In contrast to the northwest Scotland of previous posts, the central Siberian city of Tomsk is indisputably East of Elveden – both figuratively and geographically. It is, after all, almost one quarter of the way around the world heading east from where I write. I spent a few grey rainy days here last autumn as a side trip to a long Trans-Siberian rail journey.

In contrast to the northwest Scotland of previous posts, the central Siberian city of Tomsk is indisputably East of Elveden – both figuratively and geographically. It is, after all, almost one quarter of the way around the world heading east from where I write. I spent a few grey rainy days here last autumn as a side trip to a long Trans-Siberian rail journey.

Tomsk lies just north of the main Trans-Siberian line, a sizeable city of about half a million sitting on the right bank of the Ob, a river that snakes its way north from here to the Gulf of Ob and the Arctic Ocean. Tomsk isn’t Arctic though – it lies at about the same latitude as Moscow and Glasgow, although it does drop to less than −20 °C in winter. Back in the 19th century, Tomsk was populated mostly by Cossacks, Tatars and political exiles but the city was side-stepped during the building of the Trans-Siberian railway line, when the new city of Novosibirsk (‘New Siberia’) was favoured as a stop instead.

These days Tomsk is a youthful, student-filled city; a relatively attractive place by Siberian standards, with a clutch of trendy brightly lit cafes around Ploschad Lenin, its central square. Trendy coffee bars are all the rage in the new Russia – even in backwoodsy Siberian cities like Tomsk. Here you’ll find ‘Travellers Coffee’, where you can get a pricey ‘bolshoi’ cappuccino, and another place called ‘Food Master’ – in a land where the Cyrillic alphabet reigns supreme, Latin script and English names are considered a guarantee of Western sophistication… or cheerless fast food. Food Master dishes up Mexican food with a pronounced Siberian accent – fajitas with beetroot, refried beans with dill and so on. There’s also an awkwardly translated English menu that temptingly offers ‘Languages with mushroom sauce’ and ‘Fat lard’ – fusion cuisine perhaps, but with a ‘con-’ prefix. Even here, in an establishment that is unapologetically ‘New Russia’, a Soviet-era fixation persists that has each component priced according to weight and itemised on the final bill – bread (the precise number of slices), sauce, garnish, meat (again precise, eg: ‘pig meat, 100g’) – as it would be the humblest factory workers’ stolovaya canteen. Actually, stolovayas are the places that I generally try and seek out – redolent of boiled cabbage, they promise cheap wholesome stodge served up by plump headscarfed women – just point and smile (or scowl if you want to blend in). It’s a genuine retro experience: school dinners, Soviet style. There is one of these tucked away in a basement a little further along Prospekt Lenin.

These days Tomsk is a youthful, student-filled city; a relatively attractive place by Siberian standards, with a clutch of trendy brightly lit cafes around Ploschad Lenin, its central square. Trendy coffee bars are all the rage in the new Russia – even in backwoodsy Siberian cities like Tomsk. Here you’ll find ‘Travellers Coffee’, where you can get a pricey ‘bolshoi’ cappuccino, and another place called ‘Food Master’ – in a land where the Cyrillic alphabet reigns supreme, Latin script and English names are considered a guarantee of Western sophistication… or cheerless fast food. Food Master dishes up Mexican food with a pronounced Siberian accent – fajitas with beetroot, refried beans with dill and so on. There’s also an awkwardly translated English menu that temptingly offers ‘Languages with mushroom sauce’ and ‘Fat lard’ – fusion cuisine perhaps, but with a ‘con-’ prefix. Even here, in an establishment that is unapologetically ‘New Russia’, a Soviet-era fixation persists that has each component priced according to weight and itemised on the final bill – bread (the precise number of slices), sauce, garnish, meat (again precise, eg: ‘pig meat, 100g’) – as it would be the humblest factory workers’ stolovaya canteen. Actually, stolovayas are the places that I generally try and seek out – redolent of boiled cabbage, they promise cheap wholesome stodge served up by plump headscarfed women – just point and smile (or scowl if you want to blend in). It’s a genuine retro experience: school dinners, Soviet style. There is one of these tucked away in a basement a little further along Prospekt Lenin.

Stylish cafes are not the only concession to Western culture. Halfway along the high street a gable is covered with an enormous poster of gravel-voiced American troubadour Tom Waits standing astride a railway line and bellowing into a microphone windscreen mounted on a crooked stick – very much Tom the iconic hobo poet. The club in the basement beneath is called ‘Underground’ (a song from Swordfishtrombones) and, of course it is a lovely pun – Tom(sk) Waits – geddit. It seems unlikely that Tom Waits’ management is aware of this brazen Siberian deployment but equally doubtful that Californian copyright law stretches quite this far. Waits is well known as an enthusiastic litigator of those who besmirch his image but this one seems to fit the brand perfectly.

Stylish cafes are not the only concession to Western culture. Halfway along the high street a gable is covered with an enormous poster of gravel-voiced American troubadour Tom Waits standing astride a railway line and bellowing into a microphone windscreen mounted on a crooked stick – very much Tom the iconic hobo poet. The club in the basement beneath is called ‘Underground’ (a song from Swordfishtrombones) and, of course it is a lovely pun – Tom(sk) Waits – geddit. It seems unlikely that Tom Waits’ management is aware of this brazen Siberian deployment but equally doubtful that Californian copyright law stretches quite this far. Waits is well known as an enthusiastic litigator of those who besmirch his image but this one seems to fit the brand perfectly.

Drop down a street or two to the west, away from the clubs and cafes of Prospekt Lenin, and you immediately find yourself in Old Siberia. A leafy street called Tatarskaya (this was once the city’s Tatar quarter) has old wooden houses with elaborately carved window surrounds and friezes. Poor, a little tumbledown but undeniably picturesque, this is the sort of thing that tourists come to see, although most tend not to wander this far off the direct Trans-Siberian route between Yekaterinberg and Irkutsk.

Drop down a street or two to the west, away from the clubs and cafes of Prospekt Lenin, and you immediately find yourself in Old Siberia. A leafy street called Tatarskaya (this was once the city’s Tatar quarter) has old wooden houses with elaborately carved window surrounds and friezes. Poor, a little tumbledown but undeniably picturesque, this is the sort of thing that tourists come to see, although most tend not to wander this far off the direct Trans-Siberian route between Yekaterinberg and Irkutsk.

Heading further north along Prospekt Lenin you soon reach a part of town that seems to have far more resonance with the old Soviet Union. Naturally enough, there is a Lenin statue here – this one in ‘hailing a taxi’ pose – as well as some brutalist Stalin-era civic buildings, Krushchevski apartment blocks and rusting boats at the river quay. This really could be a scene from almost anywhere in the former USSR pre-1991 but it is not – it is simply a matter of post-Soviet redevelopment not quite reaching this far uptown yet.

Heading further north along Prospekt Lenin you soon reach a part of town that seems to have far more resonance with the old Soviet Union. Naturally enough, there is a Lenin statue here – this one in ‘hailing a taxi’ pose – as well as some brutalist Stalin-era civic buildings, Krushchevski apartment blocks and rusting boats at the river quay. This really could be a scene from almost anywhere in the former USSR pre-1991 but it is not – it is simply a matter of post-Soviet redevelopment not quite reaching this far uptown yet.

Tomsk may have once been lauded as the ‘Siberian Athens’ thanks to its univeristies and large number of students but Anton Chekhov did not like it one bit, although surely it must have been an improvement on the penal colony at Sakhalin Island that he had visited prior to passing through the town.

Tomsk may have once been lauded as the ‘Siberian Athens’ thanks to its univeristies and large number of students but Anton Chekhov did not like it one bit, although surely it must have been an improvement on the penal colony at Sakhalin Island that he had visited prior to passing through the town.

He wrote to his sister: ‘Tomsk is a very dull town. To judge from the drunkards whose acquaintance I have made, and from the intellectual people who have come to the hotel to pay their respects to me, the inhabitants are very dull, too.’

Quite understandably, Tomsk citizens have never quite forgiven this scathing dismissal of their city and in response have erected a mocking statue of Chekhov close to the university. Perhaps wounded by the accusation of dullness, the authorities seem keen these days to instil some European-style civic fun into the Tomsk city calendar. They have inaugurated a carnival, and the one I witnessed last year was the fifth according to the posters. Roads were closed and a stage set up in the main square where a variety of acts came on to dance and mime to Russian turbo-pop. There was even a group of African djembe drummers hired for the task who grinned amiably as they performed to a bemused crowd that did not really know quite what to do. Young families and groups of friends watched the action on the stage and took pictures of each other with their mobile phones before sloping off for an ice-cream. No doubt it will take a while for imported carnival culture to catch on here – just two decades ago, rather than drumming Africans or disco-dancing teenagers, the citizens of Tomsk were watching processions of tanks and soldiers with supersized hats march by.

Quite understandably, Tomsk citizens have never quite forgiven this scathing dismissal of their city and in response have erected a mocking statue of Chekhov close to the university. Perhaps wounded by the accusation of dullness, the authorities seem keen these days to instil some European-style civic fun into the Tomsk city calendar. They have inaugurated a carnival, and the one I witnessed last year was the fifth according to the posters. Roads were closed and a stage set up in the main square where a variety of acts came on to dance and mime to Russian turbo-pop. There was even a group of African djembe drummers hired for the task who grinned amiably as they performed to a bemused crowd that did not really know quite what to do. Young families and groups of friends watched the action on the stage and took pictures of each other with their mobile phones before sloping off for an ice-cream. No doubt it will take a while for imported carnival culture to catch on here – just two decades ago, rather than drumming Africans or disco-dancing teenagers, the citizens of Tomsk were watching processions of tanks and soldiers with supersized hats march by.

While Tomsk may struggle with the concept of carnival it is doing well in the world of football. In recent years the city’s home side FC Tom Tomsk (their logo in Cyrillic spells TOMb) has risen like an eagle up the divisions to reach the dizzy heights of the Russian Premier League. It remains there, respectably mid-table, to this day. The Hotel Sputnik where I stayed is located right next door to the team’s stadium but sadly I had to move on to Irkutsk the day before their fixture with Lokomotiv Moscow.

While Tomsk may struggle with the concept of carnival it is doing well in the world of football. In recent years the city’s home side FC Tom Tomsk (their logo in Cyrillic spells TOMb) has risen like an eagle up the divisions to reach the dizzy heights of the Russian Premier League. It remains there, respectably mid-table, to this day. The Hotel Sputnik where I stayed is located right next door to the team’s stadium but sadly I had to move on to Irkutsk the day before their fixture with Lokomotiv Moscow.

For a look at another quirky Russian city, Kazan, take a look at my feature in the latest edition of hidden europe magazine here.

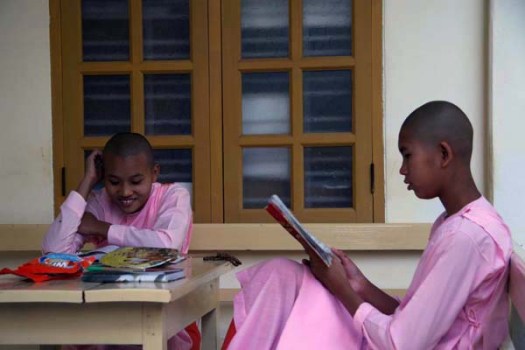

Buddhist nuns in Myanmar always dress in a fetching pink colour. A nun’s life is tough but they seem cheerful enough, collecting alms in the market, studying Pali sutras or sorting out clothes at the nunnery. The commitment is actually finite, as most Burmese girls only join the nunnery for a period of a few weeks at a time.

Buddhist nuns in Myanmar always dress in a fetching pink colour. A nun’s life is tough but they seem cheerful enough, collecting alms in the market, studying Pali sutras or sorting out clothes at the nunnery. The commitment is actually finite, as most Burmese girls only join the nunnery for a period of a few weeks at a time.

Young novice processing to Buddhist monastery near Hpa-an, Myanmar

Young novice processing to Buddhist monastery near Hpa-an, Myanmar

As

As

No-one came to sit next to me at Leavenworth but at Wenatchee an hour or so later I was joined by an elderly man called Dale who had just come from a week-long Lutheran Church retreat in the wilds of Washington State. “I see we’ve got us a groaner here”, were his first words to me as he wearily slumped down alongside, throwing a casual nod at the source of the shrill metallic wail that was emanating from the carriage wheels beneath us and had been doing so intermittently since leaving Seattle several hours earlier. Lean and bearded with plaid shirt and baseball cap, Dale might have looked like a typical retired Mid West farmer but was, in fact, a lay preacher in the no-nonsense undemonstrative Lutheran tradition. Despite an outward appearance that might give the impression of being a little ‘ornery’ Dale was the gentlest of men, with a playful, twinkly charm and a thoughtful, considered take on the world. We got talking about Alaska. He had spent a year there as a preacher on an isolated island close to the Arctic Circle just 40 miles from Russia (“And I mean 40 miles, not like that fool idea that that Sarah Palin woman had that she could see Russia from her house in Wasilla”). Dale’s northern sojourn had given him the greatest respect for the native people that endured the difficult living conditions of Alaska’s far north although he acknowledged that there were serious problems of alcohol abuse. “It was supposed to be a dry island but people being people they snuck it in somehow.”

No-one came to sit next to me at Leavenworth but at Wenatchee an hour or so later I was joined by an elderly man called Dale who had just come from a week-long Lutheran Church retreat in the wilds of Washington State. “I see we’ve got us a groaner here”, were his first words to me as he wearily slumped down alongside, throwing a casual nod at the source of the shrill metallic wail that was emanating from the carriage wheels beneath us and had been doing so intermittently since leaving Seattle several hours earlier. Lean and bearded with plaid shirt and baseball cap, Dale might have looked like a typical retired Mid West farmer but was, in fact, a lay preacher in the no-nonsense undemonstrative Lutheran tradition. Despite an outward appearance that might give the impression of being a little ‘ornery’ Dale was the gentlest of men, with a playful, twinkly charm and a thoughtful, considered take on the world. We got talking about Alaska. He had spent a year there as a preacher on an isolated island close to the Arctic Circle just 40 miles from Russia (“And I mean 40 miles, not like that fool idea that that Sarah Palin woman had that she could see Russia from her house in Wasilla”). Dale’s northern sojourn had given him the greatest respect for the native people that endured the difficult living conditions of Alaska’s far north although he acknowledged that there were serious problems of alcohol abuse. “It was supposed to be a dry island but people being people they snuck it in somehow.”