There’s a walk through Norwich’s western edgeland that Jackie and I must have done a hundred times. It begins close to a supermarket at Eaton, Norwich’s wealthy southern suburb, and follows the bank of the meandering River Yare upstream towards the broad at the University of East Anglia before the river veers west towards its central Norfolk source. A peaceful walk, frequented by just the odd suburban dog-walker and jogger, it is the epitome of the countryside in the city or, rather, its leafy urban fringe. Drooping willows frame the water, small fish swim, birds tweet in the bushes and reedbeds; herons and kingfishers are regularly sighted along the river. The houses on the opposite bank, with their expansive back gardens and private river frontage, give rise to occasional bouts of envy but on the whole we are simply happy to have the opportunity to walk somewhere like this so close to home.

There’s a walk through Norwich’s western edgeland that Jackie and I must have done a hundred times. It begins close to a supermarket at Eaton, Norwich’s wealthy southern suburb, and follows the bank of the meandering River Yare upstream towards the broad at the University of East Anglia before the river veers west towards its central Norfolk source. A peaceful walk, frequented by just the odd suburban dog-walker and jogger, it is the epitome of the countryside in the city or, rather, its leafy urban fringe. Drooping willows frame the water, small fish swim, birds tweet in the bushes and reedbeds; herons and kingfishers are regularly sighted along the river. The houses on the opposite bank, with their expansive back gardens and private river frontage, give rise to occasional bouts of envy but on the whole we are simply happy to have the opportunity to walk somewhere like this so close to home.

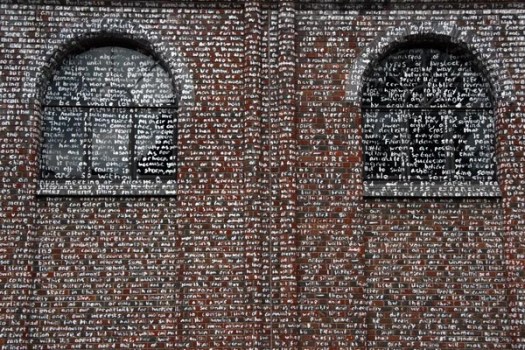

From the car park where the walk begins, a path leads to the river next to the medieval bridge that once marked the principal route into Norwich from the south. There is an attractive white wooden mill house here, a gushing weir and a NO FISHING sign. The path follows the river under a flyover that carries the bulk of traffic into the city these days – at weekends, a constant buzz of cars speeding into Norwich for retail therapy. Compared to the fine curves and warm sandstone of the nearby bridge, this has all the charm of a multi-storey car park: quotidian concrete and murky, permanently shaded water sheltering that ubiquitous creature of the urban waterway – a supermarket shopping trolley. A Ballardian microcosm, this edgeland non-place provokes an interruption in the pastoral flow of the walk; a frontier to be crossed (or underpassed) before continuing along the riverbank beyond. The smooth round pillars that hold up the flyover are splattered with spray-can ciphers – warnings and portents perhaps? A couple spell out ANARCHY, or words to that effect. Another graffito, more considered, pronounces HAPPINESS DOES NOT HAVE A BAR-CODE.

From the car park where the walk begins, a path leads to the river next to the medieval bridge that once marked the principal route into Norwich from the south. There is an attractive white wooden mill house here, a gushing weir and a NO FISHING sign. The path follows the river under a flyover that carries the bulk of traffic into the city these days – at weekends, a constant buzz of cars speeding into Norwich for retail therapy. Compared to the fine curves and warm sandstone of the nearby bridge, this has all the charm of a multi-storey car park: quotidian concrete and murky, permanently shaded water sheltering that ubiquitous creature of the urban waterway – a supermarket shopping trolley. A Ballardian microcosm, this edgeland non-place provokes an interruption in the pastoral flow of the walk; a frontier to be crossed (or underpassed) before continuing along the riverbank beyond. The smooth round pillars that hold up the flyover are splattered with spray-can ciphers – warnings and portents perhaps? A couple spell out ANARCHY, or words to that effect. Another graffito, more considered, pronounces HAPPINESS DOES NOT HAVE A BAR-CODE.

On Monday, our walk took an unexpected and delightful turn when we spotted a solitary otter at the mill pond near the bridge. Oblivious to the sign prohibiting fishing, the animal was busy hunting – diving and then resurfacing with just its head showing above the water like a small sleek Labrador. We knew that otters were frequently seen in the area by early-worm fishermen but we had never seen one here ourselves. This time, we were privileged. We watched in silence as the animal worked its way along the water’s edge, shaking the reeds at their base and leaving tell-tale trails of bubbles as it swam underwater. It eventually disappeared somewhere near the weir, just before the flyover, and we remarked on how lucky we had been to have had such a good view.

Five minutes later, I was just about to say something sagacious like, ‘It could be a year before we see one again’, when another otter – probably the same, earlier one displaced further upstream – surfaced beneath a drooping willow. The animal progressed through the reeds at the river’s edge for some time before swimming to the opposite bank, foraging there awhile before returning midstream to dive once more with an effortless flex of its back. We followed it upstream for a full half hour, the otter hyperactive for most of the time – diving for fish, snuffling through vegetation, occasionally sneaking a look back at the two humans and one small dog that were politely in pursuit. We drew so close that we could hear teeth crunching bone as the animal munched the fish it had caught, the otter’s noisy chewing just one aural ingredient in a soundscape that included other familiar echos of the urban fringe in May: small birds chirruping, an overenthusiastic cuckoo (the first heard of the year), chiffchaffs chiff-chaffing, a background thrum of cars on the flyover and the distant eye-ore of the Cambridge train’s air-horn.

We lost track of the otter somewhere in the wider stretch of the river that leads to UEA Broad. It did not matter: our unexpected encounter had been far in excess of anything than we might have hoped for. It didn’t even matter that I did not have my camera with me: if anything, it was liberating to simply observe without the nagging distraction of having to keep a digital record.

We lost track of the otter somewhere in the wider stretch of the river that leads to UEA Broad. It did not matter: our unexpected encounter had been far in excess of anything than we might have hoped for. It didn’t even matter that I did not have my camera with me: if anything, it was liberating to simply observe without the nagging distraction of having to keep a digital record.

Walking back to the car park, I made a short diversion back to the bridge on the off chance that the animal had returned there. No sign. Turning to leave, a metallic blue bullet flashed close to the water and darted beneath the arch of the medieval bridge: a kingfisher, often spotted here but hitherto unseen on this red letter day for wildlife. Happiness does not have a bar-code. True enough.

Beyond the printing works, a

Beyond the printing works, a

![2_THUMB_Credit_Steven_Perilloux[1]](https://eastofelveden.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/2_thumb_credit_steven_perilloux11.jpg?w=300&h=128)

![ts[5]](https://eastofelveden.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/ts5.jpg?w=525)