Of all the footpaths and byways that criss-cross our ancient landscape probably the most enigmatic are those that cannot be mapped because of their very impermanence. Such routes can only be defined by their start and end points rather than the space that lies in between. These conduits of human movement are impermanent in the sense that their course is forever obliged to change with the whims of nature. What is fixed is the historical notion of the route rather than the precise territory that has been traversed. Like shipping routes that must studiously avoid rocks but which have a freer rein in safe channels, footways across tidal estuaries are fluid and everchanging. One celebrated historic route is that which crosses Morecambe Bay on the south Cumbrian coast.

Of all the footpaths and byways that criss-cross our ancient landscape probably the most enigmatic are those that cannot be mapped because of their very impermanence. Such routes can only be defined by their start and end points rather than the space that lies in between. These conduits of human movement are impermanent in the sense that their course is forever obliged to change with the whims of nature. What is fixed is the historical notion of the route rather than the precise territory that has been traversed. Like shipping routes that must studiously avoid rocks but which have a freer rein in safe channels, footways across tidal estuaries are fluid and everchanging. One celebrated historic route is that which crosses Morecambe Bay on the south Cumbrian coast.

Men and women have been crossing Morecambe Bay for centuries, millennia even, but the passage has always been fraught with the danger of quicksand and fast-moving incoming tides. The tragedy that befell a group Chinese cockle diggers stranded here a decade ago is still fresh in the national psyche. Caught by the perfidious tide, abandoned by unscrupulous gangmasters, the poor migrants that perished here were caught out by both nature and the greed and indifference of their exploiters.

Men and women have been crossing Morecambe Bay for centuries, millennia even, but the passage has always been fraught with the danger of quicksand and fast-moving incoming tides. The tragedy that befell a group Chinese cockle diggers stranded here a decade ago is still fresh in the national psyche. Caught by the perfidious tide, abandoned by unscrupulous gangmasters, the poor migrants that perished here were caught out by both nature and the greed and indifference of their exploiters.

While Morecambe Bay’s dangers are apparent enough, there is one man who, given time, can always find a way across between the south and north shores of the bay. Cedric Robinson MBE is the official ‘Queen’s Guide to the Sands of Morecambe Bay’ and receives the princely sum of £15 annually from the Crown (and a virtually rent-free cottage) for performing this duty. Formerly a fisherman and farmer, Cedric is the 25th custodian of the the title having performed the role since 1963. The first official guide was appointed by the Duchy of Lancaster back in the mid 16th century. Prior to this, it was the monks of Cartmel Priory who escorted travellers across the sands. No doubt little has changed in the way that the guides read the landscape – assessing the movement of the sands, the shift of the channels, the whereabouts of treacherous quicksand and the height of the river water. In a grudging nod to modernity, Cedric also has a tractor at his disposal.

The weather forecast for our crossing from Arnside to Kents Bank was anything but auspicious, with predictions of heavy rain and the threat of the summer storms that had already tormented the south of England making an unwelcome appearance. Come the day though, there seemed to be nothing worse than light drizzle and low cloud.

Something of the order of one hundred people had assembled at the jetty at Arnside for the 11am start across the bay. Cedric appeared on cue to blow his whistle and lead a colourfully (yet sensibly) clad crocodile of hikers, geocachers, dog-walkers and other outdoorsy types along the high street and past a caravan site before venturing out across the estuary. Leaving dry land behind, the group soon becomes an ambulant community, a walking-talking organism worming its way west across the sands. Crossing is exhilarating rather than a solemn trudge and the next three hours pass quickly as we walk briskly over rippled sand and wade through knee-high through channels of the River Kent, its fresh water surprisingly warm.

It all seems surprisingly straightfoward, even crossing the river channels where there is a distinct undertow. Such ease of passage is thanks to Cedric who has already been out the previous day weighing up the options and marking the ever-changing route with laurel branches (‘brobs’, cut close to Cedric’s Kents Bank home at Guides Farm) that he has wedged into deep holes crow-barred into the mud. The markers are good for the next couple of days but when Cedric next takes a group out in a fortnight’s time he will need to do the pathfinding and route-marking all over again – nothing is permanent here. In Morecambe Bay the fluidity of time is all-apparent.

Halfway across, the light rain eases and the sun appears, albeit dimly like a ghostly face through frosted glass. In the distance, a tractor and trailer driven by Cedric’s assistant can be seen on the bank of the River Kent, our first serious wade. The shoreline now seems a distant and untrustworthy illusion, the glimpses of Morecambe seen to the southeast, a phantasmagorical will-o’-the-wisp beyond a hazy threshold to another world. Once across the second of the deeper channels we wait while Cedric does some last minute route-finding, walking some distance towards the houses of Grange-over-Sands on the north shore before returning to give us the all-clear.

Halfway across, the light rain eases and the sun appears, albeit dimly like a ghostly face through frosted glass. In the distance, a tractor and trailer driven by Cedric’s assistant can be seen on the bank of the River Kent, our first serious wade. The shoreline now seems a distant and untrustworthy illusion, the glimpses of Morecambe seen to the southeast, a phantasmagorical will-o’-the-wisp beyond a hazy threshold to another world. Once across the second of the deeper channels we wait while Cedric does some last minute route-finding, walking some distance towards the houses of Grange-over-Sands on the north shore before returning to give us the all-clear.

Just before we reach the sheep-grazed marshes that fringe the shoreline, there is a moment of high drama as an area of sand the size of a car wobbles alarmingly like a jelly fish to warn of its danger: unstable quicksand with water beneath that could swallow a horse (indeed, Cedric has actually witnessed such a thing). Even the most maverick among us need no reminding to skirt this and keep moving until we are on firmer ground. A little further on and the scattered buildings of the shoreline assert themselves from behind the trees and we find ourselves climbing up to the platform of Kents Bank railway station. A southbound train is due and after bidding Cedric farewell (and purchasing a ‘Certificate of Crossing’ and a signed copy of his Time and Tide book) we climb on board for the two-stop, ten-minute journey back to Arnside. The train itself is bound for Manchester Airport, an altogether more obvious starting point for journeys to other phantasmagorical worlds that lie beyond the threshold of our imagination.

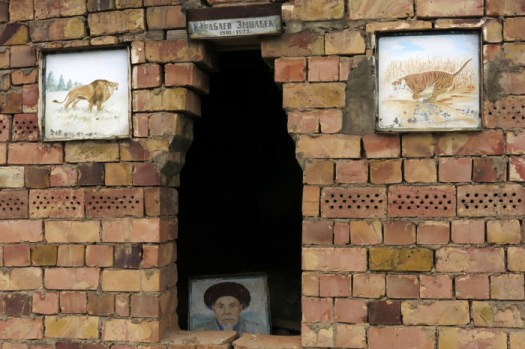

You see them everywhere in Kyrgyzstan. From afar they resemble hillside villages of mud-brick dwellings but a closer look reveals them to be cemeteries. Usually located a little way outside a village, sometimes on top of a low bluff, they are often more impressive than the villages they serve. With a mixture of mud-brick, shrine-like tombs, gravestones with etched images of the deceased, and Islamic crescent moons intermixed with communist five-pointed stars, they represent an odd amalgam of funerary styles. What makes them unmistakably Kyrgyz, though, are the large, wrought-iron, yurt structures that mark many of the graves.

You see them everywhere in Kyrgyzstan. From afar they resemble hillside villages of mud-brick dwellings but a closer look reveals them to be cemeteries. Usually located a little way outside a village, sometimes on top of a low bluff, they are often more impressive than the villages they serve. With a mixture of mud-brick, shrine-like tombs, gravestones with etched images of the deceased, and Islamic crescent moons intermixed with communist five-pointed stars, they represent an odd amalgam of funerary styles. What makes them unmistakably Kyrgyz, though, are the large, wrought-iron, yurt structures that mark many of the graves. In Kyrgyz graveyards disparate traditions – shamanistic, Islamic, communist – intermingle freely. Gently crumbling as their mud-brick mausoleums slowly decay back into the earth, such cemeteries can be seen far and wide in this central Asian country. Some of the finest are those that can be seen in villages along the Suusamyr Valley in Chui Province. The photos here were taken in two villages in this isolated valley – Kyzyl-Oi and Suusamayr.

In Kyrgyz graveyards disparate traditions – shamanistic, Islamic, communist – intermingle freely. Gently crumbling as their mud-brick mausoleums slowly decay back into the earth, such cemeteries can be seen far and wide in this central Asian country. Some of the finest are those that can be seen in villages along the Suusamyr Valley in Chui Province. The photos here were taken in two villages in this isolated valley – Kyzyl-Oi and Suusamayr.

![2029[1]](https://eastofelveden.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/20291.jpg?w=525&h=799)

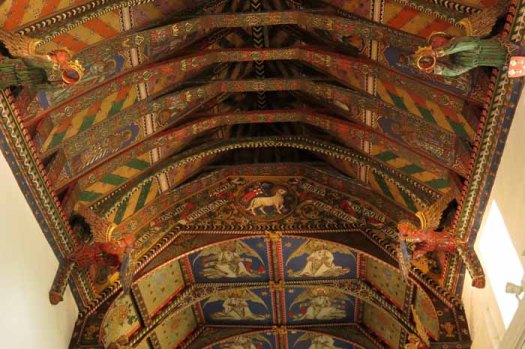

A little way south of Norwich, standing atop what counts for a hill in these parts, is a tiny roundtower church nestled amidst trees. All Saints Church stands above the small village of Keswick in a crumpled corduroy landscape of wintry ploughed fields. Like most of the territory of this urban fringe, the church lies within the acoustic shadow of the city’s southern bypass and the dull thrum of traffic melds with the chatter of birds in the trees and hedgerows – mostly finches, tits and blackbirds at this time of year. Across the valley, a thread of pylons leads inexorably north towards Norwich where they will deliver electricity to power the city’s PlayStations, fridge-freezers and TiVo boxes.

A little way south of Norwich, standing atop what counts for a hill in these parts, is a tiny roundtower church nestled amidst trees. All Saints Church stands above the small village of Keswick in a crumpled corduroy landscape of wintry ploughed fields. Like most of the territory of this urban fringe, the church lies within the acoustic shadow of the city’s southern bypass and the dull thrum of traffic melds with the chatter of birds in the trees and hedgerows – mostly finches, tits and blackbirds at this time of year. Across the valley, a thread of pylons leads inexorably north towards Norwich where they will deliver electricity to power the city’s PlayStations, fridge-freezers and TiVo boxes.