Today is St Patrick’s Day and March 17 is the supposed date of the 5th-century missionary’s death. Patrick was the forerunner of many early missionaries who came to Irish shores to preach Christianity, the island more receptive to new ideas about religion than its larger neighbour to the east across the Irish Sea. Consequently Ireland abounds with relics and ruins of early Christianity, sometimes in the most improbable of places.

Today is St Patrick’s Day and March 17 is the supposed date of the 5th-century missionary’s death. Patrick was the forerunner of many early missionaries who came to Irish shores to preach Christianity, the island more receptive to new ideas about religion than its larger neighbour to the east across the Irish Sea. Consequently Ireland abounds with relics and ruins of early Christianity, sometimes in the most improbable of places. Sailing around Ireland’s southwest coast, skirting the peninsulas that splay out from the Kerry coast, the two islands of the Skelligs come into view after rounding Bolus Head at the end of the Inveragh Peninsula. Both islands are sheer, with sharp-finned summits that resemble inverted boat keels. The smaller of the two appears largely white at first but increasing proximity reveals that the albino effect is down to a combination of nesting gannets and guano. The acrid tang of ammonia on the breeze and distant cacophony announce the presence of the birds well before the identity of any individual can be confirmed by binoculars.

Sailing around Ireland’s southwest coast, skirting the peninsulas that splay out from the Kerry coast, the two islands of the Skelligs come into view after rounding Bolus Head at the end of the Inveragh Peninsula. Both islands are sheer, with sharp-finned summits that resemble inverted boat keels. The smaller of the two appears largely white at first but increasing proximity reveals that the albino effect is down to a combination of nesting gannets and guano. The acrid tang of ammonia on the breeze and distant cacophony announce the presence of the birds well before the identity of any individual can be confirmed by binoculars. As the boat draws closer, the sheer volume of birds – gannets, fulmars, puffins, terns – becomes plain to see. With something like 70,000 birds, Little Skellig is the second largest gannet colony in the world. But on the larger island of Skellig Michael, although seabirds abound here too, there is also the suggestion of a human presence, albeit an historic one. High up in the rocks, small stone structures can be discerned: rounded domes that are clearly man-made and which soften the jagged silhouette of the island’s summit. These are beehive cells, the dry-stone oratories favoured by early Irish monks for their meditation. Sitting aloft the island on a high terrace, commanding a panoramic view over the Atlantic Ocean in one direction and the fractal Kerry coast in the other, these simple stone cells came without windows – the business was one of prayer and meditation not horizon-gazing. Such isolation was necessary for reasons of both safety and spirituality. And Skellig Michael was the acme of isolation. In the early Christian milieu the Skellig Islands, facing the seemingly limitless Atlantic off the southwest coast of Ireland, were more than merely remote: they were at the very edge of the known world.

As the boat draws closer, the sheer volume of birds – gannets, fulmars, puffins, terns – becomes plain to see. With something like 70,000 birds, Little Skellig is the second largest gannet colony in the world. But on the larger island of Skellig Michael, although seabirds abound here too, there is also the suggestion of a human presence, albeit an historic one. High up in the rocks, small stone structures can be discerned: rounded domes that are clearly man-made and which soften the jagged silhouette of the island’s summit. These are beehive cells, the dry-stone oratories favoured by early Irish monks for their meditation. Sitting aloft the island on a high terrace, commanding a panoramic view over the Atlantic Ocean in one direction and the fractal Kerry coast in the other, these simple stone cells came without windows – the business was one of prayer and meditation not horizon-gazing. Such isolation was necessary for reasons of both safety and spirituality. And Skellig Michael was the acme of isolation. In the early Christian milieu the Skellig Islands, facing the seemingly limitless Atlantic off the southwest coast of Ireland, were more than merely remote: they were at the very edge of the known world. The island’s monastic site is infused with mystery, as all good ruins are, but is thought to have been established in the 6th century by Saint Fionán. Consisting of six beehive cells, two oratories and a later medieval church, the site occupies a stone terrace 600 feet above the swirling green waters of the sea below.

The island’s monastic site is infused with mystery, as all good ruins are, but is thought to have been established in the 6th century by Saint Fionán. Consisting of six beehive cells, two oratories and a later medieval church, the site occupies a stone terrace 600 feet above the swirling green waters of the sea below. Skirting Skellig Michael, a landing stage with a helicopter pad comes into view. A vertiginous path of stone steps leads up towards the beehive huts close to the island’s mountain-like summit. We do not disembark. Instead we keep sailing, bound for a safer harbour in Glengarriff in County Cork. No matter, the sight of the rocks, the winding, climbing path and the austere cells on the terrace at the top is already imprinted on our memory.

Skirting Skellig Michael, a landing stage with a helicopter pad comes into view. A vertiginous path of stone steps leads up towards the beehive huts close to the island’s mountain-like summit. We do not disembark. Instead we keep sailing, bound for a safer harbour in Glengarriff in County Cork. No matter, the sight of the rocks, the winding, climbing path and the austere cells on the terrace at the top is already imprinted on our memory. Without doubt this was a life of supreme hardship: the isolation, the relentless diet of fish and seabird eggs, the ever-battering wind and salt-spray. Such was the isolation, and so extreme the privations of this beatific pursuit, that one might assume that the monks would have been left in peace to practice their calling. This was not to be. Viking raiders arrived here in the early 9th century and took the trouble to land, scale the island’s heights and attack the monks. For most of us it is probably difficult to comprehend the blind-rage fury of the raiders, the wrath invoked in them by pious upstarts with their new Christian God. Easier perhaps is to imagine the dread that must have been felt by the monks as the Vikings approached their spiritual eyrie.

Without doubt this was a life of supreme hardship: the isolation, the relentless diet of fish and seabird eggs, the ever-battering wind and salt-spray. Such was the isolation, and so extreme the privations of this beatific pursuit, that one might assume that the monks would have been left in peace to practice their calling. This was not to be. Viking raiders arrived here in the early 9th century and took the trouble to land, scale the island’s heights and attack the monks. For most of us it is probably difficult to comprehend the blind-rage fury of the raiders, the wrath invoked in them by pious upstarts with their new Christian God. Easier perhaps is to imagine the dread that must have been felt by the monks as the Vikings approached their spiritual eyrie.

Pink

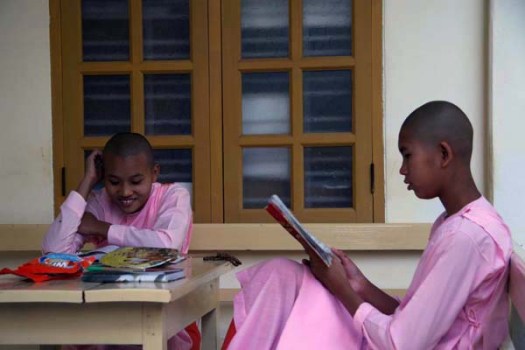

I will let the pictures do most of the talking in this post.

Buddhist nuns in Myanmar always dress in a fetching pink colour. A nun’s life is tough but they seem cheerful enough, collecting alms in the market, studying Pali sutras or sorting out clothes at the nunnery. The commitment is actually finite, as most Burmese girls only join the nunnery for a period of a few weeks at a time.

Buddhist nuns in Myanmar always dress in a fetching pink colour. A nun’s life is tough but they seem cheerful enough, collecting alms in the market, studying Pali sutras or sorting out clothes at the nunnery. The commitment is actually finite, as most Burmese girls only join the nunnery for a period of a few weeks at a time.

As with Burmese boys, time spent in monasteries is viewed as a right of passage and it is considered an honour for the family to have their child wear robes for even a short period. Naturally, it brings good karma too.

Young nuns at Mingun nunnery and at Amarapura market, Myanmar

The character below is actually a boy, despite the makeup and pink get-up. He is on his way to a monastery to become a monk for a few weeks. The boy is accompanied by villagers who sing stirring valedictory songs to him as he rides along on his pony. Most of the village seems to go along for the ride – it is a party atmosphere and drink (palm toddy perhaps) has certainly been taken by some of the happy entourage. Remarkable as it may seem, this is the sort of chance event that you stumble upon every day of the week in Myanmar.

Young novice processing to Buddhist monastery near Hpa-an, Myanmar

Young novice processing to Buddhist monastery near Hpa-an, Myanmar