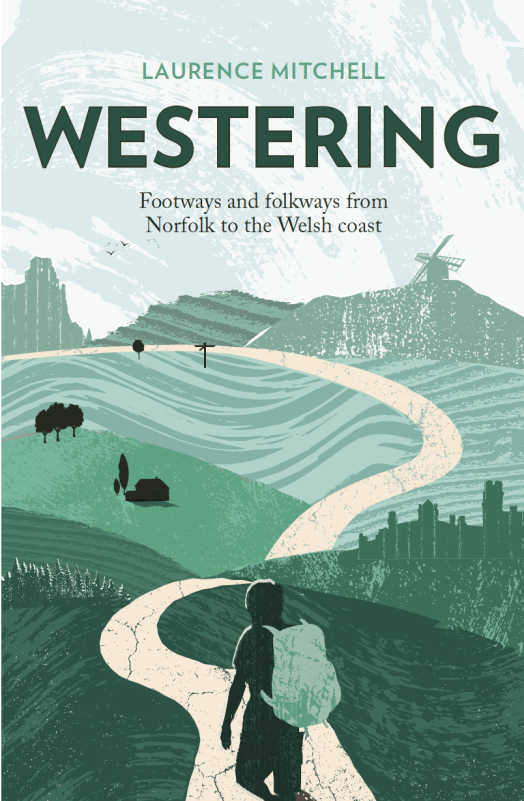

My book Westering is published this week by the award-winning independent publisher Saraband. Beginning in Great Yarmouth and meandering to Aberystwyth, the book describes a coast-to-coast journey on foot traversing the Fens, East Midlands, Birmingham, the Black Country and central Wales.

Here is a brief extract from the first chapter. It should be noted that the accompanying photographs shown here are NOT included in the book.

Extract from Chapter 1: Red Herrings

From our high viewpoint it was clear that Yarmouth developed on a sand spit, a narrow finger of land squeezed between the North Sea and the River Yare that points accusingly southwards in the direction of Lowestoft. Modern housing and light industry have long filled in the space between the river and the sea, and an industrial estate now surrounds the base of the column, but when the monument was first erected in the second decade of the 19th century, to commemorate Nelson’s maritime victories, it stood alone on a fishing beach, isolated from the town to the north.

Looking south, we could see the mouth of the River Yare at Gorleston. Just beyond were the Suffolk border and a cluster of holiday villages before the sprawl of Yarmouth’s historic rival, Lowestoft, Britain’s most easterly town. Further south still was the prim resort of Southwold, which, like its neighbours Dunwich and Walberswick, was once a mighty port before silting and coastal erosion took their toll. To the east lay the taut curve of the North Sea – a wave-flecked, grey-green expanse that diminished to a hazy vanishing point. A cluster of wind turbines, their blades almost immobile on this calm late-summer day, stood someway offshore at Scroby Sands. Across the water, far beyond the horizon, unseen even from our elevated viewpoint, were the polders and dykes of the Netherlands, a country that once had close economic ties with this easternmost part of England.

Some impulse had me imagining a time before the rising sea levels that followed the last glacial period, a time when a land bridge still connected Britain to Europe. Doggerland, as the territory has become known, now lies beneath the waves but it was a land of plenty just a few thousand years ago, roamed by mammoths, bison and small bands of Mesolithic hunters.

A little way beyond the entrance to Wellington Pier stands the intricate Victorian wrought-iron framework of the Winter Gardens, the last remaining building of its type in the country. Impressive but now empty and neglected, the structure resembles a giant multi-storey conservatory in need of a paint job: a potential future Eden Project in waiting (this is still one council member’s dream), if only the necessary funding could be raised. Although it looks perfectly at home here on the North Sea coast, the building was a blow-in from the southwest. Originally constructed in Torquay, it stood in that resort for twenty-four years before being carefully dismantled and barged around the coast in 1903 to take up residence here alongside Yarmouth’s then brand-new Wellington Pier.

Across the road from the Winter Gardens, the Windmill Theatre has a facsimile set of sails attached to its façade in impersonation of the Moulin Rouge in Paris, although it is doubtful if the floor show here was ever quite as racy as its French equivalent. Back in the 1950s, this building – which started life as The Gem, the country’s first electric picture house – hosted George Formby summer residencies. The Norfolk coast and the nearby Broads had become a second home for Formby in his twilight years when, rather than old-fashioned variety, public taste was starting to demand a more exciting, rock n’ roll flavour for its entertainment. But the entertainer and his ukulele always had a loyal following here on the Norfolk coast, where tastes were more down to earth. It did not take much imagination to turn the clock back to Yarmouth’s heyday and picture a grinning, Brylcreemed Formby strolling along this very same seafront in pullover and baggy flannels as he dreamed up double-entendres in the briny air.

Much of the Yarmouth that would have been familiar to Formby is still evident: the beach, the town’s ‘Golden Mile’ of amusement arcades, the miniature golf courses and pleasure gardens, the fast food outlets that gift the seafront a pungent cocktail of chip fat and fried onions (with notes of biodegraded phytoplankton from the beach and horse shit from the pony-drawn landaus). Such attributes are not as popular as they once were, but the town’s latter-day decline is the familiar story of many English seaside resorts in the late 20th century. The beach is still as pristine as ever, but a number of the town’s once-flourishing entertainment palaces now lie empty and abandoned. The Empire was one such place, a former theatre that lacked both audience and, until recently, a full complement of letters above its art nouveau doorway, its former terracotta cladding stripped and once-proud colonial name reduced by weathering and gravity to read ‘EMPI’. Although touted by some as an ideal venue for a future art gallery, it still stands empty and unloved.