Tucked away in the north Norfolk coastal hinterland, close to the villages of Overstrand and Northrepps, is a group of small ponds known as the Shrieking Pits. More of the same can also be found a few miles further west near Aylmerton close to Felbrigg Hall. Thought to be early medieval excavations for iron ore, the resultant pits have long been filled with water and softened by vegetation to allow them to blend in with the scenery as if they were natural features in this gentle post-glacial landscape.

Seeking them out, we made our way on foot from Overstrand, following the Paston Way inland through dark woodland and prairie-sized fields of barley and oilseed rape. The pits lie amidst arable land just beyond a farm at Hungry Hill, a name that points towards agricultural impoverishment at some time in the past. The pits stand beside a green lane, a byway of some antiquity that may have been here as long as the excavations themselves.

The first one we come across is small, surrounded by willows of a uniform height. In the ring of tree shade that encloses the shallow pond, a wooden palette left over from some undefined farming business lies next to the water liked an abandoned raft. The main ‘pit’ is nearby, an altogether larger and more impressive pond edged in by semi-recumbent oaks. The water is glassy and ink-black, suggesting great depth and perhaps a little menace. On the far bank the surface is coated with pond weed the colour of puréed peas. A small wooden notice board has been placed next to one of the oaks is but it is bare, its writing long gone to leave it devoid of information other than that which can be told by wood grain alone. Despite this unwitting redaction, a tangible sense of genius loci suggests that there is something to be told of this place other than a chance meeting of trees and water.

Naturally with a name like Shrieking Pit there is a strong likelihood of dark legend. The mundane answer is that the name alludes to the sound emitted by the exposed gravels. But does gravel really shriek? It scrapes and it crunches but does it make a noise quite so dreadful? Shriek is a loaded word, a term that evokes emotion – fear, dismay, even terror. It is these qualities that inform the folklore associated with the place.

The story goes that a grieving young woman haunts the locality. It tells of a heartbroken 17 year-old called Esmeralda who was seduced and then abandoned by a duplicitous local farmer. Inconsolable, the desperate young woman is said to have thrown herself into the water of the pit one dark night before immediately regretting her decision and crying for help that did not come. Her unheard cries are said to be heard at the spot each February 24th, the anniversary of her death.

Another story tells of a horse and cart vanishing without trace in the pool’s murky depths. Looking at the black unreflecting water it seems perfectly possible. Places such as this, although mere dust specks on the map, are the bread and butter of rural folklore. Such places inevitably become repositories of legend – features where the landscape can be painted with tales of intrigue, romance and horror. As the notice board is currently blank perhaps we should feel free to write our own story.

References:

http://www.heritage.norfolk.gov.uk/record-details?MNF6787-Shrieking-Pits

If trees could only speak. If they had some semblance of sentience and memory, and a means of communication, what would they tell us? Ancient trees – or at least those we suspect to be very old – are usually described in terms of human history. Perhaps as humans it is hubris that requires us to define them in this way but the fact is that by and large they tend to outlive us: many lofty oaks that stand today were already reaching for the sky when the Industrial Revolution changed the face of the land over two centuries ago. This linkage of history and old trees has resulted in some colourful local history. The story of the future King Charles II hiding from parliamentarian troops up a pollarded oak tree in Boscobel, Shropshire carried sufficient potency for the original tree to have been eventually killed by souvenir hunters excessively lopping of its branches as keepsakes. Undoubtedly the stuff of legend, Royal Oak ended up becoming the third commonest pub name in England. A long-established folk belief also tells of the Glastonbury Thorn, the tree which is said to have grown from the staff of Joseph of Arithmathea whom legend has it once visited Glastonbury with the Holy Grail. What was considered to be the original tree perished during the English Civil War, chopped down and burned by Cromwell’s troops who clearly held a grudge against any tree that came with spiritual associations or historical attitude.

If trees could only speak. If they had some semblance of sentience and memory, and a means of communication, what would they tell us? Ancient trees – or at least those we suspect to be very old – are usually described in terms of human history. Perhaps as humans it is hubris that requires us to define them in this way but the fact is that by and large they tend to outlive us: many lofty oaks that stand today were already reaching for the sky when the Industrial Revolution changed the face of the land over two centuries ago. This linkage of history and old trees has resulted in some colourful local history. The story of the future King Charles II hiding from parliamentarian troops up a pollarded oak tree in Boscobel, Shropshire carried sufficient potency for the original tree to have been eventually killed by souvenir hunters excessively lopping of its branches as keepsakes. Undoubtedly the stuff of legend, Royal Oak ended up becoming the third commonest pub name in England. A long-established folk belief also tells of the Glastonbury Thorn, the tree which is said to have grown from the staff of Joseph of Arithmathea whom legend has it once visited Glastonbury with the Holy Grail. What was considered to be the original tree perished during the English Civil War, chopped down and burned by Cromwell’s troops who clearly held a grudge against any tree that came with spiritual associations or historical attitude. There is an ancient thorn in Norfolk that is sometimes connected with the same Joseph of Arithmathea myth. Hethel Old Thorn can be found along narrow lanes amidst unremarkable farming country 10 miles south of Norwich. Close to the better known

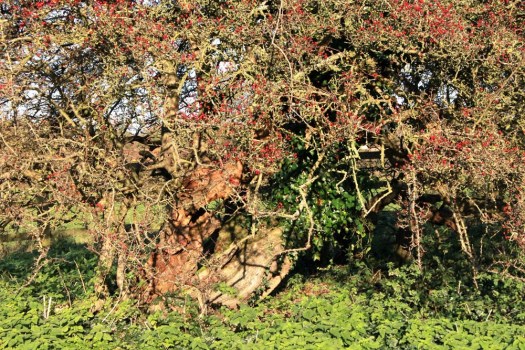

There is an ancient thorn in Norfolk that is sometimes connected with the same Joseph of Arithmathea myth. Hethel Old Thorn can be found along narrow lanes amidst unremarkable farming country 10 miles south of Norwich. Close to the better known  At an estimated 700 years old this is thought to be the oldest specimen of Crataegus monogyna in the UK. Like the nearby Kett’s Oak, the thorn was thought to be a meeting place for the rebels during

At an estimated 700 years old this is thought to be the oldest specimen of Crataegus monogyna in the UK. Like the nearby Kett’s Oak, the thorn was thought to be a meeting place for the rebels during