Of all London’s lost rivers it is the Walbrook that is the most irrefutably lost: lost to time, lost to place… well, almost. An important source of water in Roman times, when its banks were lined with the workshops of Roman industry – tanneries, potteries and glass workshops – the river has not been visible on the surface since the 15th century when the last open sections were vaulted over. Ghosting the boundary of Roman London, its confluence with the Thames lay close to what is now Cannon Street Station Bridge. Where the Walbrook began is less certain, although what is clear is that its course flowed between the City of London’s two principle hills – Ludgate and Cornhill. Some say its source was a spring close to what is now Shoreditch High Street, while others point to higher ground at Islington.

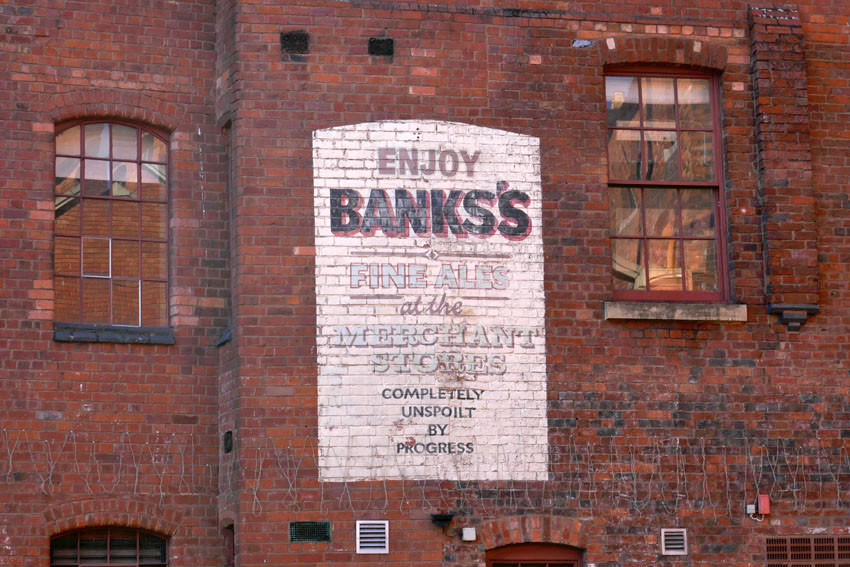

Lost to time, perhaps, but there clues to place – in street names, in signs, in places of worship, in the Roman street plan. The walking route tracing the Walbrook’s course that I describe here is faithful to that given in Tom Bolton’s excellent London’s Lost Rivers: a Walker’s Guide Volume 1.

I begin on Curtain Road that runs south from Shoreditch. Holywell Road that abuts it to the east is an intimation of the location of the aforementioned spring. Curtain Street leads to Appold Street and through Broadgate Circle, an upmarket shopping and leisure hub that until 1984 served as a railway station and which was formerly a burial ground for the Bethlehem Royal Hospital, better known as Bedlam. It also served as a mass grave for victims of the various bubonic plague outbreaks in pre-Fire London – grim, no doubt, but dig down almost anywhere in central London and you will find human bones sooner or later. The River Walbrook would have passed through here before flowing along what is now Bloomfield Street to reach the Roman-built London Wall, which served as the boundary of the City until the 18th century. The Walbrook is believed to have flowed through a hole in the wall at an aqueduct close to where Bloomfield Street meets the Wall.

Channelling the disappeared river, I pass through elegant iron gates of the Wall into Throckmorton Avenue, then turn right and left into an alleyway opposite a barber’s shop that seems incongruous amidst all this high-rise estate of capital. But even financiers need to be shaved and shorn occasionally – sharp haircuts and a regular supply of barista coffee are the basic necessities of life in the City. The alleyway leads into to the narrow passageway of Tokenhouse Yard, at the end of which is the reflected light of the north wall of the Bank of England, the building’s Portland stone preternaturally aglow in the gloom of an overcast November day. The magnetic pull of capital here is almost spiritual: money buys, Jesus saves, sinners spend. Sir John Soane, the Bank of England architect, surveys the scene from his statue recessed high into the wall, while the ghost of the river traverses beneath the building, symbolically moistening – perhaps laundering – the horded lucre in the vaults beneath.

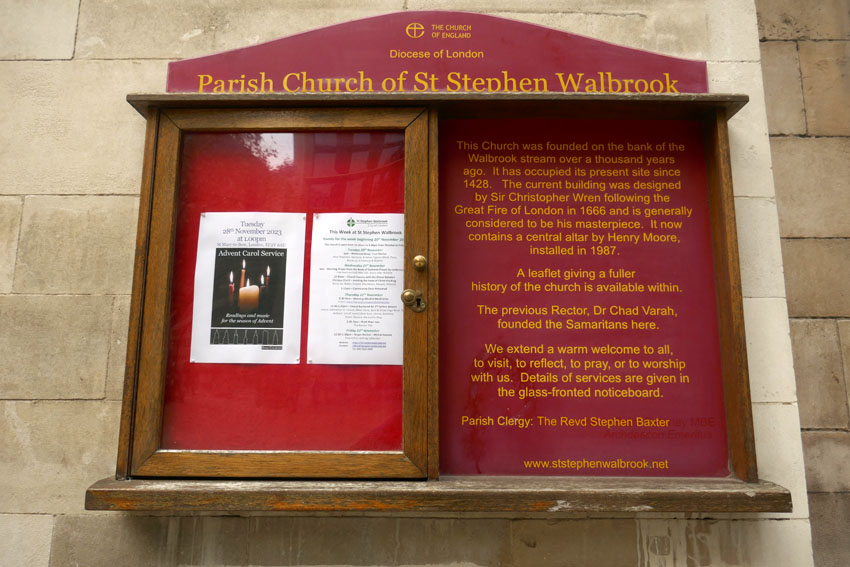

Riverwards, beyond the Bank, lies the Church of St Stephen’s Walbrook and a street of the same name. The elusive river is acknowledged at last. The church, originally situated on the bank of the Thames, was moved here in the 14th century. The Walbrook would have flowed just west of here. The street is dominated by the block-length, Norman Foster-designed Bloomberg building, which has an undulating profile that hints at the vanished river. On its ground floor, an etched glass door leads into the London Mithraeum, a museum dedicated to the Mithras temple that once stood on the banks of the Walbrook nearby. A place where Mithras and Bacchus were once worshipped by Roman soldiers, Mammon has since taken over as chief deity on this patch of expensive real estate.

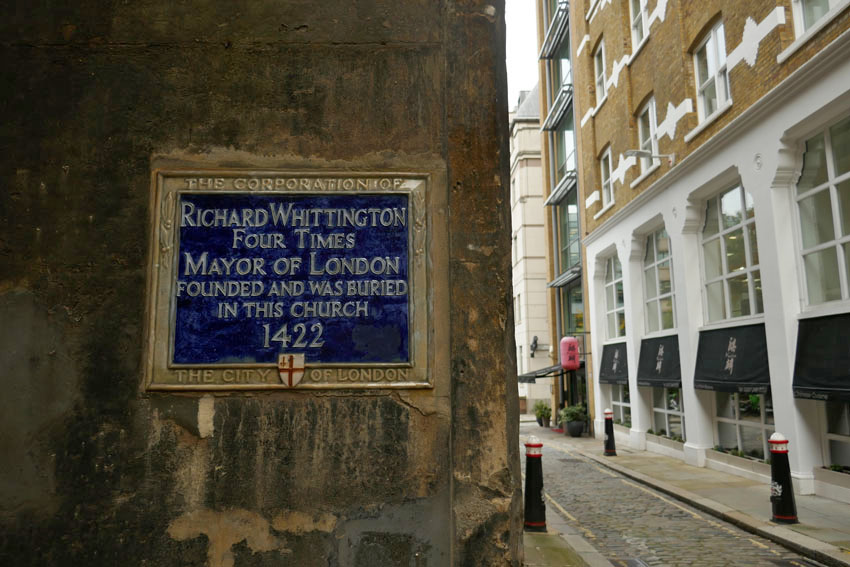

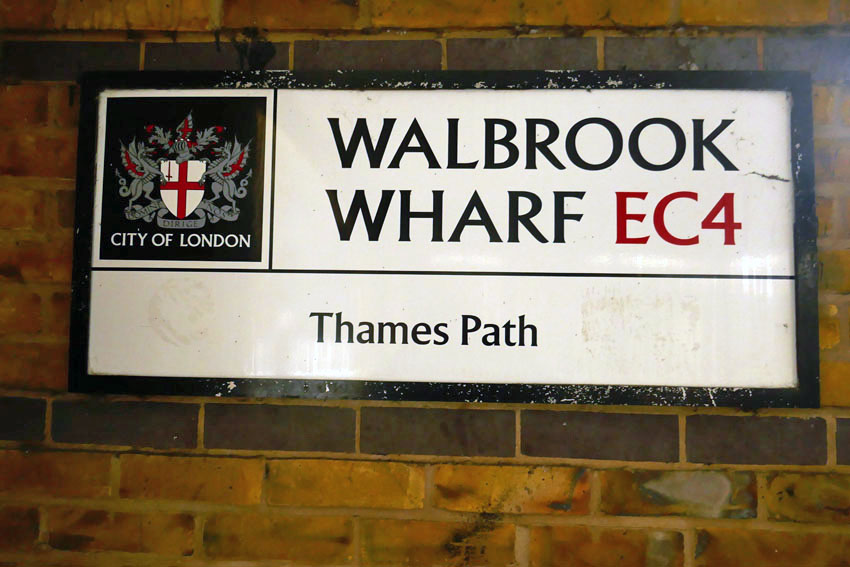

Just south of here, within sight of Cannon Street Station, is the Church of St Michael Paternoster Royal. Alongside are Whittington Gardens, named after the famous cat-loving, four-time Lord Mayor of the city who is buried here. This was the original location of confluence of the Walbrook with the Thames – the mighty river has shifted south in the two millennia that has passed since Roman times. Upper Thames Street now flows with traffic where once the tidal river lapped. The modern confluence, theoretical as it may be, lies not far away along Cousin Lane, a narrow street that traces the long wall of Cannon Street Station down to the railway bridge over the Thames. Here there is a pub and steps leading down to the water. There is also a river path that leads west along Walbrook Wharf, where black barges lie tilted on the shore awaiting the incoming tide.

The tide is out and so I descend to the beach, which is covered with assorted pebbles, water-blunted bricks and a few rusted scraps of iron. Scattered among the pebbles, a small piece of pottery reveals itself at my feet – curved, brown; reassuringly rustic. Roman? Who knows, probably not, but somehow it feels right. A votive offering – it marks the place where London began.