The very mention of the village of Happisburgh in Norfolk brings to mind all manner of prehistoric associations and connections with long-extinct ancestors. The early years of this current century have revealed exciting local evidence of the presence of earliest hominins in northwest Europe: Homo antecessor (‘Pioneer Man’) – near million-year-old clues in the form of flint tools and muddy footprints. Early humans walked these shores in the early Pleistocene, except it wasn’t so much a shore then as a river estuary: the Thames in an earlier incarnation when it flowed further north than its current course. Political boundaries were yet to exist, 800,000 years ago; the land mass that was Britain was still connected to Eurasia.

Prehistory aside, Happisburgh (pronounced ‘Haze-bruh’ to those who know) is also well known for other reasons. Its fame precedes it, although notoriety might be a better term. Nowhere on this coastline is the menace of coastal erosion witnessed more emphatically, although the near-vanished village of Dunwich on the Suffolk coast, once a thriving medieval port, might come close. For Dunwich the damage wreaked by the ever-invading North Sea is the past; in Happisburgh it is the present and future. Continually losing territory to the North Sea, there is visible evidence of the dynamic shifting shoreline to be seen everywhere here. Cliffs can be witnessed crumbling on a regular basis. Houses that were once located comfortably inland now perch perilously close to cliff edges; some have already succumbed and their remains litter the beach. Roads and tracks can be seen dramatically truncated along the cliff edge – streets that have become roads to nowhere, roads that lead to oblivion.

Even the village’s longstanding icons – the 15th-century St Mary’s church with its commandingly tall tower, the second highest in the county, and the equally imposing red-banded Trinity lighthouse built in 1790, Norfolk’s oldest – are both numbered in their days and probably won’t see this century out. The writing has been on the wall for a long time now – this northwest stretch of the Norfolk littoral is, after all, a fast-eroding coastline where such things can only be expected. Even so, the terrifying spectre of irreversible climate change does nothing but hasten the inevitable. Bold efforts have been made to ameliorate the threat: large chunks of alien geology have been transported here to be deposited on the beach – stone barriers to hold back the tide – yet somehow it feels like the wrong sort of folk tale: a village boy taking up a slingshot against a giant ogre, a near-futile King Cnut-like gesture.

So, there is plenty to say about Happisburgh but what of Ostend, its immediate neighbour to the north? Walking the coast here recently in preparation for a new book on short walks in Norfolk, I tried to find out more about the small settlement that shares its name with the better known Belgian resort. Information was elusive, other than it belonged to the parish of Walcott and was effectively an area of holiday properties appended to the south of that village. The name intrigued me, though, and I wondered whether there was a historical connection as there are several Waterloo farms scattered around Norfolk that commemorate the final victory over Napoleon close to the Belgian town of that name. Until 2001, when it was finally demolished, there used to be an early 17th century house in the village was called Ostend House. There may possibly be a connection here but was it always called Ostend House, or did the name come with the rebuild that took place in the 19th century?

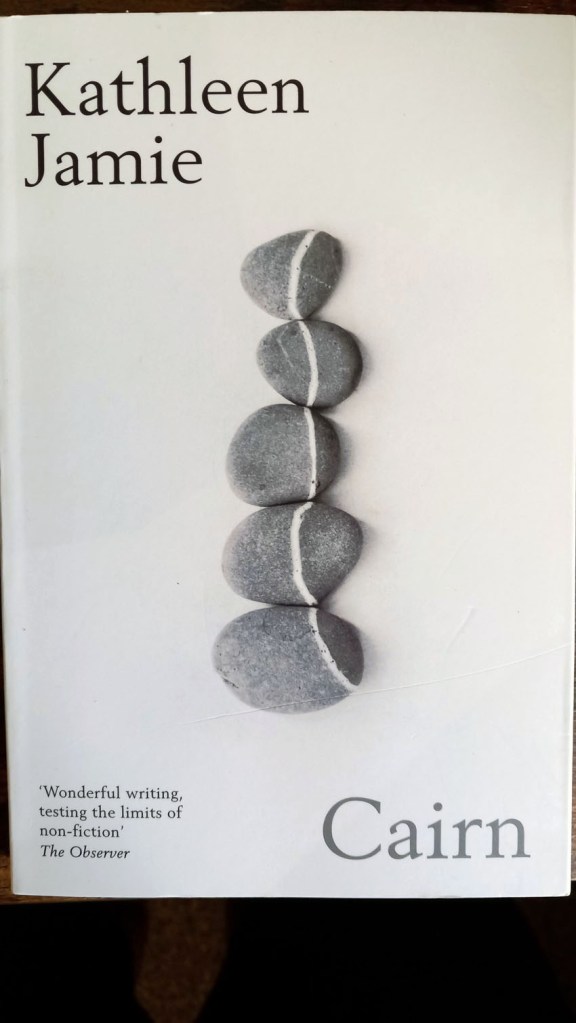

Looking further for information, Wikipedia informed me that in June 2002 a rare Cuvier’s beaked whale was stranded on the beach here. This was the same species of whale that Kathleen Jamie describes being on display in Bergen’s Whale Museum. The Bergen whale was found choked by plastic bags that the unfortunate animal had probably mistakenly recognised as squid, its prime food source. As I had only just (twice) read Jamie’s latest book Cairn,which describes her return visit to the Norwegian museum, there was an immediate connection for me here, although it was nothing to do with the name of the place.

The whale was named by the French scientist Georges Cuvier (1769—1832)*, a polymath who was the first to coin the term ‘extinction’. In 1796 Cuvier presented a paper to the National Institute of Science and Arts in Paris, where he compared the anatomy of living and fossil elephants to prove that extinction was a fact and proposed that the now-extinct elephants had been wiped out by periodic catastrophic flooding events. Although a proponent of catastrophism in geology, Cuvier rejected the idea of organic evolution. As an essentialist he believed that plants and animals were created for particular roles and niches in the world environment and subsequently remained unchanged throughout their existence. In Cuvier’s thinking, as soon as one species became extinct as the result of geological upheaval, another would be divinely created to replace it. It would be Charles Darwin, of course, who would set the record straight some 65 years later with the publication of his On the Origin of Species. What Darwin would have made of the 21st-century discovery of evidence of a long-extinct ancestor, Homo antecessor, on a sea-battered English shoreline we can only imagine. Evolution to extinction: such a surprisingly short distance of time and space linking the two.

*[Alas, Cuvier’s name has also been linked with scientific racism, although we might excuse him for being, as the cliché goes, ‘a man of his time’. Of course, modern-day racists should not be forgiven in the same way – they are not men (or women) of their time. We might, I suppose, call them dinosaurs but to do that would be a disservice to palaeontology.]

I set out from Kessingland, just south of Lowestoft, where a large expanse of dunes and shingle separates the sea from the holiday homes and caravans that line the low clifftop like racing cars at a starting grid preparing to rush towards the sea. Truth be told, there is little in the way to stop them. It may be August but even now the beach is relatively quiet – just a few families and dog-walkers clambering over the dunes to reach the sea, which today is grey, grumpy and not particularly welcoming. The Kessingland littoral is distinguished by its specialist salt-tolerant flora: sea holly, sea pea, sea campion, sea beet – in fact, place a ‘sea’ in front of any common plant name and there is a good chance that such a species will exist and flourish here. Also rooted into the shingle, thriving on little more than sunshine and salt spray, are clumps of yellow-horned poppies with long twisting seed pods. The poppies are mostly past their flowering peak but elsewhere, where there is a thin veneer of soil to root into, colour is provided by stands of rosebay willow herb – a rich purple layer of distraction between the straw-hued shingle and the cloud-heavy sky, both washed of colour in the flat coastal light.

I set out from Kessingland, just south of Lowestoft, where a large expanse of dunes and shingle separates the sea from the holiday homes and caravans that line the low clifftop like racing cars at a starting grid preparing to rush towards the sea. Truth be told, there is little in the way to stop them. It may be August but even now the beach is relatively quiet – just a few families and dog-walkers clambering over the dunes to reach the sea, which today is grey, grumpy and not particularly welcoming. The Kessingland littoral is distinguished by its specialist salt-tolerant flora: sea holly, sea pea, sea campion, sea beet – in fact, place a ‘sea’ in front of any common plant name and there is a good chance that such a species will exist and flourish here. Also rooted into the shingle, thriving on little more than sunshine and salt spray, are clumps of yellow-horned poppies with long twisting seed pods. The poppies are mostly past their flowering peak but elsewhere, where there is a thin veneer of soil to root into, colour is provided by stands of rosebay willow herb – a rich purple layer of distraction between the straw-hued shingle and the cloud-heavy sky, both washed of colour in the flat coastal light.  Further south, the cliffs grow a little higher. Ferrous red and as soft and powdery as halva, they are irredeemably at the mercy of the North Sea tide. And it shows: the cliffs are raw and freshly cleaved, with collapsed chunks that have been further eroded by the incoming tide such that they appear to seep from the cliff bases like congealed gravy. Man-made objects receive no preferential treatment – a collapsed WWII concrete defence bunker slopes between cliff and sand at one point, its long process of total disintegration still in its infancy as its perches ignominiously at 45 degrees, an involuntary buttress for the flaking cliffs.

Further south, the cliffs grow a little higher. Ferrous red and as soft and powdery as halva, they are irredeemably at the mercy of the North Sea tide. And it shows: the cliffs are raw and freshly cleaved, with collapsed chunks that have been further eroded by the incoming tide such that they appear to seep from the cliff bases like congealed gravy. Man-made objects receive no preferential treatment – a collapsed WWII concrete defence bunker slopes between cliff and sand at one point, its long process of total disintegration still in its infancy as its perches ignominiously at 45 degrees, an involuntary buttress for the flaking cliffs.