I don’t quite know what it is but whenever I have come across an old Lenin statue anywhere in the territories of the old Soviet Union I have usually not been able to resist taking a photograph. It may be it purely a matter of posterity – these things will not be there for ever. But perhaps it for other reasons – vague nostalgia for something I never had the opportunity to experience, or a sneaking regard for an idealistic yet flawed political system that had such indomitable self-belief? Another part of me acknowledges that I am drawn towards old Soviet statuary in the same way I am attracted to photogenic ruins: as revolutionary ghosts manifest in stone and concrete that serve as repositories for the recent past.

The countries of the former Soviet Union have widely differing attitudes to displaying representations of their erstwhile leader Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. The new Baltic countries and those of the Caucasus region, keen to sever any lasting connections with the USSR, tend to shun them completely – most of the old statuary has long been toppled and reduced to rubble or hardcore for roads. In a few cases, like the irony-heavy Grutas Park in Lithuania, the statues have been collected together and repurposed to make a joke of the past by creating a sort of Soviet-era theme park. This comes complete with statues, barbed wire, military music and canteens that serves ‘Soviet-style’ food – dishes that feature cabbage, beetroot and, of course, vodka. Such a move is motivated by nostalgia to some extent, but it is also undoubtedly partly taking the piss.

The countries of the former Soviet Union have widely differing attitudes to displaying representations of their erstwhile leader Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. The new Baltic countries and those of the Caucasus region, keen to sever any lasting connections with the USSR, tend to shun them completely – most of the old statuary has long been toppled and reduced to rubble or hardcore for roads. In a few cases, like the irony-heavy Grutas Park in Lithuania, the statues have been collected together and repurposed to make a joke of the past by creating a sort of Soviet-era theme park. This comes complete with statues, barbed wire, military music and canteens that serves ‘Soviet-style’ food – dishes that feature cabbage, beetroot and, of course, vodka. Such a move is motivated by nostalgia to some extent, but it is also undoubtedly partly taking the piss.

Ukraine, which once had an impressive number of Lenin statues, has got rid of up to 500 of these over the past couple of years, an ideological casualty of the civil war and perceived Russian aggression in that divided land. Currently many still remain in place but President Petro Poroshenko has recently signed a bill setting a six-month deadline for the removal of the country’s remaining communist monuments and so their days are probably numbered – in the pro-European west of the country at least.

Ukraine, which once had an impressive number of Lenin statues, has got rid of up to 500 of these over the past couple of years, an ideological casualty of the civil war and perceived Russian aggression in that divided land. Currently many still remain in place but President Petro Poroshenko has recently signed a bill setting a six-month deadline for the removal of the country’s remaining communist monuments and so their days are probably numbered – in the pro-European west of the country at least.

Elsewhere, where Soviet-era murals are attached to buildings or just too cumbersome to remove wholesale, the offending revolutionary faces are simply scratched away. I once saw a hillside in Uzbekistan where a Lenin-shaped ghost image was left where a giant face had been erased from the landscape. Once lovingly marked out in stone, the image of the revolutionary leader was no longer needed – or indeed desired – in a newly independent country presided over by a self-elected president-for-life. I have seen much the same sort of thing in Georgia – murals of Soviet period scientific achievements in which Lenin’s face has been clumsily redacted by means of a chisel. Curiously, local boy Stalin – a far more murderous character than Lenin ever was – is still revered in some circles in that country. A museum to the ‘Man of Steel’ – more a shrine of very dubious taste – still stands at his hometown of Gori together with a statue that used to have pride of place in the town’s main square.

Elsewhere, where Soviet-era murals are attached to buildings or just too cumbersome to remove wholesale, the offending revolutionary faces are simply scratched away. I once saw a hillside in Uzbekistan where a Lenin-shaped ghost image was left where a giant face had been erased from the landscape. Once lovingly marked out in stone, the image of the revolutionary leader was no longer needed – or indeed desired – in a newly independent country presided over by a self-elected president-for-life. I have seen much the same sort of thing in Georgia – murals of Soviet period scientific achievements in which Lenin’s face has been clumsily redacted by means of a chisel. Curiously, local boy Stalin – a far more murderous character than Lenin ever was – is still revered in some circles in that country. A museum to the ‘Man of Steel’ – more a shrine of very dubious taste – still stands at his hometown of Gori together with a statue that used to have pride of place in the town’s main square.

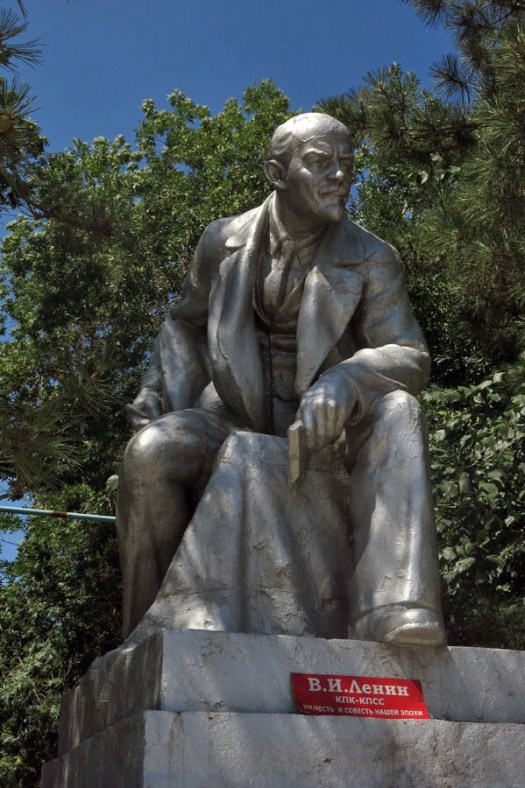

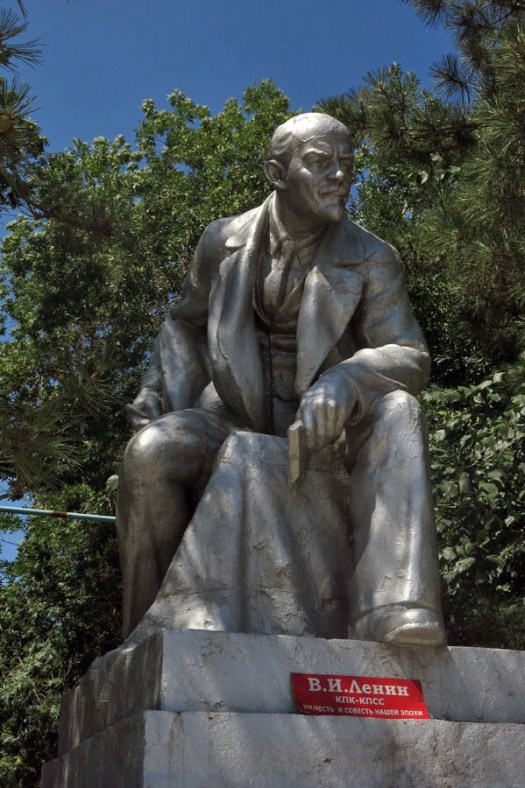

Russia has long condemned Stalin’s brutal excesses but his predecessor Lenin can still to be seen in more or less every town and city the length and breadth of the land. The same can also be said for Belarus, Russia’s closest ally in Europe. Kyrgyzstan – the Central Asian country I know best – is much the same, the only only place in Central Asia where it would appear that the recent Soviet past is not thoroughly scorned. Weather-beaten statues and busts of Lenin can still be seen in most towns in the country, although these are now slowly being usurped by shiny heroic representations of national heroes like Manas and Kurmanjan Datka.

Photographs from top to bottom (all ©Laurence Mitchell)

Lenin and bust in Soviet sculpture park, Moscow, Russia

Lenin waving at civic buildings, Yekaterinberg, Russia

Lenin in taxi-hailing mode, Irkutsk, Siberia, Russia

Nonchalant Lenin, Pskov, Russia

Redacated Lenin face on Soviet space travel memorial, Akhaltsikhe, Georgia

Lenin and friends, Russian flea market, Tbilisi, Georgia

Dynamic ‘caped crusader’ Lenin, Tirasapol, Transdniestr

Lenin the theatrical performer (note the redacted face on plinth), Kochkor, Kyrgyzstan

Lenin the thinker, Jalal-Abad, Kyrgyzstan

Lenin points out the lofty Ala-Too mountains beyond the city (not any more though, he’s been moved and now faces the other way), Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

Stoic upright Lenin with Kyrgyzstan flag, Chaek, Kyrgyzstan

My feature on walking part of the Kumano Kodō pilgrimage trail in Japan will be published in a few days time in Elsewhere journal. Elsewhere is a Berlin-based print journal, published twice a year, dedicated to writing and visual art that explores the idea of place in all its forms, whether city neighbourhoods or island communities, heartlands or borderlands, the world we see before us or landscapes of the imagination.

My feature on walking part of the Kumano Kodō pilgrimage trail in Japan will be published in a few days time in Elsewhere journal. Elsewhere is a Berlin-based print journal, published twice a year, dedicated to writing and visual art that explores the idea of place in all its forms, whether city neighbourhoods or island communities, heartlands or borderlands, the world we see before us or landscapes of the imagination.

One way of looking at this evocative, if mildly disturbing, place is as a hidden enclave populated with the ghosts of colonialism. Situated right in the middle of Kolkata, tucked away purdah-like from the mayhem of the city streets, the Park Street Cemetery seems like another world. It really is another world: one in which time has coalesced to leave a thick patina on the colonnades and obelisks that commemorate the colonists who created this tropical city in their own image. The colonials mostly died young – easy victims of the disease-ridden, febrile climate that characterised this distant outpost of the East India Company. In true Victorian manner, those who were unfortunate enough to die young and never be able to return to their temperate homeland were interred here in magnificent mausoleums among lush, very un-British vegetation – a tropical Highgate transposed a quarter-way round the world. The cemetery is reputed to be the largest Old World 19th-century Christian graveyard outside Europe. It is also one of the earliest non-church cemeteries, dating from the 1767 and built like much of Kolkata/Calcutta on low, marshy ground. The overall effect is one of Victorian Gothic, although there are also some notable flourishes of Indo-Saracenic vernacular that reflect the influence of Hindu temple architecture.

One way of looking at this evocative, if mildly disturbing, place is as a hidden enclave populated with the ghosts of colonialism. Situated right in the middle of Kolkata, tucked away purdah-like from the mayhem of the city streets, the Park Street Cemetery seems like another world. It really is another world: one in which time has coalesced to leave a thick patina on the colonnades and obelisks that commemorate the colonists who created this tropical city in their own image. The colonials mostly died young – easy victims of the disease-ridden, febrile climate that characterised this distant outpost of the East India Company. In true Victorian manner, those who were unfortunate enough to die young and never be able to return to their temperate homeland were interred here in magnificent mausoleums among lush, very un-British vegetation – a tropical Highgate transposed a quarter-way round the world. The cemetery is reputed to be the largest Old World 19th-century Christian graveyard outside Europe. It is also one of the earliest non-church cemeteries, dating from the 1767 and built like much of Kolkata/Calcutta on low, marshy ground. The overall effect is one of Victorian Gothic, although there are also some notable flourishes of Indo-Saracenic vernacular that reflect the influence of Hindu temple architecture.  Arriving at the gatehouse my name is recorded in a ledger by a lugubrious guard, an action that in itself carries the hint of entering some sort of forbidden zone, a place where the living are only tolerated and should not outstay their welcome. The cemetery seems largely deserted of visitors, although I do inadvertently stumble across a spot of surreptitious man-on-man action taking place in the deep shade of one of the tombs. Despite the funerary setting, there is nothing occult at work here, and I conclude that the young men are simply taking advantage of the privacy offered by the cemetery in this most crowded of all India’s overflowing mega cities. There are signs prohibiting ‘committing nuisance’ attached to some of the trees and I wonder if this is a warning against this sort of clandestine liaison, although in India the expression is usually a euphemism for public urination.

Arriving at the gatehouse my name is recorded in a ledger by a lugubrious guard, an action that in itself carries the hint of entering some sort of forbidden zone, a place where the living are only tolerated and should not outstay their welcome. The cemetery seems largely deserted of visitors, although I do inadvertently stumble across a spot of surreptitious man-on-man action taking place in the deep shade of one of the tombs. Despite the funerary setting, there is nothing occult at work here, and I conclude that the young men are simply taking advantage of the privacy offered by the cemetery in this most crowded of all India’s overflowing mega cities. There are signs prohibiting ‘committing nuisance’ attached to some of the trees and I wonder if this is a warning against this sort of clandestine liaison, although in India the expression is usually a euphemism for public urination.  There are, of course, those who take full advantage of the cemetery’s concentrated occult power – fakirs who use it for training apprentices by making them spend the night here alone, an experience that could never be a comfortable one however much one was inured to the idea of djinns being hyperactive after dark. Even for hard-nosed rationalists, the sense of the numinous here is quite tangible, and the cemetery is without doubt a thoroughly spooky place. This is true even in broad daylight when the taxi horns and traffic thrum from the manic thoroughfare of Mother Teresa Sarani (formerly Park Street; before that, Burial Ground Road) cuts through the trees to provide a background drone for the tuneless squawks of the urban crows and parakeets that loiter here.

There are, of course, those who take full advantage of the cemetery’s concentrated occult power – fakirs who use it for training apprentices by making them spend the night here alone, an experience that could never be a comfortable one however much one was inured to the idea of djinns being hyperactive after dark. Even for hard-nosed rationalists, the sense of the numinous here is quite tangible, and the cemetery is without doubt a thoroughly spooky place. This is true even in broad daylight when the taxi horns and traffic thrum from the manic thoroughfare of Mother Teresa Sarani (formerly Park Street; before that, Burial Ground Road) cuts through the trees to provide a background drone for the tuneless squawks of the urban crows and parakeets that loiter here.  Not requiring of any such thaumaturgic rite of passage, a short afternoon visit suits me just fine. I am left alone with just the crows for company – dark portentous forms that swirl and scatter in the trees above, occasionally coming down to perch scurrilously on the sarcophagi as if they were extras from an Edgar Allen Poe film adaptation. Indeed, this would be the perfect location for a Gothic horror film, especially one that required a steamy colonial setting. Park Street Cemetery is the sort of place where dead souls rising from the ground can seem a distinct possibility – an eerie realm where the hubris of the Raj confronted its own vulnerability and the sad ghosts of empire still linger.

Not requiring of any such thaumaturgic rite of passage, a short afternoon visit suits me just fine. I am left alone with just the crows for company – dark portentous forms that swirl and scatter in the trees above, occasionally coming down to perch scurrilously on the sarcophagi as if they were extras from an Edgar Allen Poe film adaptation. Indeed, this would be the perfect location for a Gothic horror film, especially one that required a steamy colonial setting. Park Street Cemetery is the sort of place where dead souls rising from the ground can seem a distinct possibility – an eerie realm where the hubris of the Raj confronted its own vulnerability and the sad ghosts of empire still linger.