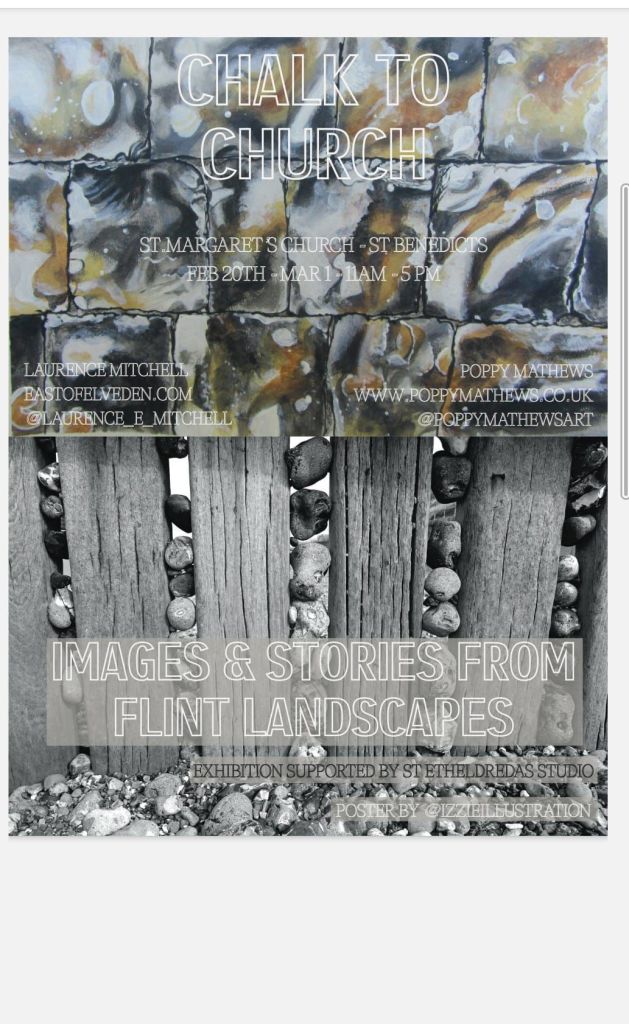

I am currently involved in an art exhibition at St Margaret’s Gallery, St Benedicts St, Norwich. The exhibition is mixed media, with paintings by Poppy Mathews (@poppymathewsart) and photographs and text by me. It is all very flint-themed and, for my part at least, relates closely to my recent book. Some of the text is taken from the book, Flint Country; some was written specifically for the exhibition.

Here is a small sample of what you can see at the exhibition. Of course, if you just happen to find yourself in the Norwich area over the next week then please drop in to have a look. Chalk to Church is open 11.00-17.00 daily and will run until Sunday, March 1st.

Flint 1 – Poppy Mathews

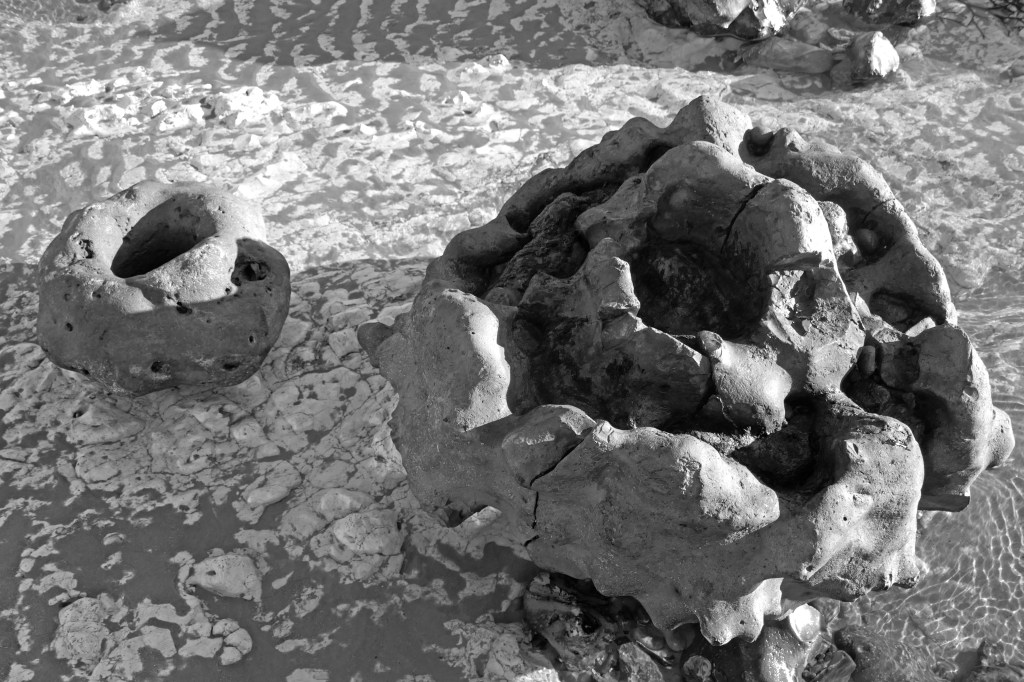

Paramoudras, West Runton Beach, Norfolk

Flint sometimes naturally takes the shape of a nest-like structure in the form of a paramoudra. It is the sort of nest that you might imagine a small dragon laying a clutch of eggs in.

Many of the larger flints that lay scattered were paramoudra – tubular in shape and either hollow in the middle or filled with chalk like a sculptured vol-au-vent.

The name paramoudra is Irish, deriving from the Gaelic peura muireach, meaning ‘sea pears’. They have also been called ‘ugly Paddies’ in the past, which seems a little harsh, even racist. They are beautiful in their own way. Their Norfolk name of ‘potstones’ makes more sense, as some of the better formed ones could easily be adapted to serve as plant containers. Paramoudra, like all flints, are actually pseudofossils. They are generally thought to be fossilised barrel sponges but the precise process of their formation is not fully understood.

Flint Country

Orford Ness, Suffolk

A warning, its message lost to the shingle

Stray Cold War ordnance? Or tide?

This secret place, its geography both cause and effect

A zone of intrigue, longshore drift and flint music

Liminal, littoral, literal

A spit that resembles an island yet is called a ‘ness’ – an Anglo-Saxon word for ‘nose’ that describes a headland or promontory – Orford Ness is a luminous landscape of shingle, birds and secrecy. A one-time top secret weapons testing site, it continues to exude an air of secrecy sufficient to make even the modern-day visitor feel as if that they are standing on forbidden territory. Its former exclusion from the public gaze is now part of its appeal but, even without this, Orford Ness is a highly evocative sort of place. In recent years, the spit’s unique combination of dark history and melancholy landscape has resulted in it becoming a holy ground for a particularly niche variety of art and literature. All have tried to tap into the Ness’s peculiar genius loci.

Flint Country

Guildhall – Poppy Mathews

Flint wall, Museum of Norwich at the Bridewell

A night-black wall, early medieval

Its joints, Inca-snug, four-square

Yet not quite square

A thousand faces to the world, a mosaic of time-lost oceans

Visitors to Norwich have long noted the abundance and splendour of its flint buildings. The equestrian traveller Celia Fiennes visiting the city in 1698 observed that Norwich, in addition to having ‘a great number of dissenters’ was ‘a rich, thriving industrious place’:

… by one of the churches there is a wall made of flints that is headed very finely and cut so exactly square and even to shut in one to another that the whole wall is made without cement at all they say… it looks well, very smooth shining and black.

The building whose wall Celia Fiennes was so impressed with still stands and for almost a century has served as the city’s Bridewell Museum. As the plaque by the museum entrance confirms, it has long been considered ‘the finest piece of flintwork in England’.

Flint Country

Ruin of St Mary’s Church, Saxlingham Thorpe, Norfolk

Given sufficient time, ruins can blend into the landscape and accumulate folklore along with the ivy and bramble. A ruin invariably provokes a sense of melancholy – a psychological linkage of place and emotion that has been recognised since antiquity. There is even an Old English word for it: dustsceawung, which translates as ‘the contemplation of dust’, although ‘dust’ here should be considered in the broader sense of that which remains after destruction, along with the concomitant awareness that all things go this way eventually.

Norfolk has more than its fair share of ruins. In particular, it abounds with a wealth of long-abandoned flint-built churches. Mostly these ended up as ruins because of abandonment and their subsequent deterioration over the centuries that followed. Others were deliberately dismantled, partially at least for the building stone they held, which would then be recycled for use in new churches, houses and farm buildings.

Flint Country

Flint 5 – Poppy Mathews