hindu temple architecture.

One way of looking at this evocative, if mildly disturbing, place is as a hidden enclave populated with the ghosts of colonialism. Situated right in the middle of Kolkata, tucked away purdah-like from the mayhem of the city streets, the Park Street Cemetery seems like another world. It really is another world: one in which time has coalesced to leave a thick patina on the colonnades and obelisks that commemorate the colonists who created this tropical city in their own image. The colonials mostly died young – easy victims of the disease-ridden, febrile climate that characterised this distant outpost of the East India Company. In true Victorian manner, those who were unfortunate enough to die young and never be able to return to their temperate homeland were interred here in magnificent mausoleums among lush, very un-British vegetation – a tropical Highgate transposed a quarter-way round the world. The cemetery is reputed to be the largest Old World 19th-century Christian graveyard outside Europe. It is also one of the earliest non-church cemeteries, dating from the 1767 and built like much of Kolkata/Calcutta on low, marshy ground. The overall effect is one of Victorian Gothic, although there are also some notable flourishes of Indo-Saracenic vernacular that reflect the influence of Hindu temple architecture.  Arriving at the gatehouse my name is recorded in a ledger by a lugubrious guard, an action that in itself carries the hint of entering some sort of forbidden zone, a place where the living are only tolerated and should not outstay their welcome. The cemetery seems largely deserted of visitors, although I do inadvertently stumble across a spot of surreptitious man-on-man action taking place in the deep shade of one of the tombs. Despite the funerary setting, there is nothing occult at work here, and I conclude that the young men are simply taking advantage of the privacy offered by the cemetery in this most crowded of all India’s overflowing mega cities. There are signs prohibiting ‘committing nuisance’ attached to some of the trees and I wonder if this is a warning against this sort of clandestine liaison, although in India the expression is usually a euphemism for public urination.

Arriving at the gatehouse my name is recorded in a ledger by a lugubrious guard, an action that in itself carries the hint of entering some sort of forbidden zone, a place where the living are only tolerated and should not outstay their welcome. The cemetery seems largely deserted of visitors, although I do inadvertently stumble across a spot of surreptitious man-on-man action taking place in the deep shade of one of the tombs. Despite the funerary setting, there is nothing occult at work here, and I conclude that the young men are simply taking advantage of the privacy offered by the cemetery in this most crowded of all India’s overflowing mega cities. There are signs prohibiting ‘committing nuisance’ attached to some of the trees and I wonder if this is a warning against this sort of clandestine liaison, although in India the expression is usually a euphemism for public urination.  There are, of course, those who take full advantage of the cemetery’s concentrated occult power – fakirs who use it for training apprentices by making them spend the night here alone, an experience that could never be a comfortable one however much one was inured to the idea of djinns being hyperactive after dark. Even for hard-nosed rationalists, the sense of the numinous here is quite tangible, and the cemetery is without doubt a thoroughly spooky place. This is true even in broad daylight when the taxi horns and traffic thrum from the manic thoroughfare of Mother Teresa Sarani (formerly Park Street; before that, Burial Ground Road) cuts through the trees to provide a background drone for the tuneless squawks of the urban crows and parakeets that loiter here.

There are, of course, those who take full advantage of the cemetery’s concentrated occult power – fakirs who use it for training apprentices by making them spend the night here alone, an experience that could never be a comfortable one however much one was inured to the idea of djinns being hyperactive after dark. Even for hard-nosed rationalists, the sense of the numinous here is quite tangible, and the cemetery is without doubt a thoroughly spooky place. This is true even in broad daylight when the taxi horns and traffic thrum from the manic thoroughfare of Mother Teresa Sarani (formerly Park Street; before that, Burial Ground Road) cuts through the trees to provide a background drone for the tuneless squawks of the urban crows and parakeets that loiter here.  Not requiring of any such thaumaturgic rite of passage, a short afternoon visit suits me just fine. I am left alone with just the crows for company – dark portentous forms that swirl and scatter in the trees above, occasionally coming down to perch scurrilously on the sarcophagi as if they were extras from an Edgar Allen Poe film adaptation. Indeed, this would be the perfect location for a Gothic horror film, especially one that required a steamy colonial setting. Park Street Cemetery is the sort of place where dead souls rising from the ground can seem a distinct possibility – an eerie realm where the hubris of the Raj confronted its own vulnerability and the sad ghosts of empire still linger.

Not requiring of any such thaumaturgic rite of passage, a short afternoon visit suits me just fine. I am left alone with just the crows for company – dark portentous forms that swirl and scatter in the trees above, occasionally coming down to perch scurrilously on the sarcophagi as if they were extras from an Edgar Allen Poe film adaptation. Indeed, this would be the perfect location for a Gothic horror film, especially one that required a steamy colonial setting. Park Street Cemetery is the sort of place where dead souls rising from the ground can seem a distinct possibility – an eerie realm where the hubris of the Raj confronted its own vulnerability and the sad ghosts of empire still linger.

What is it that draws us to the sea; to the coast, the beach? On hot days in summer the answer is fairly obvious: to sunbathe, to swim, to cool off in the sea. Hot summer days are not such a common commodity these days – not in the British Isles anyway – but, whatever the weather brings, people tend to be drawn to the coast like moths to lanterns.

What is it that draws us to the sea; to the coast, the beach? On hot days in summer the answer is fairly obvious: to sunbathe, to swim, to cool off in the sea. Hot summer days are not such a common commodity these days – not in the British Isles anyway – but, whatever the weather brings, people tend to be drawn to the coast like moths to lanterns. Perhaps it is part of an unwritten code of leisure etiquette, something that established itself in the British collective unconscious in Victorian times when those who could afford it caught trains to the newly developed resorts on the coast in order to take the air. The tradition persisted into the 20th century when, given more leisure time and improved public transport, the working classes too could enjoy the same privilege. Nowadays a trip to the coast is a commonplace activity: a Sunday outing, an hour or two spent strolling on the beach, exercising the dog, dragging the children away from the virtual Neverland of their electronic screens.

Perhaps it is part of an unwritten code of leisure etiquette, something that established itself in the British collective unconscious in Victorian times when those who could afford it caught trains to the newly developed resorts on the coast in order to take the air. The tradition persisted into the 20th century when, given more leisure time and improved public transport, the working classes too could enjoy the same privilege. Nowadays a trip to the coast is a commonplace activity: a Sunday outing, an hour or two spent strolling on the beach, exercising the dog, dragging the children away from the virtual Neverland of their electronic screens. But maybe there is something that lies deeper? Some sort of atavistic compulsion to gaze at the sea, to see where we come from, from land masses beyond the horizon, from the primal sludge of the seabed. An urge look at the edge of things where seawater limns the shore and shapes our green island. We are, after all, an island race.

But maybe there is something that lies deeper? Some sort of atavistic compulsion to gaze at the sea, to see where we come from, from land masses beyond the horizon, from the primal sludge of the seabed. An urge look at the edge of things where seawater limns the shore and shapes our green island. We are, after all, an island race. Either way, there is beauty on the beach. Sensuous ripples of sand adorned with calcium necklaces and bangles; the pure white glint of breaking waves. Serried ranks of breakers on the incoming tide, parallels of swell and surf creating a liquid stave for the ocean’s moonstruck music: swash and backwash, the gentle abrasion of pebbles, the faintest tinkle of dead bivalves.

Either way, there is beauty on the beach. Sensuous ripples of sand adorned with calcium necklaces and bangles; the pure white glint of breaking waves. Serried ranks of breakers on the incoming tide, parallels of swell and surf creating a liquid stave for the ocean’s moonstruck music: swash and backwash, the gentle abrasion of pebbles, the faintest tinkle of dead bivalves.

It was the day after the winter solstice – a bright sunny day with the wind from the south, the temperature mild. Conscious of the turning of the year, a last minute escape from the frenzied Christmas build-up seemed appropriate, even if just for a few hours. The north Norfolk coast beckoned – where better to go when days are at their shortest, when the sovereign reign of darkness is turned on its head and the world set aright once more?

It was the day after the winter solstice – a bright sunny day with the wind from the south, the temperature mild. Conscious of the turning of the year, a last minute escape from the frenzied Christmas build-up seemed appropriate, even if just for a few hours. The north Norfolk coast beckoned – where better to go when days are at their shortest, when the sovereign reign of darkness is turned on its head and the world set aright once more? Wells-next-the-Sea was already closing up for Christmas when I left it behind at midday. I followed the coast path east, skirting the salt marshes and mud flats, the pines of East Hills silhouetted on the northern horizon. Scolt Head Island aside – Norfolk’s most northerly territory a little further west, its Ultima Thule – this was the last tract of land at this longitude before reaching the North Pole that lay far beyond the horizon and sunken, sea-drowned Doggerland.

Wells-next-the-Sea was already closing up for Christmas when I left it behind at midday. I followed the coast path east, skirting the salt marshes and mud flats, the pines of East Hills silhouetted on the northern horizon. Scolt Head Island aside – Norfolk’s most northerly territory a little further west, its Ultima Thule – this was the last tract of land at this longitude before reaching the North Pole that lay far beyond the horizon and sunken, sea-drowned Doggerland.  Scattered at regular intervals, poking for invertebrates in the mud were redshanks, curlews and little egrets – the latter once a scarce bird in these parts but now commonplace thanks to climate change. Brent geese, Arctic natives wintering here on this soft-weather shore, were feeding in large groups in the salt marshes. Periodically, without much warning, and honking noisily – the wildest of sounds – they would take to the air to describe a low arc before landing again. A hen harrier, white-rumped and straight-winged, quartering the marshes seemed to go unnoticed by the geese. Focused on much smaller prey, the harrier presented no threat to them – this they knew.

Scattered at regular intervals, poking for invertebrates in the mud were redshanks, curlews and little egrets – the latter once a scarce bird in these parts but now commonplace thanks to climate change. Brent geese, Arctic natives wintering here on this soft-weather shore, were feeding in large groups in the salt marshes. Periodically, without much warning, and honking noisily – the wildest of sounds – they would take to the air to describe a low arc before landing again. A hen harrier, white-rumped and straight-winged, quartering the marshes seemed to go unnoticed by the geese. Focused on much smaller prey, the harrier presented no threat to them – this they knew.  The mildness of the winter was clear to see. This was late December yet gorse bushes were weighed down with mustard yellow blooms. The emerald early growth of Alexanders lined the path edge, and there was even a small, yellow-blushed mushroom, its umbel newly fruited, peering up from the grass. The recent rainfall was quite apparent too – water that had accumulated to render the surface of the path in places to a viscous gravy that made walking hard work.

The mildness of the winter was clear to see. This was late December yet gorse bushes were weighed down with mustard yellow blooms. The emerald early growth of Alexanders lined the path edge, and there was even a small, yellow-blushed mushroom, its umbel newly fruited, peering up from the grass. The recent rainfall was quite apparent too – water that had accumulated to render the surface of the path in places to a viscous gravy that made walking hard work.  After a couple of hours walking, Blakeney Church came into view on the low hill above the harbour, its tower a warning – or a comfort – to sailors of old on this stretch of coast without a lighthouse. Stopping briefly to eat a sandwich on the steps of a boat jetty, my back to the sea, a short-eared owl, another winter visitor, swooped silently past, its unseen quarry somewhere in the wind-rustled reeds.

After a couple of hours walking, Blakeney Church came into view on the low hill above the harbour, its tower a warning – or a comfort – to sailors of old on this stretch of coast without a lighthouse. Stopping briefly to eat a sandwich on the steps of a boat jetty, my back to the sea, a short-eared owl, another winter visitor, swooped silently past, its unseen quarry somewhere in the wind-rustled reeds.  Approaching Blakeney, the moon, almost full, rose over the sea as the sun started setting behind the low ridge that topped the winter wheat fields. It was only three o’clock but already the light was vanishing. But there was change afoot – from now on the days would gradually lengthen and, in perfect solar symmetry, the long winter nights would slowly begin to lose their dark authority.

Approaching Blakeney, the moon, almost full, rose over the sea as the sun started setting behind the low ridge that topped the winter wheat fields. It was only three o’clock but already the light was vanishing. But there was change afoot – from now on the days would gradually lengthen and, in perfect solar symmetry, the long winter nights would slowly begin to lose their dark authority.

A grey morning, late November; a blanket of thick, high-tog cloud slung over the wet flatlands of northeast Norfolk. The day begins serendipitously when, approaching the car park at Horsey Windpump, two distant grey shapes are spotted in a roadside field – grey forms that have enough about them to demand a second look. Binoculars reveal them to be common cranes, an ironic name even here in one of their few British strongholds.

A grey morning, late November; a blanket of thick, high-tog cloud slung over the wet flatlands of northeast Norfolk. The day begins serendipitously when, approaching the car park at Horsey Windpump, two distant grey shapes are spotted in a roadside field – grey forms that have enough about them to demand a second look. Binoculars reveal them to be common cranes, an ironic name even here in one of their few British strongholds. We had, in fact, come to Horsey for the seals. But first, a walk through the marshes alongside Horsey Mere, then to follow the channel of Waxham New Cut before crossing the coast road to Horsey Gap to reach the dunes and the beach. Close to Brograve Mill, a solitary marsh harrier was quartering the reed-beds on the opposite bank. The jackdaws that had gathered on the broken remains of its wooden sail flew off as we approached the mill. Long an icon of the Norfolk Broads, this photogenic ruin looked to be reaching critical mass in its ruination; the brickwork of its tower leaning, Pisa-like, in a losing battle with gravity.

We had, in fact, come to Horsey for the seals. But first, a walk through the marshes alongside Horsey Mere, then to follow the channel of Waxham New Cut before crossing the coast road to Horsey Gap to reach the dunes and the beach. Close to Brograve Mill, a solitary marsh harrier was quartering the reed-beds on the opposite bank. The jackdaws that had gathered on the broken remains of its wooden sail flew off as we approached the mill. Long an icon of the Norfolk Broads, this photogenic ruin looked to be reaching critical mass in its ruination; the brickwork of its tower leaning, Pisa-like, in a losing battle with gravity. The car park at Horsey Gap had its usual compliment of visitors – most folk do not want to have to walk far to fulfill their annual seal pup quota. Clearly it has been a good year for grey seals, with more than 300 newly born pups along this stretch of coast. Signs and plastic ribbon barriers do their best to encourage the over-inquisitive to keep at bay. Grey seals, despite their bulk, are the epitome of vulnerability. On land anyway – slumped on the beach liked huge slugs with lovable Labrador faces, their awkward obese bodies are an encumbrance out of the water.

The car park at Horsey Gap had its usual compliment of visitors – most folk do not want to have to walk far to fulfill their annual seal pup quota. Clearly it has been a good year for grey seals, with more than 300 newly born pups along this stretch of coast. Signs and plastic ribbon barriers do their best to encourage the over-inquisitive to keep at bay. Grey seals, despite their bulk, are the epitome of vulnerability. On land anyway – slumped on the beach liked huge slugs with lovable Labrador faces, their awkward obese bodies are an encumbrance out of the water. The beach action is minimal: an occasional clumsy rolling over; the odd shuffle forward using flippers for traction; sporadic barking and baring of teeth between rival males. The scene looks like an aftermath of overindulgence, bodies adrift on the beach sleeping off the effects of a heavy night. Perhaps it is all that hyper-rich seal milk that explains this torpor: the effort the pups take to digest the 60%-fat fluid, the energy involved in the cows’ synthesising the milk from a diet of fish? Such extreme inactivity brings to mind an assembly of turkey dinner-replete families on Christmas afternoon, individuals sprawled on sofas somnolently waiting for the Queen’s speech. Maybe this is the subliminal reason that so many people come here to see the seals on Boxing Day and New Year’s Day?

The beach action is minimal: an occasional clumsy rolling over; the odd shuffle forward using flippers for traction; sporadic barking and baring of teeth between rival males. The scene looks like an aftermath of overindulgence, bodies adrift on the beach sleeping off the effects of a heavy night. Perhaps it is all that hyper-rich seal milk that explains this torpor: the effort the pups take to digest the 60%-fat fluid, the energy involved in the cows’ synthesising the milk from a diet of fish? Such extreme inactivity brings to mind an assembly of turkey dinner-replete families on Christmas afternoon, individuals sprawled on sofas somnolently waiting for the Queen’s speech. Maybe this is the subliminal reason that so many people come here to see the seals on Boxing Day and New Year’s Day? Heading inland back to the car, the lowering sun finds a gap in the clouds to paint flame red those that lie beneath. We stop for a pint in the pub and, looking out of the window observe a deer, emboldened by the burgeoning dark, casually crossing a field of sugar beet. At the car park, as the last traces of daylight evaporate, three V-shaped formations of geese fly overhead, their high, wild calls preceding the appearance of their silhouettes in the sky.

Heading inland back to the car, the lowering sun finds a gap in the clouds to paint flame red those that lie beneath. We stop for a pint in the pub and, looking out of the window observe a deer, emboldened by the burgeoning dark, casually crossing a field of sugar beet. At the car park, as the last traces of daylight evaporate, three V-shaped formations of geese fly overhead, their high, wild calls preceding the appearance of their silhouettes in the sky.