With only the forthcoming Jubilympics stealing more media thunder so far this year, it has been nigh on impossible to ignore the fact that April 2012 marks the centenary of the sinking of a certain trans-Atlantic passenger liner. One hundred years ago this month, RMS Titanic, a vessel considered virtually unsinkable, disappeared beneath the North Atlantic’s icy waters on its maiden voyage, along with most of its crew and lower class passengers. The cause of this tragic event was seemingly the combined effect of hubris and a sneaky, yet massive, iceberg.

With only the forthcoming Jubilympics stealing more media thunder so far this year, it has been nigh on impossible to ignore the fact that April 2012 marks the centenary of the sinking of a certain trans-Atlantic passenger liner. One hundred years ago this month, RMS Titanic, a vessel considered virtually unsinkable, disappeared beneath the North Atlantic’s icy waters on its maiden voyage, along with most of its crew and lower class passengers. The cause of this tragic event was seemingly the combined effect of hubris and a sneaky, yet massive, iceberg.

What does this have to do with a little-known corner of the Caucasus? Well, it is partly connected with the sense of irony so readily displayed in the post-Soviet territories of the Caucasus region. I remember spotting a restaurant on my first visit to Baku that was called, of all things, ‘Lady Diana’ (smallish helpings presumably) but even this pales into insignificance when compared to a hotel I once stayed at in the unrecognised territory of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Nagorno-Karabakh, formerly part of Azerbaijan, now a de facto independent state (but only recognised by three fellow non-UN states – Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Transnistria), is a very odd place – and a sad place too, with visible traces of war damage almost everywhere. Given the state’s poverty, isolation and lack of infrastructure it might seem surprising to come across a hotel of any description in a small village, let alone one called ‘The Titanic’, but the small lumber village of Vank in northern Nagorno-Karabakh not only has a guest house that answers that description but also one that is actually built in the form of a ship.

The Titanic Hotel – officially Hotel Eclectica but everyone seems to calls it ‘Titanik’ and that is what it said on my restaurant receipt – is a striking edifice built in the form of a ship. This brick-built simulacrum even goes as far as having port-holes for some of its windows. In front of it stands a small swimming pool (no icebergs!) that must, almost certainly, be the only one in all of northern Nagorno-Karabakh. The hotel must be a thoroughly disturbing phenomenon to come across out here in the boondocks if you were not expecting to find it; it’s an arresting enough sight even when anticipated.

The Hotel Eclectica/Titanic is one of the most surreal sites you are ever likely to see but the village is the oddest of places too. Vank is the birthplace of a Moscow millionaire lumber baron called Levon Hayrapetyan who as well as asphalting the 12km-long road to the village has ploughed plenty of money back into his home village, building a school, a lumber mill and this highly incongruous hotel. Part of Hayrapetyan’s vision for the village of his birth is to develop tourism in the area, hence the hotel. It seems a long shot considering its isolation and the fact that Nagorno-Karabakh is the remnant of a frozen conflict and officially does not even exist. Technically speaking, Nagorno-Karabakh still belongs to Azerbaijan, although virtually all ethnic Azeris have left since the bloody conflict of the 1990s.

I spent a few days in Nagorno-Karabakh back in 2008, having first obtained a visa in Yerevan, the Armenian capital. The colourful ‘visa’, which I took the precaution of not sticking into my passport, was hardly glanced at when I arrived at the border post in the crowded marshrutka that plies daily between Yerevan and the Nagorno-Karabakh capital Stepanakert. After a couple of days in Stepanakert – a bit of a threadbare Soviet theme park without really trying to be – I took another marshrutka to Vank for an overnight stay.

I spent a few days in Nagorno-Karabakh back in 2008, having first obtained a visa in Yerevan, the Armenian capital. The colourful ‘visa’, which I took the precaution of not sticking into my passport, was hardly glanced at when I arrived at the border post in the crowded marshrutka that plies daily between Yerevan and the Nagorno-Karabakh capital Stepanakert. After a couple of days in Stepanakert – a bit of a threadbare Soviet theme park without really trying to be – I took another marshrutka to Vank for an overnight stay.

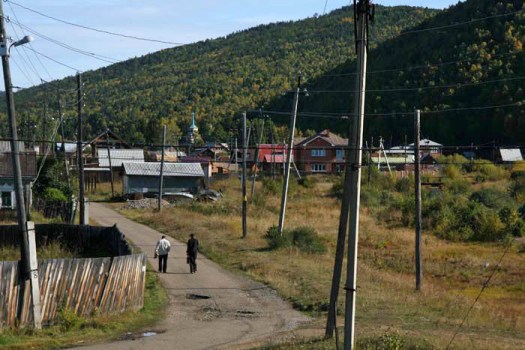

The village lies deep in a wooded valley with wispy strands of low clouds kissing the nearby hills, atop one of which stands the mysterious Gandzasar Monastery. I managed to get a room at the Titanic, although they didn’t really seem very keen on having a lone foreigner like me stay, perhaps disbelieving that I might seriously want to spend the night there. After paying 7,000 Armenian drams ($20) and leaving my bag I walked up the neatly tarmaced road to the monastery on the hill, which was swathed in mist so thick that it was impossible to see the church until the very last minute of ascent. In the monastery grounds I encountered a friendly trio of chain-smoking Armenian men but, after we had posed for group photographs together and they had sped off down the hill in their Lada, I was completely alone once more – the resident monks were either absent or keeping a very low profile. Not quite alone though. Mooching around, I noticed a small curved-beaked bird poking around on the stone of the gable. A sparrow? No, a wallcreeper – an exotic-looking mountain bird more at home on isolated cliff faces than the stone walls of churches. Perhaps, like me, it had become disoriented by the swirling mist that flanked the monastery like the overenthusiastic use of dry ice in a Hammer Horror production?

Later, walking up out of the village through lovely wooded countryside along a section of the long-distance Janapar Trail I came across a few more locals: friendly Armenian women at a village kiosk who wanted me to take their photograph and another villager who beckoned me into his garden to drink vodka with him. Less welcoming though, was the policeman who gruffly insisted on seeing my dokumenti. As he was dressed in civilian clothes I countered by asking to see his identification, which pissed him off a bit but made his friend roar out loud with laughter. I stood my ground and soon the policeman just walked off in a huff trailed by his still giggling accomplice.

Later, walking up out of the village through lovely wooded countryside along a section of the long-distance Janapar Trail I came across a few more locals: friendly Armenian women at a village kiosk who wanted me to take their photograph and another villager who beckoned me into his garden to drink vodka with him. Less welcoming though, was the policeman who gruffly insisted on seeing my dokumenti. As he was dressed in civilian clothes I countered by asking to see his identification, which pissed him off a bit but made his friend roar out loud with laughter. I stood my ground and soon the policeman just walked off in a huff trailed by his still giggling accomplice.

By the time I got back to the hotel late afternoon the place had been virtually taken over by a wedding party and so things had become pretty chaotic. Nevertheless, I was hungry. The hotel’s ‘Van Gogh’ restaurant had a Chinese couple working there (who knows how they found their way here to Vank?), which might have been a good sign, although it seemed they were only capable of providing food for themselves and pre-ordered wedding feasts. Eventually, after much negotiation and shaking of heads, I managed to order an overpriced plate of barbecued mutton, which arrived after a full hour’s wait accompanied by a huge dish of fresh coriander.

One night was enough. I caught the early morning marshrutka back to Stepanakert the next day. Among the suspicious faces that turned my way when I took my seat was the policeman from the previous day. This time he was in uniform – quite high-ranking it would seem judging by the pips on his lapel. He didn’t bother asking for my passport this time.

One night was enough. I caught the early morning marshrutka back to Stepanakert the next day. Among the suspicious faces that turned my way when I took my seat was the policeman from the previous day. This time he was in uniform – quite high-ranking it would seem judging by the pips on his lapel. He didn’t bother asking for my passport this time.

Postscript: I am aware that Vank is not the only place in the world with a Titanic Hotel. There’s also a luxury beach hotel resort called Titanic in Antalya in Turkey, another beach resort in Hurghada, Egypt, a business hotel in Istanbul and others in Albania, Vietnam and Poland. You would be hard pushed to find this particular one on TripAdvisor though. The Hotel Titanic, Vank, Nagorno-Karabakh is not only a very odd place to stay, it is the Caucasus region’s very own Fawlty Towers.

For those interested in finding out more about the long-distance Janapar Trail you can look at my feature for Walk magazine here – the title Global Walk: Azerbaijan was not my idea.

The ruined castle at Baconsthorpe in north Norfolk can hardly be described as ‘hidden’ but it does lie nicely tucked away from the limelight, located at the end of a dusty farm track at some distance from the main road. Strictly speaking, it is not really a castle, more a fortified manor house, but with a large moat, thick flint walls and a no-nonsense gatehouse, unlawful entry by unwelcome visitors would certainly not have been easy.

The ruined castle at Baconsthorpe in north Norfolk can hardly be described as ‘hidden’ but it does lie nicely tucked away from the limelight, located at the end of a dusty farm track at some distance from the main road. Strictly speaking, it is not really a castle, more a fortified manor house, but with a large moat, thick flint walls and a no-nonsense gatehouse, unlawful entry by unwelcome visitors would certainly not have been easy. To reach Baconsthorpe Castle you can drive right up to the door from the village of the same name. The site is managed by English Heritage and there is no charge for car park or entry. Better still, you could walk from Bodham, the village to the north that straddles the busy Holt to Cromer road. Certainly, to follow the footpath up and down the shallow valley before skirting Baconsthorpe Wood, makes arrival here a little more special. With luck, as the castle comes into view after leaving the wood you will be greeted by some of the sleek chestnut horses that graze in the meadow beside it.

To reach Baconsthorpe Castle you can drive right up to the door from the village of the same name. The site is managed by English Heritage and there is no charge for car park or entry. Better still, you could walk from Bodham, the village to the north that straddles the busy Holt to Cromer road. Certainly, to follow the footpath up and down the shallow valley before skirting Baconsthorpe Wood, makes arrival here a little more special. With luck, as the castle comes into view after leaving the wood you will be greeted by some of the sleek chestnut horses that graze in the meadow beside it.

Next door to the gatehouse stands a group of old farm buildings that have seen better days — no doubt a bustling, energetic place before the middle of the last century, now their only role appears to be that of the storage of farm machinery. Within the gate there’s a compound and a bridge across to the inner court. Here, to the east, the moat widens to become a large pond – known as a ‘mere’ in these parts – which provides luxury accommodation for the ducks that thrive on the sandwich crumbs left by picnicking visitors. Swallows swoop low and fast over the water to grab unsuspecting flies but there’s little sound other than a summery rustle of leaves, the narcotic coo of pigeons and, during school holidays, the gleeful cries of children here with their parents.

Next door to the gatehouse stands a group of old farm buildings that have seen better days — no doubt a bustling, energetic place before the middle of the last century, now their only role appears to be that of the storage of farm machinery. Within the gate there’s a compound and a bridge across to the inner court. Here, to the east, the moat widens to become a large pond – known as a ‘mere’ in these parts – which provides luxury accommodation for the ducks that thrive on the sandwich crumbs left by picnicking visitors. Swallows swoop low and fast over the water to grab unsuspecting flies but there’s little sound other than a summery rustle of leaves, the narcotic coo of pigeons and, during school holidays, the gleeful cries of children here with their parents. What is of particular interest here is not so much what remains of the castle but what has happened to those parts that are absent. Certainly, it is not just the effect of the elements. Built as a 15th-century manor house by the locally powerful Heydon family, the inner gatehouse and fortified house were added at the time of the Wars of the Roses. Some of the buildings were converted into a textile factory at the height of Norfolk’s profitable wool trade in the Tudor years. The outer gateway came in the Elizabethan period.

What is of particular interest here is not so much what remains of the castle but what has happened to those parts that are absent. Certainly, it is not just the effect of the elements. Built as a 15th-century manor house by the locally powerful Heydon family, the inner gatehouse and fortified house were added at the time of the Wars of the Roses. Some of the buildings were converted into a textile factory at the height of Norfolk’s profitable wool trade in the Tudor years. The outer gateway came in the Elizabethan period. The voices of wealthy landowners, shepherds, textile workers and Roundhead soldiers would all once have echoed here within the castle’s sturdy walls. Now, apart from the subdued utterances of occasional visitors, they stand silent: mute witnesses to history; flint and brick repositories of the past.

The voices of wealthy landowners, shepherds, textile workers and Roundhead soldiers would all once have echoed here within the castle’s sturdy walls. Now, apart from the subdued utterances of occasional visitors, they stand silent: mute witnesses to history; flint and brick repositories of the past.