Just three main roads radiate out of Stornoway, the capital of the Isle of Lewis. One heads across mountains towards Tarbet and Harris to the south; another goes east past the island’s airport and along the Eye Peninsula to come to halt at the lighthouse at Tiumpan Head, while a third leads across the island’s moorland interior to reach its west coast. A little way along this last road is the turn-off to Tolsta, a minor road with the most unexpected of endings. The road passes bungalow settlements and sea-facing graveyards as it leads north. In Hebridean terms, this is relatively densely populated terrain — one settlement merging into the next in a loose sprawl known collectively as Back. This stretch of Stornoway’s hinterland might elsewhere be termed green belt were it not a fact that pretty well anywhere on Lewis and Harris could be described as ‘green’.

Just three main roads radiate out of Stornoway, the capital of the Isle of Lewis. One heads across mountains towards Tarbet and Harris to the south; another goes east past the island’s airport and along the Eye Peninsula to come to halt at the lighthouse at Tiumpan Head, while a third leads across the island’s moorland interior to reach its west coast. A little way along this last road is the turn-off to Tolsta, a minor road with the most unexpected of endings. The road passes bungalow settlements and sea-facing graveyards as it leads north. In Hebridean terms, this is relatively densely populated terrain — one settlement merging into the next in a loose sprawl known collectively as Back. This stretch of Stornoway’s hinterland might elsewhere be termed green belt were it not a fact that pretty well anywhere on Lewis and Harris could be described as ‘green’.

Some fifteen miles from Stornoway, a little way beyond the small coastal village of Tolsta, is Garry Beach, a quiet sandy beach with its own car park. A few campervans are parked up here and a rusty caravan is tethered in a boggy field alongside, more likely a base for itinerant workers than a low-rent holiday home. A couple, well wrapped-up against the cool on-shore breeze, are exercising their dog on the beach. A couple of jagged sea stacks rise vertiginously just offshore; half a dozen oystercatchers methodically work the tideline, red beaks wrestling with molluscs. The asphalt road, single track since Tolsta, ends abruptly at the car park and continues only as a rough peat-digging track that winds up the hillside towards a concrete structure. Walk up here and you soon come to it — a bridge over a narrow gorge that, counter-intuitively, appears to be the very end of the road.

The Bridge to Nowhere, as it is generally known, was constructed by Lord Leverhulme, one-time owner of the island, as part of a project to build a road that connected Stornaway with Ness, a fishing village at the northern tip of the island. Like many of Leverhume’s ambitious schemes, good intentions went awry and for a number of reasons the road was never completed. Even today, the only direct way between Tolsta and Ness is on foot, a weary ten-mile slog through soggy moorland that for most people makes the longer, circuitous trip by road via Stornaway and Barvas a more attractive option. The original vision was to build three large farms that would provide dairy produce for fish cannery workers. Alas, the fish canning empire never came to fruition and a lack of both funds and enthusiasm resulted in the road never extended beyond the bridge at Garry Beach.

Head south of Stornoway, over the North Harris Hills to Tarbet and then across the isthmus into South Harris, and you have two options to reach to the ferry port of Leverburgh at the southern tip of this, the largest of the Hebridean islands. The road that skirts the west coast is relatively wide and easy to navigate but the road that runs parallel to the east coast, circumscribing many rocky inlets along the way, is of a very different character. The two coasts of South Harris have strikingly contrasting landscapes. While the west road swoops smoothly past enormous tidal sandy beaches like that at Luskentyre, the narrow east road weaves erratically around rugged inlets and rocky outcrops.

Rough country, largely soil-less, infertile, with very little land suitable for grazing or farming — you might wonder why people might live here in the first case. The reason, of course, as in so many places in the Scottish highland and islands, is because of widespread clearance in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The extensive land clearances of Harris were enforced by the Macleod family who once owned the island and who, to make way for their profitable sheep enterprises, forcibly moved many crofters off the relatively fertile land of the west coast to the far poorer, rocky terrain of the east. As a result, many families migrated to Canada to seek a better, more secure life, while those who remained struggled to survive by digging ‘lazy beds’ for potato-growing — labour-intensive raised beds in which the thin poor soil was bulked out and enriched with seaweed and straw. Never was the word ‘lazy’ so misappropriated.

To travel the Bays Road, as the C79 east coast road is better known, is to witness a dramatic sweep of exposed gneiss, sky and water, with ever-changing glimpses of narrow rocky inlets, dark reed-filled pools and peat-stained streams the colour of strong-brewed tea. The road is not for drivers of a nervous disposition – narrow even for a single lane, with a general allocation of passing spaces, it is a constantly winding tour-de-force where each mile covered seems more like five. Stark, barren, primeval: the landscape is far from bucolic but it is undeniably beautiful. Sheep wander across the road with impunity; white-tailed eagles and buzzards spiral slowly overhead; curious ravens perch on rocks eyeing the sporadic passing traffic like pensioners on a park bench. For the briefest of moments, a pair of golden eagles make an appearance silhouetted high above a ridge. At the road’s highest point, the peaks and headlands of the Isle of Skye show themselves to the east across the wave-flecked Little Minch. The sea is translucent, deepest blue; a CalMac ferry is halfway across the channel steadfastly plying its twice-daily journey to Uig on Skye. In the diamond-clear light, the far-distant Cuillin Hills can be seen glinting crystalline in the sun. Deprived of a decent livelihood by uncaring landlords, you can only reflect that the crofters who were banished to this unwelcoming, unworkable terrain were at least given possession of some of the finest viewpoints in the kingdom.

Kyrgyzstan does not have much of a railway system. A branch line from Moscow extends down from Kazakhstan to Bishkek, the Kyrgyzstan capital; another offers an excruciatingly slow service to Balykchy on Lake Issyk-Kul. Another line extends from Jalal-Abad in the south into Uzbekistan, although trains no longer run on this one. All of these routes date back to Soviet times but even then, Kyrgyzstan, or the the Kyrgyz Soviet Socialist Republic as it was in those days, sat on the outer fringes of the USSR, closer to China than to Moscow. All the more surprising then that, wherever you go in post-independence Kyrgyzstan, you tend to see Soviet-era railway carriages re-located and re-purposed as dwellings, shops, storerooms and even roadside tea-houses. What is most striking is how these are often located far away from a railway line or anything that even resembles a serviceable road. Bump along a rough stony track up to an isolated jailoo (alpine meadow with summer grazing) and the chances are that the nomadic family you meet there will have use of a rusting railway wagon parked somewhere near their yurt. Yurts are ubiquitous in the mountains in summer, and so central to the Kyrgyz way of life that the tunduk, the circular wooden centrepiece of the roof, appears on the national flag. But recycled decommissioned railway wagons have their part to play too, even if rusted metal is less aesthetically pleasing than white felt. In poor countries undergoing rapid transition like Kyrgyzstan, such a resource is too useful to be wasted.

Kyrgyzstan does not have much of a railway system. A branch line from Moscow extends down from Kazakhstan to Bishkek, the Kyrgyzstan capital; another offers an excruciatingly slow service to Balykchy on Lake Issyk-Kul. Another line extends from Jalal-Abad in the south into Uzbekistan, although trains no longer run on this one. All of these routes date back to Soviet times but even then, Kyrgyzstan, or the the Kyrgyz Soviet Socialist Republic as it was in those days, sat on the outer fringes of the USSR, closer to China than to Moscow. All the more surprising then that, wherever you go in post-independence Kyrgyzstan, you tend to see Soviet-era railway carriages re-located and re-purposed as dwellings, shops, storerooms and even roadside tea-houses. What is most striking is how these are often located far away from a railway line or anything that even resembles a serviceable road. Bump along a rough stony track up to an isolated jailoo (alpine meadow with summer grazing) and the chances are that the nomadic family you meet there will have use of a rusting railway wagon parked somewhere near their yurt. Yurts are ubiquitous in the mountains in summer, and so central to the Kyrgyz way of life that the tunduk, the circular wooden centrepiece of the roof, appears on the national flag. But recycled decommissioned railway wagons have their part to play too, even if rusted metal is less aesthetically pleasing than white felt. In poor countries undergoing rapid transition like Kyrgyzstan, such a resource is too useful to be wasted.

Just three main roads radiate out of Stornoway, the capital of the Isle of Lewis. One heads across mountains towards Tarbet and Harris to the south; another goes east past the island’s airport and along the Eye Peninsula to come to halt at the lighthouse at Tiumpan Head, while a third leads across the island’s moorland interior to reach its west coast. A little way along this last road is the turn-off to Tolsta, a minor road with the most unexpected of endings. The road passes bungalow settlements and sea-facing graveyards as it leads north. In Hebridean terms, this is relatively densely populated terrain — one settlement merging into the next in a loose sprawl known collectively as Back. This stretch of Stornoway’s hinterland might elsewhere be termed green belt were it not a fact that pretty well anywhere on Lewis and Harris could be described as ‘green’.

Just three main roads radiate out of Stornoway, the capital of the Isle of Lewis. One heads across mountains towards Tarbet and Harris to the south; another goes east past the island’s airport and along the Eye Peninsula to come to halt at the lighthouse at Tiumpan Head, while a third leads across the island’s moorland interior to reach its west coast. A little way along this last road is the turn-off to Tolsta, a minor road with the most unexpected of endings. The road passes bungalow settlements and sea-facing graveyards as it leads north. In Hebridean terms, this is relatively densely populated terrain — one settlement merging into the next in a loose sprawl known collectively as Back. This stretch of Stornoway’s hinterland might elsewhere be termed green belt were it not a fact that pretty well anywhere on Lewis and Harris could be described as ‘green’.

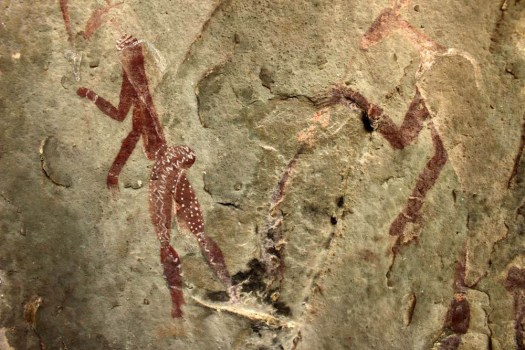

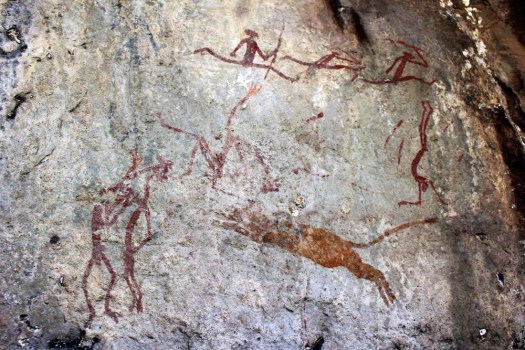

One of the highlights of my recent trip to South Africa was to see some really well-preserved rock art. The cave paintings were made by the San people, the hunter-gatherers who inhabited the Drakensberg mountain region in KwaZulu-Natal province close to the Lesotho border before the incoming Zulus drove them from the land. The rock paintings date from between 2,000 and 200 years ago and the best preserved are those found in south-facing caves where there is never any direct sunlight. One such cave is that found beneath Lower Mushroom Rock in the central Drakensberg.

One of the highlights of my recent trip to South Africa was to see some really well-preserved rock art. The cave paintings were made by the San people, the hunter-gatherers who inhabited the Drakensberg mountain region in KwaZulu-Natal province close to the Lesotho border before the incoming Zulus drove them from the land. The rock paintings date from between 2,000 and 200 years ago and the best preserved are those found in south-facing caves where there is never any direct sunlight. One such cave is that found beneath Lower Mushroom Rock in the central Drakensberg. The figures show hunting scenes involving various animals indigenous to the region, like eland, which are still numerous, and lions, which are no longer found here. Other paintings depict animal skin-wearing shamans in trances, a state of mind artificially (and partially chemically) induced to connect them with the spirit world in order to foresee the future and cure illnesses.

The figures show hunting scenes involving various animals indigenous to the region, like eland, which are still numerous, and lions, which are no longer found here. Other paintings depict animal skin-wearing shamans in trances, a state of mind artificially (and partially chemically) induced to connect them with the spirit world in order to foresee the future and cure illnesses. The paintings were made using brushes made from animal hair and dyes and pigments extracted from indigenous plants and mineral-rich rocks. The colour and attention to detail of the paintings are remarkable, and even depict the typically steatopygic buttocks characteristic of the San bushmen who nowadays mostly occupy the arid regions of Botswana and Namibia.

The paintings were made using brushes made from animal hair and dyes and pigments extracted from indigenous plants and mineral-rich rocks. The colour and attention to detail of the paintings are remarkable, and even depict the typically steatopygic buttocks characteristic of the San bushmen who nowadays mostly occupy the arid regions of Botswana and Namibia.

![north-south_divide_UK_no_labels_blue_red_small[1]](https://eastofelveden.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/north-south_divide_uk_no_labels_blue_red_small1.jpg?w=525)