Where’s Birmingham river? Sunk.

Which river was it? Two. More or

Less.

Birmingham River Roy Fisher

The idea was to follow the Birmingham canal system north to Spaghetti Junction. I had already traversed the city by means of the Grand Union Canal a couple of years earlier, following the canal path west to arrive at the meeting of the waters at Gas Street Basin. That time I had turned left at Aston Junction but I knew that returning to that same point it would be possible to follow the Birmingham & Fazeley Canal north to reach Salford Junction directly beneath the Gravelly Hill Interchange.

Accompanying me on this venture was my friend Nigel Roberts, a fellow Bradt author devoted to Belarus and Blues (Birmingham City FC) in equal measure, who gamely agreed to come along despite our planned route veering close enough to Aston Villa’s turf to risk bringing him out in hives.

We rendezvoused in the gleaming concourse of New Street Station before making our way to Gas Street Basin by way of Victoria Square with its Queen Vic and Iron:Man statues. A notice on the ever-present temporary fencing that characterises Paradise Circus gave notice that Antony Gormley’s Iron:Man was soon to be moved to a new home. How, I wondered, might this effect the city’s sacred geometry, its unchartered leys that converged at Victoria Square? But Birmingham (motto: ‘Forward’) was always a city that messed with its past, forever rearranging the deckchairs, refurbishing the urban fabric, reinventing the wheel and then re-forging it by means of a Brummagem hammer. It always seemed a place where time not so much stood still as had a frequent lie-down, a place that lump-hammered the past into something that never quite made it to the future.

After a swift half-pint and perusal of the map at the Malt House pub opposite the geographically incongruous Sealife Centre we set off along the Birmingham & Fazeley branch towards Aston Junction. The day is atypically glorious, warm, blue-skied – peak May, the time of year you might happily be time-locked in were it at all possible. Cow parsley froths alongside the canal path, complimenting the blossoming hawthorn. Oxlips, red campion and broom compete for attention with the lurid graffiti that seems to embellish almost any available wall space. Above a lock, daubed high on a factory wall, eponymous Roof Top Vandals have left their mark in neat, bold lettering – a noteworthy combination of art and athleticism. Passing beneath the bridge that feeds railway lines into Snow Hill Station, the shimmering reflected light from the water dances like an electrocardiograph on the concrete above.

Approaching Aston, we pass the red and blue holders of the Saltley Gas Works, scene of the Battle of Saltley Gate some 46 years earlier when the fuel storage depot was mass picketed during a national miners’ strike.

A little further on, we become aware of a familiar figure atop a building – Britannia, complete with trident, excised from the back of a fifty pence piece, supersized and raised to roof level. It seems churlish not to investigate. We detour from the canal to seek out the building and head for the Lichfield Road in the wake of two teenage girls who swig beer from cans and swap yarns in rich Brummo-Caribbean argot. It is, as we thought, a pub; no longer operating as The Britannia but as The Aston Cafe. We are now perilously close to Villa Park, or Vile Park as my companion prefers to call it. It does not bother me either way – I am agnostic in such matters – but Nigel has started to sense that he is well behind enemy lines.

Returning to the canal to press on north, the Gravelly Hill Interchange aka Spaghetti Junction is already clearly visible ahead. The last house before the tangle of overlapping roadways takes over has iron railings decked in Union Jack flags – patriotism doing battle with traffic pollution. Just beyond, a defiant stand of purple lupins, garden escapes gone feral, announces our arrival at Salford Junction. Here we detour left for a short distance along the Tame Valley Canal, the curving multi-carriageway of the M6 immediately above us, articulated lorries flashing by half-seen above the barriers as they career along in compulsive centripetal motion. Above, spanning the roadways, blue signs point the way to London (M1) and The North (M6), while beside the water a navigational signpost for boats shows the various routes out of here – west to Tipton in the Black Country, north to Tamworth in north Warwickshire, back to the City Centre and Gas Street Basin (3½ miles) from whence we have come. But there are no boats today: the troubled pea-green waters beneath the Gravelly Hill Interchange fail to match most people’s criteria of what constitutes an ideal boating holiday.

Huge concrete pillars support the roads overhead – 559 in total if you were foolhardy enough to count them. The pillars bring to mind Pharaonic temples in Upper Egypt – Luxor, Karnak – although hieroglyphs and carved lotus capitals are noticeably absent. But this whole chaotic enclave of concrete, water and channelled momentum is an unintentional temple of sorts – a nexus of late capitalism; a dinosaur footprint of transport and industry, an entropic sump. The water beneath, largely deprived of direct sunlight, is an opaque soup that looks incapable of supporting anything other than menace and monsters but here and there the light sneaks in to highlight graffiti, reflect on the water and cast shapes on the wall that mutate with the sun’s arc: accidental light sculpture, the oeuvre of James Turrell; found land art.

Locked between the various roadways, the trees and bushes of a green island rise defiantly within its looping concrete confines. It is home, no doubt, to all manner of wildlife – birds, pioneering cats… foxes. A Ballardian realm of preposterous nightmares and Sci-fi imaginings, there are probably parts of the Amazon rainforest that are better explored than this singular non-place.

Satiated with the chiaroscuro experience of this interchange underworld, we return to Salford Junction and take the Grand Union Canal south through Nechells to return to the centre via a route best described as elliptical. We pass the vast entertainment complex of Star City, another latter-day temple to mammon; then an enormous recycling plant that has a conveyor belt receiving the load from a Sisyphean procession of tipper trucks, each crushed metal parcel crashing onto the hill-high mound with a shrill clatter. In uncanny juxtaposition to this unholy clamour, set back from the water is a small pond with reeds, yellow iris, water violet and water lilies – a Monet garden awaiting its artist. But for the deafening backdrop, this might be a scene in leafy Warwickshire. Indeed this whole stretch of canal, just a few minutes’ walk from Spaghetti Junction, has a disconcertingly rural feel to it. What is more, it seems almost completely deserted of people.

Reaching Garrison Lane in Bordesley we make another brief detour so that Nigel can show me the location of The Garrison, the pub whose fictional 1920s counterpart is centrepiece to the Peaky Blinders television series. There’s not a peaked cap or Shelby brother to be seen but it offers an opportunity for Nigel to fill his lungs with the right sort of air – St Andrews, Birmingham City’s home ground is only a little way up the hill.

Approaching Digbeth, we finally come upon the elusive River Rea – a shallow, sluggish channel beneath the canal viaduct. One of Birmingham’s two rivers, the other being the River Tame that it merges with close to Gravelly Hill Interchange, the Rea (pronounced ‘Ray’) spends much of its course through the city below ground out of sight. As the poet Roy Fisher claims in Birmingham River, the Rea does little to draw attention to itself: a ‘petty river’ without memory seems about right.

a slow, petty river with no memory

of an ancient

name; a river called Rea, meaning

river,

and misspelt at that.

There are places that stay in the mind long after visiting. Places that haunt the mind’s memory cache to prevail even years after having set foot there. Such places might be mountains, or rivers, or stretches of coastline; or even villages that charm and bejewel the bedrock of a singular landscape. Usually though, it is a combination of factors that constitutes the essence of such places – earth, sky, water, topography, the patina of a human occupation that beautifies rather than despoils. One such place is Lake Song-Köl in central Kyrgyzstan, the poster girl of a country that has occasionally, and not unreasonably, been described as the most beautiful in the world.

There are places that stay in the mind long after visiting. Places that haunt the mind’s memory cache to prevail even years after having set foot there. Such places might be mountains, or rivers, or stretches of coastline; or even villages that charm and bejewel the bedrock of a singular landscape. Usually though, it is a combination of factors that constitutes the essence of such places – earth, sky, water, topography, the patina of a human occupation that beautifies rather than despoils. One such place is Lake Song-Köl in central Kyrgyzstan, the poster girl of a country that has occasionally, and not unreasonably, been described as the most beautiful in the world.

Eleven miles east of the main road, six from the nearest shop (closed on the Sabbath), two miles from the open sea as the raven flies. Glen Gravir – a slender thread of houses stretching up a glen, just four more unoccupied dwellings beyond ours before the road abruptly terminates at a fence, nothing but rough wet grazing, soggy peat and unseen lochans beyond. This was our home for the week, a holiday rental in the Park (South Lochs) district of the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides.

Eleven miles east of the main road, six from the nearest shop (closed on the Sabbath), two miles from the open sea as the raven flies. Glen Gravir – a slender thread of houses stretching up a glen, just four more unoccupied dwellings beyond ours before the road abruptly terminates at a fence, nothing but rough wet grazing, soggy peat and unseen lochans beyond. This was our home for the week, a holiday rental in the Park (South Lochs) district of the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. Gravir, of which Glen Gravir is but an outpost, is large enough to feature on the map, albeit in its Gaelic form, Grabhair. The village – more a loose straggle of houses and plots – possesses a school, a fire station and a church but no shop. A road from the junction with Glenside next to the church winds its way unhurriedly downhill to the sea inlet of Loch Odhairn where there is a small jetty for boats. Some of the houses are clearly empty; others occupied by crofters and incomers, their occupants largely unseen. Others are long ruined, tenanted only by raven and opportunist rowan trees, with roofs absent and little more than chimney stacks and gable walls surviving. It is only a matter of time before the stones that have been laid to construct the walls will be indistinguishable from the native gneiss that underlies the island, surfacing above the bog here and there in outcrops like human-raised cairns. Lewisian gneiss is the oldest rock in Britain. Three billion years old, two-thirds the age of our planet, it is as hard as…well, gneiss. It is the same tough unyielding rock that five thousand years ago was painstakingly worked and positioned at the Callanish stone circle close to Lewis’s western shore; the same rock used to build the island’s churches, which occupy the same sacred sites, the same fixed points of genii loci that had been identified long before Presbyterianism or any another monotheistic faith arrived in these isolated north-western isles.

Gravir, of which Glen Gravir is but an outpost, is large enough to feature on the map, albeit in its Gaelic form, Grabhair. The village – more a loose straggle of houses and plots – possesses a school, a fire station and a church but no shop. A road from the junction with Glenside next to the church winds its way unhurriedly downhill to the sea inlet of Loch Odhairn where there is a small jetty for boats. Some of the houses are clearly empty; others occupied by crofters and incomers, their occupants largely unseen. Others are long ruined, tenanted only by raven and opportunist rowan trees, with roofs absent and little more than chimney stacks and gable walls surviving. It is only a matter of time before the stones that have been laid to construct the walls will be indistinguishable from the native gneiss that underlies the island, surfacing above the bog here and there in outcrops like human-raised cairns. Lewisian gneiss is the oldest rock in Britain. Three billion years old, two-thirds the age of our planet, it is as hard as…well, gneiss. It is the same tough unyielding rock that five thousand years ago was painstakingly worked and positioned at the Callanish stone circle close to Lewis’s western shore; the same rock used to build the island’s churches, which occupy the same sacred sites, the same fixed points of genii loci that had been identified long before Presbyterianism or any another monotheistic faith arrived in these isolated north-western isles. Ancient hard rock (as in metamorphic) may underlie Lewis, but religion is another bedrock of the island. Despite a respectable number of dwellings the only people we ever really see in the village are those who come in number on Sunday. The Hebridean Wee Free tradition guarantees a full car park on the Sabbath when smartly and soberly dressed folk from the wider locality congregate at Grabhair’s church, which, grave, grey and impressively large, is the only place of worship in this eastern part of the South Lochs district.

Ancient hard rock (as in metamorphic) may underlie Lewis, but religion is another bedrock of the island. Despite a respectable number of dwellings the only people we ever really see in the village are those who come in number on Sunday. The Hebridean Wee Free tradition guarantees a full car park on the Sabbath when smartly and soberly dressed folk from the wider locality congregate at Grabhair’s church, which, grave, grey and impressively large, is the only place of worship in this eastern part of the South Lochs district.

At the bottom of the lane beneath the hillside graveyard next to the church are a couple of recycling containers for villagers to deposit their empties and waste paper. Larger items of material consumption are left to their own devices. Rain, wind and thin acidic soil are the natural agents of decay here. Beside the roadside further up from our house lie four long-abandoned vehicles in various stages of decomposition. Engines are laid bare; bodywork and chassis, buckled and distressed, rust-coated in mimicry of the colour of lichen and autumn-faded heather. Cushions of moss have colonised the seating fabric. The rubber tyres remain surprisingly intact, the longest survivor of abandonment. Sharp-edged sedges have grown around the rotting car-carcasses as if to hide them from prying eyes, preserving some modicum of dignity as the wrecks decay into the roadside bog, all glamour expunged from a lifetime spent negotiating the island’s narrow single track roads. On Lewis, vehicles die of natural causes, not geriatric intervention.

At the bottom of the lane beneath the hillside graveyard next to the church are a couple of recycling containers for villagers to deposit their empties and waste paper. Larger items of material consumption are left to their own devices. Rain, wind and thin acidic soil are the natural agents of decay here. Beside the roadside further up from our house lie four long-abandoned vehicles in various stages of decomposition. Engines are laid bare; bodywork and chassis, buckled and distressed, rust-coated in mimicry of the colour of lichen and autumn-faded heather. Cushions of moss have colonised the seating fabric. The rubber tyres remain surprisingly intact, the longest survivor of abandonment. Sharp-edged sedges have grown around the rotting car-carcasses as if to hide them from prying eyes, preserving some modicum of dignity as the wrecks decay into the roadside bog, all glamour expunged from a lifetime spent negotiating the island’s narrow single track roads. On Lewis, vehicles die of natural causes, not geriatric intervention.

Our cottage was rented as an island base: a place to eat, rest and sleep before setting off each morning on a long drive to visit one of Lewis’s far flung corners. Happily, it feels like a home, albeit a temporary one – a domestic cocoon of cosiness with all the modest comforts we require. Its small garden is a haven. As everywhere on the island, tangerine spikes of montbretia arch like welder’s sparks from the grass. Rabbits scamper about on the lawn, colour-flushed parties of goldfinches feed on the seed heads of knapweed outside the kitchen window. Robins, wrens and blackbirds flit around the trees and shrubs that envelop the cottage – non-native plants that have adapted to the harsh weather conditions of this north-western island, softening an outlook that on a grey, wind-blown day, with a gloomy frame of mind, might be considered bleak.

Our cottage was rented as an island base: a place to eat, rest and sleep before setting off each morning on a long drive to visit one of Lewis’s far flung corners. Happily, it feels like a home, albeit a temporary one – a domestic cocoon of cosiness with all the modest comforts we require. Its small garden is a haven. As everywhere on the island, tangerine spikes of montbretia arch like welder’s sparks from the grass. Rabbits scamper about on the lawn, colour-flushed parties of goldfinches feed on the seed heads of knapweed outside the kitchen window. Robins, wrens and blackbirds flit around the trees and shrubs that envelop the cottage – non-native plants that have adapted to the harsh weather conditions of this north-western island, softening an outlook that on a grey, wind-blown day, with a gloomy frame of mind, might be considered bleak. Most days on our jaunts around the island we would see an eagle or two, golden or white-tailed, sometimes both. The majority of these sighting are in more mountainous Harris, or in that southern part of Lewis that lay close to the North Harris Hills, but on our last day on Lewis we see a white-tailed eagle fly over Orinsay, a village relatively close to where we have been staying. An hour later we spot another bird swoop along the sea loch at Cromore, a coastal village that lies a few miles to the north. It might well be the same bird. White-tailed eagles are very large and hard to miss, and their feeding range is enormous. But that is exactly how Lewis seems – enormous, almost unknowable despite its modest geographical area. A place larger than the shape on the map – a mutable landscape of rock, sky and water that does not easily lend itself to the reductionism of two-dimensional cartography.

Most days on our jaunts around the island we would see an eagle or two, golden or white-tailed, sometimes both. The majority of these sighting are in more mountainous Harris, or in that southern part of Lewis that lay close to the North Harris Hills, but on our last day on Lewis we see a white-tailed eagle fly over Orinsay, a village relatively close to where we have been staying. An hour later we spot another bird swoop along the sea loch at Cromore, a coastal village that lies a few miles to the north. It might well be the same bird. White-tailed eagles are very large and hard to miss, and their feeding range is enormous. But that is exactly how Lewis seems – enormous, almost unknowable despite its modest geographical area. A place larger than the shape on the map – a mutable landscape of rock, sky and water that does not easily lend itself to the reductionism of two-dimensional cartography.

The Saints is a small, loosely defined area of northeast Suffolk just south of the River Waveney and the Norfolk border. Effectively it is a fairly unremarkable patch of arable countryside that contains within it a baker’s dozen of small villages with names that begin or end with the name of the parish saint: St Peter South Elmham, St Michael South Elmham, St Nicholas South Elmham, St James South Elmham, St Margaret South Elmham, St Mary South Elmham, St Cross South Elmham, All Saints South Elmham, Ilketshall St Andrew, Ilketshall St Lawrence, Ilketshall St Margaret, Ilketshall St John and All Saints Mettingham. The area is bisected in its eastern fringe by the Bungay—Halesworth road that follows the course of Stone Street, a die-straight Roman construction, one of several that can still be traced on any road map of East Anglia. On the whole though the roads around here are anything but Roman in character: narrow, twisting, often bewilderingly changing direction, and marked with confusing signs (too many saints!), it is a good place to visit should you wish to humiliate your Sat Nav. John Seymour in The Companion Guide to East Anglia (1968) describes The Saints as ‘a hillbilly land into which nobody penetrates unless he has good business,’ which is perhaps hyperbolic but there is undoubtedly a feel of liminality to the area that persists to this day.

The Saints is a small, loosely defined area of northeast Suffolk just south of the River Waveney and the Norfolk border. Effectively it is a fairly unremarkable patch of arable countryside that contains within it a baker’s dozen of small villages with names that begin or end with the name of the parish saint: St Peter South Elmham, St Michael South Elmham, St Nicholas South Elmham, St James South Elmham, St Margaret South Elmham, St Mary South Elmham, St Cross South Elmham, All Saints South Elmham, Ilketshall St Andrew, Ilketshall St Lawrence, Ilketshall St Margaret, Ilketshall St John and All Saints Mettingham. The area is bisected in its eastern fringe by the Bungay—Halesworth road that follows the course of Stone Street, a die-straight Roman construction, one of several that can still be traced on any road map of East Anglia. On the whole though the roads around here are anything but Roman in character: narrow, twisting, often bewilderingly changing direction, and marked with confusing signs (too many saints!), it is a good place to visit should you wish to humiliate your Sat Nav. John Seymour in The Companion Guide to East Anglia (1968) describes The Saints as ‘a hillbilly land into which nobody penetrates unless he has good business,’ which is perhaps hyperbolic but there is undoubtedly a feel of liminality to the area that persists to this day.  The village names conjure a medieval world where saint-obsessed religion loomed large. Such a tight cluster of settlements suggests a concentration of population where parishes might eventually combine to form a town or city – with 13 villages and the same number of churches (eleven of which are extant), there were more churches here than in all of Cambridge. But The Saints never coalesced to become a medieval city – none of the villages had a port, defensive structure or even significant market to its credit and consequently the area would slowly slip into obscurity as the medieval era played out and other East Anglia towns and cities – Cambridge, Bury St Edmunds, Ipswich and, of course, Norwich – took the baton of influence and power.

The village names conjure a medieval world where saint-obsessed religion loomed large. Such a tight cluster of settlements suggests a concentration of population where parishes might eventually combine to form a town or city – with 13 villages and the same number of churches (eleven of which are extant), there were more churches here than in all of Cambridge. But The Saints never coalesced to become a medieval city – none of the villages had a port, defensive structure or even significant market to its credit and consequently the area would slowly slip into obscurity as the medieval era played out and other East Anglia towns and cities – Cambridge, Bury St Edmunds, Ipswich and, of course, Norwich – took the baton of influence and power.  It was not always so: one of the villages in particular held great significance in its day. The land covered by the South Elmham parishes was once owned by Almar, Bishop of East Anglia and the late Saxon Bishops of Norwich had a summer palace here at St Cross, now South Elmham Hall. The most intriguing of the churches lies within the same parish. It is not in any way complete but a ruin framed by woodland a good half mile from the nearest road. South Elmham Minster, although probably never a minster proper, is veiled in mystery regarding its origins but its appeal owes as much to its half-hidden location as it does to its obscure history. South Elmham may have once been the seat of the second East Anglian bishopric (the first was in Dunwich, the sea-ravaged village on the Suffolk coast), although North Elmham in Norfolk seems a more likely contender. Whatever the ruin’s original function – a private chapel for Herbert de Losinga, Norwich’s first bishop, is another possibility, or it may even be that a second bishopric was founded here – the church in the wood just south of South Elmham Hall dates back at least to the 11th century. It is probably older in origin – a ninth-century gravestone has been unearthed in its foundations. The site itself is undoubtedly of greater antiquity: a continuation of an earlier Anglo-Saxon presence that occupied the same moated site, which, earlier still, was home to a Roman temple and perhaps, even earlier, a pagan holy place.

It was not always so: one of the villages in particular held great significance in its day. The land covered by the South Elmham parishes was once owned by Almar, Bishop of East Anglia and the late Saxon Bishops of Norwich had a summer palace here at St Cross, now South Elmham Hall. The most intriguing of the churches lies within the same parish. It is not in any way complete but a ruin framed by woodland a good half mile from the nearest road. South Elmham Minster, although probably never a minster proper, is veiled in mystery regarding its origins but its appeal owes as much to its half-hidden location as it does to its obscure history. South Elmham may have once been the seat of the second East Anglian bishopric (the first was in Dunwich, the sea-ravaged village on the Suffolk coast), although North Elmham in Norfolk seems a more likely contender. Whatever the ruin’s original function – a private chapel for Herbert de Losinga, Norwich’s first bishop, is another possibility, or it may even be that a second bishopric was founded here – the church in the wood just south of South Elmham Hall dates back at least to the 11th century. It is probably older in origin – a ninth-century gravestone has been unearthed in its foundations. The site itself is undoubtedly of greater antiquity: a continuation of an earlier Anglo-Saxon presence that occupied the same moated site, which, earlier still, was home to a Roman temple and perhaps, even earlier, a pagan holy place.  We leave the car in a muddy parking area alongside another vehicle and a dumped piece of agricultural machinery. Nearby stands a weather-beaten trestle table that suggests that this once might have served as a designated picnic spot. Now half-submerged in grass and thistles, the table did not look as if any sandwich boxes had been opened on it for some time. Things have changed here a little in recent years: the permissive footpaths that once threaded through the South Elmham estate are no longer available for the public, and the hall itself has been re-purposed for use as a wedding and conference venue. At least the minster was still accessible by means of a green lane and a public footpath across fields.

We leave the car in a muddy parking area alongside another vehicle and a dumped piece of agricultural machinery. Nearby stands a weather-beaten trestle table that suggests that this once might have served as a designated picnic spot. Now half-submerged in grass and thistles, the table did not look as if any sandwich boxes had been opened on it for some time. Things have changed here a little in recent years: the permissive footpaths that once threaded through the South Elmham estate are no longer available for the public, and the hall itself has been re-purposed for use as a wedding and conference venue. At least the minster was still accessible by means of a green lane and a public footpath across fields.  The green lane is flanked by mature hedges frothed white with blackthorn blossom. Reaching its bottom end we turn left to follow a footpath alongside a stream, a minor tributary of the River Waveney; strange hollowed-out hornbeams measure out its bank. Soon we come to the copse that contains the ruin, a rusty gate gives admission across a partial moat and raised bank into what can only be described as a woodland glade. The ancient flint walls of the church stand central, striated by the shadow of hornbeams still leafless in late March. There is no sign of a roof but the weathered walls of the nave are clear in outline, as is the single entrance to the west. On the ground, last year’s fallen leaves provide a soft bronze carpet that is mostly devoid of ground plants.

The green lane is flanked by mature hedges frothed white with blackthorn blossom. Reaching its bottom end we turn left to follow a footpath alongside a stream, a minor tributary of the River Waveney; strange hollowed-out hornbeams measure out its bank. Soon we come to the copse that contains the ruin, a rusty gate gives admission across a partial moat and raised bank into what can only be described as a woodland glade. The ancient flint walls of the church stand central, striated by the shadow of hornbeams still leafless in late March. There is no sign of a roof but the weathered walls of the nave are clear in outline, as is the single entrance to the west. On the ground, last year’s fallen leaves provide a soft bronze carpet that is mostly devoid of ground plants.  Church or not, there is a timelessness to this place in the woods. And a strong sense of genius loci, the sort of thing that put the wind up the Romans with their straight lines and four-square militaristic outlook. I wander off to explore the bank to the west and discover the opening of a badger sett that looks to be newly excavated. Without much expectation, I rummage though the spoil musing that there might just be the remotest of chances that, burrowing deep beneath the mound, the animals have thrown up some treasure long buried in the soil below: an Anglo-Saxon torc, a Roman coin perhaps? I would even settle for a rusty button, but nothing. No matter, the mystery of the place is enough for now. We leave the bosky comfort of the site and retrace our steps along the beck and green lane back to the car. The other car has gone – we never did see its occupants.

Church or not, there is a timelessness to this place in the woods. And a strong sense of genius loci, the sort of thing that put the wind up the Romans with their straight lines and four-square militaristic outlook. I wander off to explore the bank to the west and discover the opening of a badger sett that looks to be newly excavated. Without much expectation, I rummage though the spoil musing that there might just be the remotest of chances that, burrowing deep beneath the mound, the animals have thrown up some treasure long buried in the soil below: an Anglo-Saxon torc, a Roman coin perhaps? I would even settle for a rusty button, but nothing. No matter, the mystery of the place is enough for now. We leave the bosky comfort of the site and retrace our steps along the beck and green lane back to the car. The other car has gone – we never did see its occupants.

Today is St Patrick’s Day and March 17 is the supposed date of the 5th-century missionary’s death. Patrick was the forerunner of many early missionaries who came to Irish shores to preach Christianity, the island more receptive to new ideas about religion than its larger neighbour to the east across the Irish Sea. Consequently Ireland abounds with relics and ruins of early Christianity, sometimes in the most improbable of places.

Today is St Patrick’s Day and March 17 is the supposed date of the 5th-century missionary’s death. Patrick was the forerunner of many early missionaries who came to Irish shores to preach Christianity, the island more receptive to new ideas about religion than its larger neighbour to the east across the Irish Sea. Consequently Ireland abounds with relics and ruins of early Christianity, sometimes in the most improbable of places. Sailing around Ireland’s southwest coast, skirting the peninsulas that splay out from the Kerry coast, the two islands of the Skelligs come into view after rounding Bolus Head at the end of the Inveragh Peninsula. Both islands are sheer, with sharp-finned summits that resemble inverted boat keels. The smaller of the two appears largely white at first but increasing proximity reveals that the albino effect is down to a combination of nesting gannets and guano. The acrid tang of ammonia on the breeze and distant cacophony announce the presence of the birds well before the identity of any individual can be confirmed by binoculars.

Sailing around Ireland’s southwest coast, skirting the peninsulas that splay out from the Kerry coast, the two islands of the Skelligs come into view after rounding Bolus Head at the end of the Inveragh Peninsula. Both islands are sheer, with sharp-finned summits that resemble inverted boat keels. The smaller of the two appears largely white at first but increasing proximity reveals that the albino effect is down to a combination of nesting gannets and guano. The acrid tang of ammonia on the breeze and distant cacophony announce the presence of the birds well before the identity of any individual can be confirmed by binoculars. As the boat draws closer, the sheer volume of birds – gannets, fulmars, puffins, terns – becomes plain to see. With something like 70,000 birds, Little Skellig is the second largest gannet colony in the world. But on the larger island of Skellig Michael, although seabirds abound here too, there is also the suggestion of a human presence, albeit an historic one. High up in the rocks, small stone structures can be discerned: rounded domes that are clearly man-made and which soften the jagged silhouette of the island’s summit. These are beehive cells, the dry-stone oratories favoured by early Irish monks for their meditation. Sitting aloft the island on a high terrace, commanding a panoramic view over the Atlantic Ocean in one direction and the fractal Kerry coast in the other, these simple stone cells came without windows – the business was one of prayer and meditation not horizon-gazing. Such isolation was necessary for reasons of both safety and spirituality. And Skellig Michael was the acme of isolation. In the early Christian milieu the Skellig Islands, facing the seemingly limitless Atlantic off the southwest coast of Ireland, were more than merely remote: they were at the very edge of the known world.

As the boat draws closer, the sheer volume of birds – gannets, fulmars, puffins, terns – becomes plain to see. With something like 70,000 birds, Little Skellig is the second largest gannet colony in the world. But on the larger island of Skellig Michael, although seabirds abound here too, there is also the suggestion of a human presence, albeit an historic one. High up in the rocks, small stone structures can be discerned: rounded domes that are clearly man-made and which soften the jagged silhouette of the island’s summit. These are beehive cells, the dry-stone oratories favoured by early Irish monks for their meditation. Sitting aloft the island on a high terrace, commanding a panoramic view over the Atlantic Ocean in one direction and the fractal Kerry coast in the other, these simple stone cells came without windows – the business was one of prayer and meditation not horizon-gazing. Such isolation was necessary for reasons of both safety and spirituality. And Skellig Michael was the acme of isolation. In the early Christian milieu the Skellig Islands, facing the seemingly limitless Atlantic off the southwest coast of Ireland, were more than merely remote: they were at the very edge of the known world. The island’s monastic site is infused with mystery, as all good ruins are, but is thought to have been established in the 6th century by Saint Fionán. Consisting of six beehive cells, two oratories and a later medieval church, the site occupies a stone terrace 600 feet above the swirling green waters of the sea below.

The island’s monastic site is infused with mystery, as all good ruins are, but is thought to have been established in the 6th century by Saint Fionán. Consisting of six beehive cells, two oratories and a later medieval church, the site occupies a stone terrace 600 feet above the swirling green waters of the sea below. Skirting Skellig Michael, a landing stage with a helicopter pad comes into view. A vertiginous path of stone steps leads up towards the beehive huts close to the island’s mountain-like summit. We do not disembark. Instead we keep sailing, bound for a safer harbour in Glengarriff in County Cork. No matter, the sight of the rocks, the winding, climbing path and the austere cells on the terrace at the top is already imprinted on our memory.

Skirting Skellig Michael, a landing stage with a helicopter pad comes into view. A vertiginous path of stone steps leads up towards the beehive huts close to the island’s mountain-like summit. We do not disembark. Instead we keep sailing, bound for a safer harbour in Glengarriff in County Cork. No matter, the sight of the rocks, the winding, climbing path and the austere cells on the terrace at the top is already imprinted on our memory. Without doubt this was a life of supreme hardship: the isolation, the relentless diet of fish and seabird eggs, the ever-battering wind and salt-spray. Such was the isolation, and so extreme the privations of this beatific pursuit, that one might assume that the monks would have been left in peace to practice their calling. This was not to be. Viking raiders arrived here in the early 9th century and took the trouble to land, scale the island’s heights and attack the monks. For most of us it is probably difficult to comprehend the blind-rage fury of the raiders, the wrath invoked in them by pious upstarts with their new Christian God. Easier perhaps is to imagine the dread that must have been felt by the monks as the Vikings approached their spiritual eyrie.

Without doubt this was a life of supreme hardship: the isolation, the relentless diet of fish and seabird eggs, the ever-battering wind and salt-spray. Such was the isolation, and so extreme the privations of this beatific pursuit, that one might assume that the monks would have been left in peace to practice their calling. This was not to be. Viking raiders arrived here in the early 9th century and took the trouble to land, scale the island’s heights and attack the monks. For most of us it is probably difficult to comprehend the blind-rage fury of the raiders, the wrath invoked in them by pious upstarts with their new Christian God. Easier perhaps is to imagine the dread that must have been felt by the monks as the Vikings approached their spiritual eyrie.

If trees could only speak. If they had some semblance of sentience and memory, and a means of communication, what would they tell us? Ancient trees – or at least those we suspect to be very old – are usually described in terms of human history. Perhaps as humans it is hubris that requires us to define them in this way but the fact is that by and large they tend to outlive us: many lofty oaks that stand today were already reaching for the sky when the Industrial Revolution changed the face of the land over two centuries ago. This linkage of history and old trees has resulted in some colourful local history. The story of the future King Charles II hiding from parliamentarian troops up a pollarded oak tree in Boscobel, Shropshire carried sufficient potency for the original tree to have been eventually killed by souvenir hunters excessively lopping of its branches as keepsakes. Undoubtedly the stuff of legend, Royal Oak ended up becoming the third commonest pub name in England. A long-established folk belief also tells of the Glastonbury Thorn, the tree which is said to have grown from the staff of Joseph of Arithmathea whom legend has it once visited Glastonbury with the Holy Grail. What was considered to be the original tree perished during the English Civil War, chopped down and burned by Cromwell’s troops who clearly held a grudge against any tree that came with spiritual associations or historical attitude.

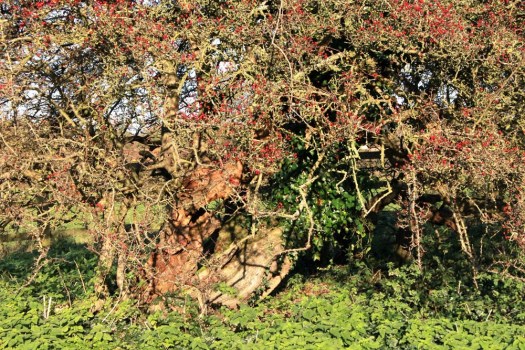

If trees could only speak. If they had some semblance of sentience and memory, and a means of communication, what would they tell us? Ancient trees – or at least those we suspect to be very old – are usually described in terms of human history. Perhaps as humans it is hubris that requires us to define them in this way but the fact is that by and large they tend to outlive us: many lofty oaks that stand today were already reaching for the sky when the Industrial Revolution changed the face of the land over two centuries ago. This linkage of history and old trees has resulted in some colourful local history. The story of the future King Charles II hiding from parliamentarian troops up a pollarded oak tree in Boscobel, Shropshire carried sufficient potency for the original tree to have been eventually killed by souvenir hunters excessively lopping of its branches as keepsakes. Undoubtedly the stuff of legend, Royal Oak ended up becoming the third commonest pub name in England. A long-established folk belief also tells of the Glastonbury Thorn, the tree which is said to have grown from the staff of Joseph of Arithmathea whom legend has it once visited Glastonbury with the Holy Grail. What was considered to be the original tree perished during the English Civil War, chopped down and burned by Cromwell’s troops who clearly held a grudge against any tree that came with spiritual associations or historical attitude. There is an ancient thorn in Norfolk that is sometimes connected with the same Joseph of Arithmathea myth. Hethel Old Thorn can be found along narrow lanes amidst unremarkable farming country 10 miles south of Norwich. Close to the better known

There is an ancient thorn in Norfolk that is sometimes connected with the same Joseph of Arithmathea myth. Hethel Old Thorn can be found along narrow lanes amidst unremarkable farming country 10 miles south of Norwich. Close to the better known  At an estimated 700 years old this is thought to be the oldest specimen of Crataegus monogyna in the UK. Like the nearby Kett’s Oak, the thorn was thought to be a meeting place for the rebels during

At an estimated 700 years old this is thought to be the oldest specimen of Crataegus monogyna in the UK. Like the nearby Kett’s Oak, the thorn was thought to be a meeting place for the rebels during