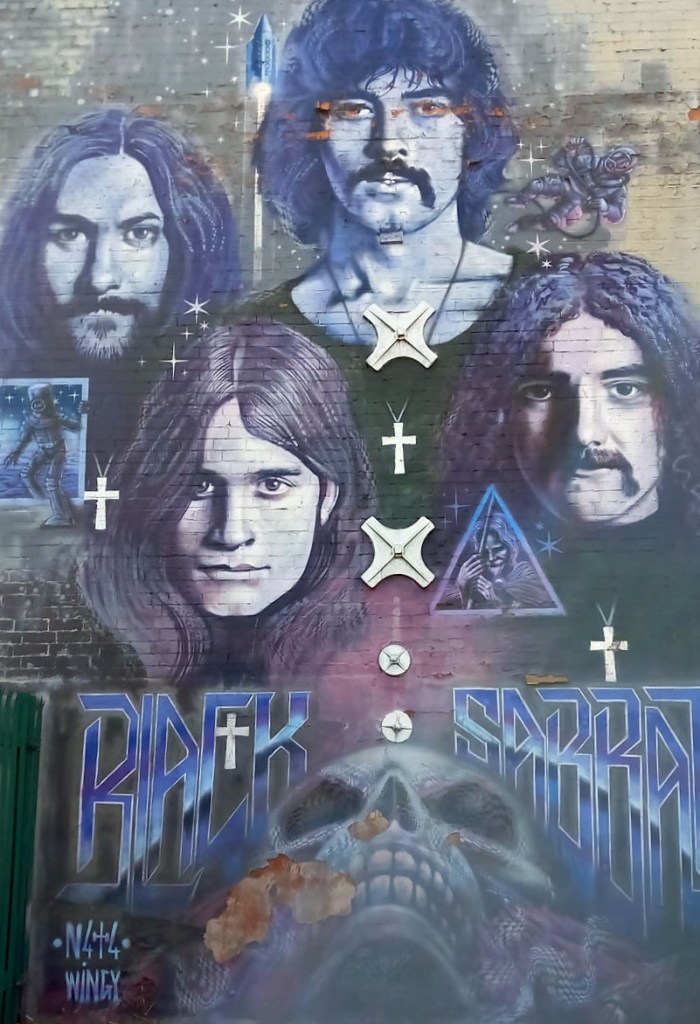

We were driving home from North Wales, and it is a long way to East Anglia from there. So we were looking for a break in the journey somewhere: a place to rest overnight before A14-ing onwards to Norwich? While it might not be everybody’s destination of choice, Dudley, de facto capital of England’s Black Country, has some points in its favour, its West Midlands location midway between coasts being one of them. Besides, I wanted to have a look at Wren’s Nest, the geopark on the town outskirts, where all manner of weird and wonderful fossils from the Silurian period might be found.

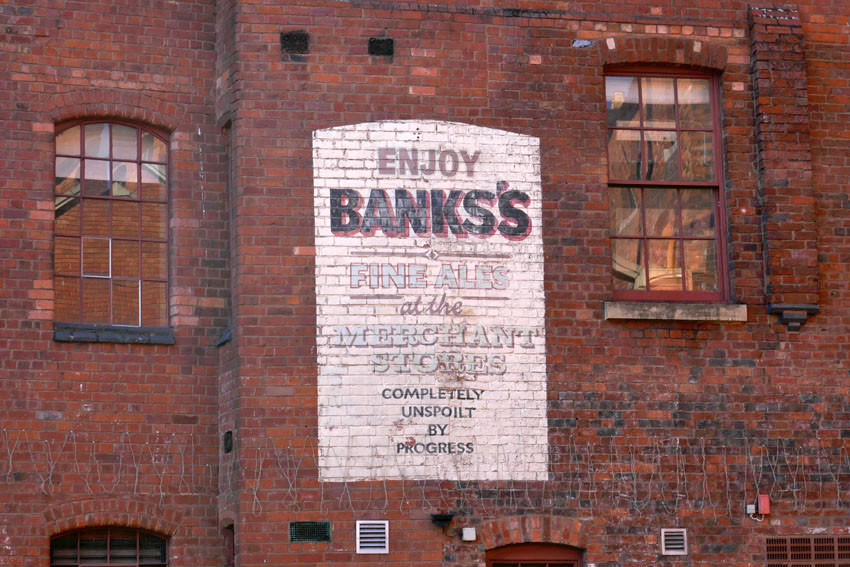

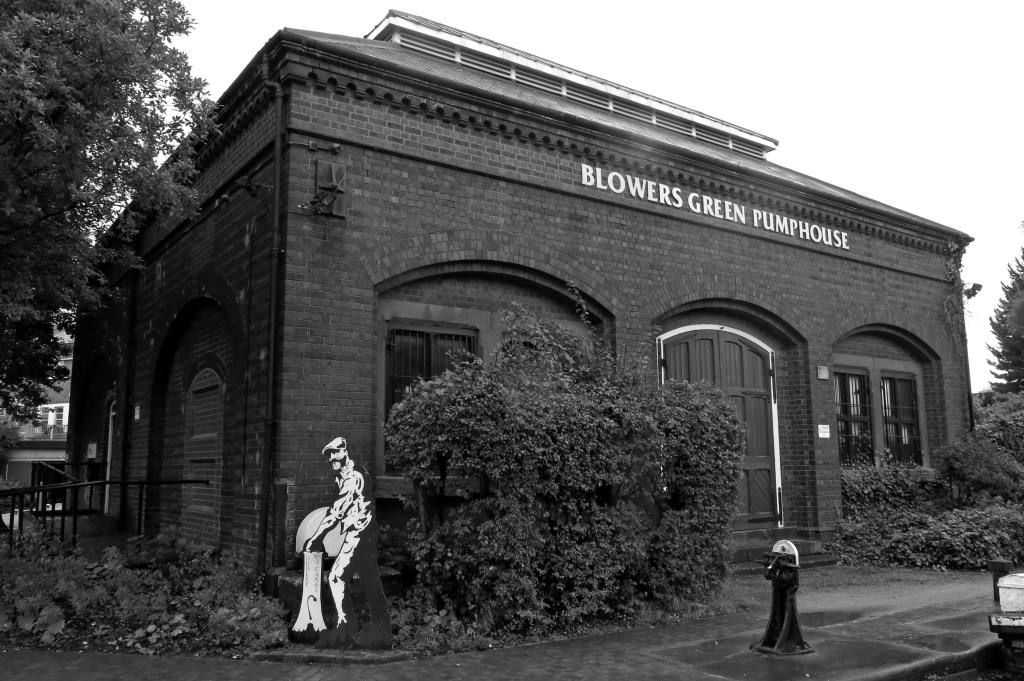

I had been here before, several years earlier, a brief stop on a coast to coast pilgrimage that I wrote about in my book Westering. Back then I had passed through Dudley as I traced my way through the Birmingham – Black Country conurbation by way of its extensive canal network; an interesting route, although Venice didn’t spring very much to mind as I traipsed westwards through a decayed, post-industrial landscape.

I wrote then:

I arrived at a large, five-way roundabout and a dual-carriageway, which I followed further uphill towards Dudley Castle, which I could see, noble but not entirely fairytale, flying its flag on top of the hill ahead. The next roundabout held several large, Black Country-themed sculptures: a steel crucible, bronze cannon, heraldic lion and medieval plough. It looked as if Dudley was doing its best to make the most of its industrial heritage. I wanted to take a closer look but was stuck on the wrong side of the dual carriageway with no safe means of crossing. Eventually, I spotted a footbridge ahead that conveniently led me straight to Dudley’s bus station at the foot of Castle Hill, an outcrop of the Wenlock Group limestone that had played a significant part in the town’s industrial development.

This time, coming from Wales by way of Shrewsbury and Telford, we came upon this same roundabout as we were driving around looking for the hotel we had booked for the night. Travelodge found, and bags deposited, we went off in search of food and drink. A peremptory Google search of the vicinity revealed a pub close to the castle that might be a possibility but when we arrived at the Fellows things didn’t look very promising. A tribute singer was belting out a cover of Red Red Wine by UB40 at deafening volume and the courtyard was packed with smokers who were intent on avoiding the aural onslaught inside. Besides, it was Sunday evening and the availability of lunchtime roasts had been and gone. It looked as if we would have to try elsewhere.

On the way up to the Fellows we had passed an even more unpromising establishment on Castle Hill, a single-roomed place that called itself the Star Bar, which resembled more a garage lock-up than a place for food and drink, although the former was clearly available as boisterous yam yam* voices echoed from behind it half-closed metal portal. Also on Castle Hill was a once-splendid Art Deco cinema that now served as a Jehovah’s Witness Kingdom Hall. Next door, a Tudor Gothic pile had similarly been converted to serve as a place of worship for the town’s Muslim community: Dudley Central Mosque. The building, I found out later, was Grade II-listed and had once been a school.

* yam yam = Black Country dialect

Across the road from the Fellows, a grand statue of the First Earl of Dudley stood at the top of the town’s pedestrianised shopping zone and market place. A little further on we passed St Edmund’s Church, an 18th-century replacement of earlier place of worship of Anglo-Saxon origin destroyed in the Civil War. To symbolise its dedication, twin crowns and the arrows of the saint’s martyrdom were on display in front of the church entrance.

This being Sunday evening, the area was largely deserted; its market stalls locked up, although some of the shop fronts gave the impression of having been closed up for some time. There were several interesting statues scattered about to restore some sense of civic pride. Most notable of these was that of local football hero Duncan Edwards. Born in Dudley in 1936, Edwards had been a Manchester United ‘Busby Babe’ and highly respected England defender before dying tragically, aged just 21, from injuries sustained in the 1958 Munich Air Disaster. Further down, just beyond the market place, was a life-size bronze statue of a top-hatted Victorian gentleman sitting on a bench: the poet Ben Boucher (1769 – 1851), who wrote ‘Lines on Dudley Market’, some of which were etched into the curved Portland stone bench. While Boucher lived a much longer life than the unfortunate footballer, the Dudley Poet’s own sad fate was to end up impoverished in the town workhouse.

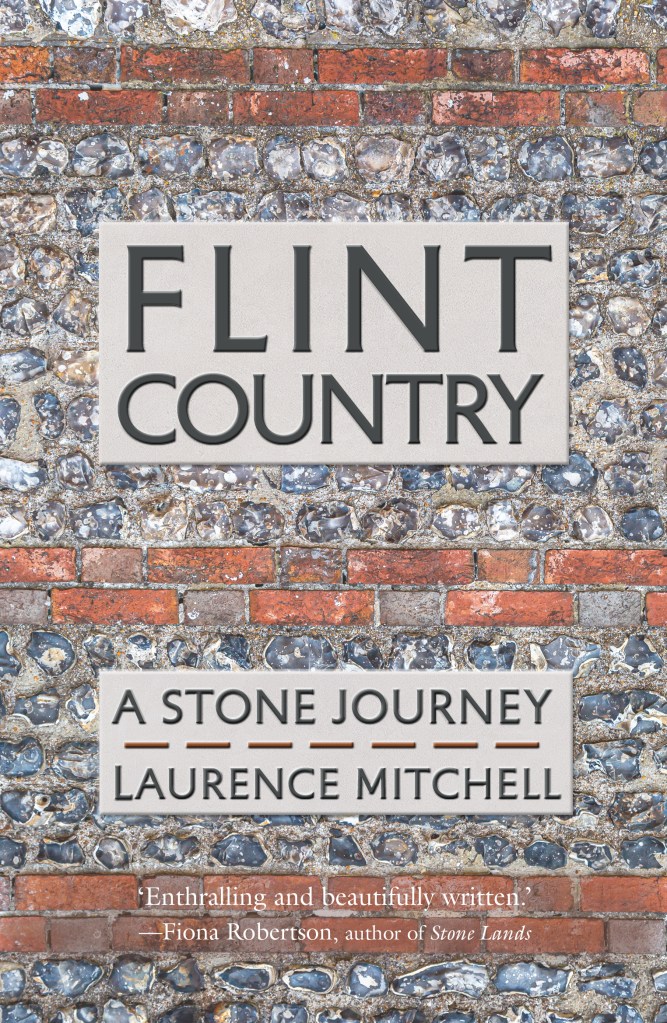

This brief glimpse of the town centre reinforced the impression I had taken from my previous visit: one of decline and closure, one of faded glory. The re-purposing of grand old buildings; the closure of town centre shops and department stores – out-competed ever since the opening of Merry Hill Shopping Centre at nearby Brierley Hill towards the end of the last century. Counter to this sense of decline were the upbeat Town Trail pavement plaques that told with pride the town’s unique geological and industrial history. It was here in the Black Country that the Industrial Revolution had originated and then swiftly gained momentum in the late 18th century. A serendipitous convergence of factors had come into play. The area had all the necessary raw materials – coal, limestone and iron ore. It had – or, rather, soon acquired – the labour, skills and engineering talent. It also had the means of distribution – canals, and later railways. It could even be argued that the Anthropocene – the recent epoch in which human activity has been the dominant factor in changing the world around us – began hereabouts. I touch upon this in the final chapter of my recent book Flint Country, where I write:

The precise date of its onset remains a matter of debate. James Lovecock, originator of the Gaia concept, claims that the Anthropocene started with the Industrial Revolution in the early nineteenth century, the period in modern history when the use of fossil fuels for manufacturing and transport got fully underway. Fine-tuning this connection between the dominance of human influence and technological progress, it could even be said that the Anthropocene began with the invention of Thomas Newcomen’s steam-powered pump, a machine first used to remove water from a coal mine near Dudley in the English Black Country in 1712.

Next morning we made our way to Wren’s Nest, where I noticed that the suburban streets approaching the site had pleasingly apposite names like Silurian Mews and Fossil View. It was a grey, overcast, not-very-warm-for-August sort of day, and the site was fairly quiet apart from a couple of dog-walkers and kids on bikes. At the entrance, an information board gave us the lowdown on the site’s remarkable geological pedigree. Wren’s Nest is effectively a 428 million-year-old tropical seabed that was once covered by coral reefs and uplifted within the Much Wenlock limestone that gifted this region its industrial resources.

The prize fossil here is a species of trilobite, Calymene bumenbachii, known colloquially as the ‘Dudley Bug’, which looks like a scarily, super-sized woodlice, although it is more closely related to modern day crabs. To find one of these would have made me very happy but they proved to be elusive. What I did find after an hour and a half of turning over scree were several bits of coral and all manner of fossilised brachiopod shells. Best of all was a small flat piece of rock embedded with dozens of tiny shells: a fragment of ancient sea floor that revealed a microcosm of life 428 million years ago, a time when the existing continents were yet to separate and the territory of what would become the British Isles lay south of the Equator. To contemplate such scales of time and distance takes the breath away. William Blake wrote of seeing ‘the world in a grain of sand’. Here you could see a long-vanished world in a small piece of rock.

We left the car park and drove northeast through Tipton and Wednesbury to reach the M6 with its relentless parade of thundering traffic. It was a timely reminder that we were now firmly back in the age of man and machine, the Anthropocene. In comparison with the aeons that had passed since the fossils of Wren’s Nest were deposited at the bottom of a tropical ocean, the 19th-century heyday of the Industrial Revolution in the Black Country with its smoke, red-sky furnaces and metal-clanging workshops was as if just yesterday.