The best of India is often seen in the slow hours before breakfast, the time of day when the subcontinent’s multitude of people and gods stir themselves in the cool mercury light that follows dawn.

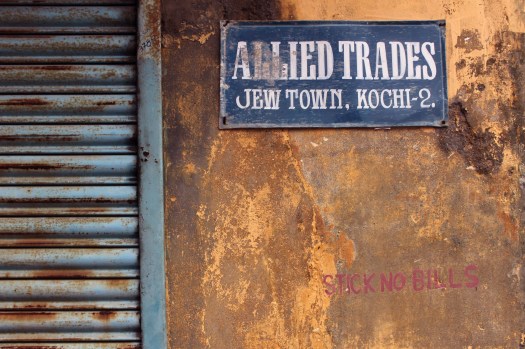

On my last day in India I rose early to retrace steps from a walk I had made the day before. Down to the Mattancherry shore, to the narrow streets of the area known as Jew Town, a small waterside enclave of the port city of Kochi. The name was self-explanatory, although very few Jews now lived in the vicinity as most had left for a new life in Israel in the 1940s.

In the midday heat of the previous day there had been the usual noise and mayhem, the customary bluster that accompanied daily life in any Indian city: pavements blocked with vendors and parked motorbikes, auto rickshaws tuk-tuk-ing incessantly up and down as their drivers looked for fares and nonchalantly swerved around any pedestrian foolish enough to get in their way. Jew Town lay next to the shore, beyond the compound of Mattancherry Palace. A gently touristified quarter of souvenir shops, Kashmiri-run gift emporia and restaurants serving the appetizing alchemy of rice, coconut and spices that was Keralan cuisine, there were few reminders that this quarter of the city was historically Jewish apart from a pristine, albeit virtually redundant, 16th-century synagogue.

The sun had barely risen above the coconut palms and low-rise stucco of Fort Cochin as I set off down Mattancherry Palace Road. Even at this early hour the Hindu temple on the corner was buzzing with activity, with bare-chested drummers welcoming a procession led by a dhoti-clad priest clutching an offering of fragrant flowers in a coconut half. Most of the businesses that lined the road were still shuttered but a few shopkeepers were already at work outside their premises brushing the pavement in preparation for the day ahead. There was little traffic apart from a few cyclists determinedly peddling somewhere. Whether they were on their way to work, or perhaps heading home after a night shift, there was no way of knowing. In modern India motorbikes are the preferred means of transport for those wealthy enough to afford one yet here in Kochi it seemed that bicycles still had an important role to play.

I passed a lorry being emptied of its load of bananas on a side street. It was hard to imagine life here in Kerala without bananas. Or, even more essentially, coconuts, whose flesh and milk flavoured almost every meal, whose oil glistened in most women’s hair, whose swaying palms cooled almost every street. Every street, that is, apart from those close to the shore, where ancient rain trees cast huge penumbras of shade – massive, branching moss-hung trees that looked like as if they had been directly transplanted from a rainforest.

Curiosity led me down another inviting side street but after about five minutes it ended abruptly and so I turned around to return to the main road to continue east towards the water. I soon reached Mattancherry Palace and skirted its grounds along a road that took me past a jail, a newly built mosque and a post sorting office. This curved round to reach the main waterside drag of Jew Town Road. On my previous visit the road had been busy with gift shops, souvenir hawkers and sunburned tourists coached-in from coastal resorts. At this early hour, though, it was a very different place, a somnolent neighbourhood where the stalls were unmanned, the coach park empty, the touts still deep in slumber. In the sprawling branches of rain trees above the road white egrets were perched in anticipation of the free meal that might come later when the food stalls were set up for business. Below them on the electricity wires pigeons had spread themselves out like notes on the stave – a serendipitous score for a morning raga.

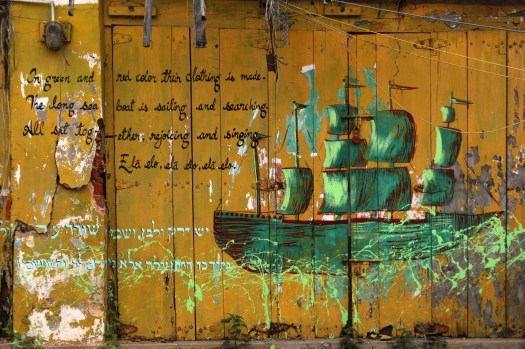

I wandered down to a deserted quay to get a view to Willingdon Island across the water. Faded remnants of advertising were still visible on some of the walls although a ferry had not run from here for years. Back on the main street I walked south through the small tourist enclave into an altogether more quotidian world that declined in prosperity as I continued. What had once been a prosperous Jewish neighbourhood had since become a less affluent Muslim one. Cavernous godowns – spice warehouses – lay behind peeling sky-blue doors. A few were still operating as such while others had been given over to businesses like motorcycle repair workshops. Some of the walls had been painted with colourful murals – public art with text in Hebrew and curling Malayalam script that celebrated Kochi’s maritime heritage. One building that caught my attention had an open entrance behind a pile of rubble. Inside a half-collapsed porch stood another portal, a ragged blue cloth dangling in the space where a door would once have been. It was a synagogue – or what remained of one – its roof aerated by enough missing tiles to allow light and rainwater to penetrate the interior, a void filled with broken bricks, rotting beams and a thick carpet of guano. The throat-searing ammoniacal stench of pigeon shit was so overwhelming that mere inhalation felt hazardous. This sorry wreck of a building was a long way from the lovingly maintained Paradesi Synagogue I had witnessed the day before – the officially sanctioned tourist sight just up the road beyond the gift shops. Here in this neglected, unloved ruin the sense of wholesale abandonment of a community was tangible: here was a place whose ghosts whispered of sorrow and loss.

One way of looking at this evocative, if mildly disturbing, place is as a hidden enclave populated with the ghosts of colonialism. Situated right in the middle of Kolkata, tucked away purdah-like from the mayhem of the city streets, the Park Street Cemetery seems like another world. It really is another world: one in which time has coalesced to leave a thick patina on the colonnades and obelisks that commemorate the colonists who created this tropical city in their own image. The colonials mostly died young – easy victims of the disease-ridden, febrile climate that characterised this distant outpost of the East India Company. In true Victorian manner, those who were unfortunate enough to die young and never be able to return to their temperate homeland were interred here in magnificent mausoleums among lush, very un-British vegetation – a tropical Highgate transposed a quarter-way round the world. The cemetery is reputed to be the largest Old World 19th-century Christian graveyard outside Europe. It is also one of the earliest non-church cemeteries, dating from the 1767 and built like much of Kolkata/Calcutta on low, marshy ground. The overall effect is one of Victorian Gothic, although there are also some notable flourishes of Indo-Saracenic vernacular that reflect the influence of Hindu temple architecture.

One way of looking at this evocative, if mildly disturbing, place is as a hidden enclave populated with the ghosts of colonialism. Situated right in the middle of Kolkata, tucked away purdah-like from the mayhem of the city streets, the Park Street Cemetery seems like another world. It really is another world: one in which time has coalesced to leave a thick patina on the colonnades and obelisks that commemorate the colonists who created this tropical city in their own image. The colonials mostly died young – easy victims of the disease-ridden, febrile climate that characterised this distant outpost of the East India Company. In true Victorian manner, those who were unfortunate enough to die young and never be able to return to their temperate homeland were interred here in magnificent mausoleums among lush, very un-British vegetation – a tropical Highgate transposed a quarter-way round the world. The cemetery is reputed to be the largest Old World 19th-century Christian graveyard outside Europe. It is also one of the earliest non-church cemeteries, dating from the 1767 and built like much of Kolkata/Calcutta on low, marshy ground. The overall effect is one of Victorian Gothic, although there are also some notable flourishes of Indo-Saracenic vernacular that reflect the influence of Hindu temple architecture.  Arriving at the gatehouse my name is recorded in a ledger by a lugubrious guard, an action that in itself carries the hint of entering some sort of forbidden zone, a place where the living are only tolerated and should not outstay their welcome. The cemetery seems largely deserted of visitors, although I do inadvertently stumble across a spot of surreptitious man-on-man action taking place in the deep shade of one of the tombs. Despite the funerary setting, there is nothing occult at work here, and I conclude that the young men are simply taking advantage of the privacy offered by the cemetery in this most crowded of all India’s overflowing mega cities. There are signs prohibiting ‘committing nuisance’ attached to some of the trees and I wonder if this is a warning against this sort of clandestine liaison, although in India the expression is usually a euphemism for public urination.

Arriving at the gatehouse my name is recorded in a ledger by a lugubrious guard, an action that in itself carries the hint of entering some sort of forbidden zone, a place where the living are only tolerated and should not outstay their welcome. The cemetery seems largely deserted of visitors, although I do inadvertently stumble across a spot of surreptitious man-on-man action taking place in the deep shade of one of the tombs. Despite the funerary setting, there is nothing occult at work here, and I conclude that the young men are simply taking advantage of the privacy offered by the cemetery in this most crowded of all India’s overflowing mega cities. There are signs prohibiting ‘committing nuisance’ attached to some of the trees and I wonder if this is a warning against this sort of clandestine liaison, although in India the expression is usually a euphemism for public urination.  There are, of course, those who take full advantage of the cemetery’s concentrated occult power – fakirs who use it for training apprentices by making them spend the night here alone, an experience that could never be a comfortable one however much one was inured to the idea of djinns being hyperactive after dark. Even for hard-nosed rationalists, the sense of the numinous here is quite tangible, and the cemetery is without doubt a thoroughly spooky place. This is true even in broad daylight when the taxi horns and traffic thrum from the manic thoroughfare of Mother Teresa Sarani (formerly Park Street; before that, Burial Ground Road) cuts through the trees to provide a background drone for the tuneless squawks of the urban crows and parakeets that loiter here.

There are, of course, those who take full advantage of the cemetery’s concentrated occult power – fakirs who use it for training apprentices by making them spend the night here alone, an experience that could never be a comfortable one however much one was inured to the idea of djinns being hyperactive after dark. Even for hard-nosed rationalists, the sense of the numinous here is quite tangible, and the cemetery is without doubt a thoroughly spooky place. This is true even in broad daylight when the taxi horns and traffic thrum from the manic thoroughfare of Mother Teresa Sarani (formerly Park Street; before that, Burial Ground Road) cuts through the trees to provide a background drone for the tuneless squawks of the urban crows and parakeets that loiter here.  Not requiring of any such thaumaturgic rite of passage, a short afternoon visit suits me just fine. I am left alone with just the crows for company – dark portentous forms that swirl and scatter in the trees above, occasionally coming down to perch scurrilously on the sarcophagi as if they were extras from an Edgar Allen Poe film adaptation. Indeed, this would be the perfect location for a Gothic horror film, especially one that required a steamy colonial setting. Park Street Cemetery is the sort of place where dead souls rising from the ground can seem a distinct possibility – an eerie realm where the hubris of the Raj confronted its own vulnerability and the sad ghosts of empire still linger.

Not requiring of any such thaumaturgic rite of passage, a short afternoon visit suits me just fine. I am left alone with just the crows for company – dark portentous forms that swirl and scatter in the trees above, occasionally coming down to perch scurrilously on the sarcophagi as if they were extras from an Edgar Allen Poe film adaptation. Indeed, this would be the perfect location for a Gothic horror film, especially one that required a steamy colonial setting. Park Street Cemetery is the sort of place where dead souls rising from the ground can seem a distinct possibility – an eerie realm where the hubris of the Raj confronted its own vulnerability and the sad ghosts of empire still linger.

![2010331144160.9781841623214100[1]](https://eastofelveden.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/2010331144160-978184162321410012.jpg?w=93&h=150)