“a place appointed for worship in the time of heathenism”

Martin Martin A Description of the Western Islands of Scotland circa 1695

Someone once said that the wonder evoked by historical sites is inversely proportional to the number of eyes that have already gazed upon them. ‘Must-see’ tourism and mystery tend to stand in direct opposition. This is partly connected with the familiarity of the site itself — how well we think we already know somewhere from postcards, tourist board propaganda, travel features and social media. The Pyramids at Giza, probably the oldest tourist destination in the world, are a prime example. Magnificent though they may be, there is much at the site to detract from unbiased appreciation: crowds, trinket hawkers, faux guides, camel-hire men, and the very fact that an image of them has been burned into the retina since childhood even if we have never even stepped from these shores.

Similarly Stonehenge, England’s prime sacred site, which is of even greater antiquity and in many ways even more mysterious than the Egyptian pyramids in terms of function. In recent years, for perfectly understandable reasons, the monument has been sanitised and practically cling-film-wrapped by its guardians at English Heritage. New Age travellers, modern-day druids and miscellaneous stone-huggers are kept well away if at all possible, while the sightseeing general public is discouraged by means of fences, timed tickets, high entrance fees and the benign tear gas of lavender-wafted gift shops. The presence of large coach parties and the constantly rumbling A303 does little to engender a mystical atmosphere either. This may seem a little harsh but, personally speaking, I can no longer bring Stonehenge to mind without thinking of the film Spinal Tap and a particularly comical stage set.

‘Stonehenge! Where a man’s a man

And the children dance to the Pipes of Pan.’

A place which, for me, has far more resonance is Callanish on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. Not that it is undiscovered, far from it — this 5,000 year-old stone circle has long served as a poster girl for Scottish Highlands and Islands tourism promotions — but Callanish/Calanais is at least suitably remote, close to the western shore of Lewis and the best part of an hour’s drive from Stornoway, the main town on the island.

The first thing you notice on arrival — the stones themselves are already half-familiar thanks to photographic reproduction — is the immense beauty of the landscape that surrounds the site. Less raw and perhaps a little softer than some Lewis scenery, the stones stand on a bluff above the small eponymous village that developed in their shadow. The view from the hill is a pleasing vista of lochs and inlets, with the low hills of Great Bernera rising in the distance, the outlying stones of Calanais II and III pinpointed by distant figures on their way to view them.

The stones, of course, are not deserted of people — it is a fine late September day when we visit and visitors are making the most of the clement weather. A couple of tour minibuses are parked up outside the visitor centre and the gift shop and café are both enjoying a brisk trade. Walking the short track that leads to the stones we come upon a French tour group who are engaged in photographing each other as they stroll around the monoliths. Most of the women of the group sport black midge masks that droop in front of their faces like saggy proboscises — the fine mesh protecting them from ravaging insects. The donning of masks also appears to be an unconscious act of sympathetic magic as their chosen headgear makes them look uncannily like giant flies — biped flies, that is, garbed in Gore-Tex and Barbour. Truth be told, the midges are really not all that problematic and it seems that the French fly-women are perhaps overreacting to the perceived threat. It seems a little ironic, too, that they hail from a country that banned all-enveloping face coverings like the burqa just a few years ago.

The site is relatively busy yet the proverbial camera proves to be an efficient liar. It is approaching lunchtime; the crowd around the stones has already thinned, and it does not take long to snap a number of images in which no human presence is detectable. No doubt, with sufficient Photoshop tweaking, I could possibly also adjust the contrast and saturation to simulate a sunrise rather than late morning scene. But I am happy as things are and reflect that as most of the evidence points towards Callanish being constructed as a temple orientated to moon-rise I really ought to be here at night instead.

The Callanish site is well known and rightly cherished but there are other, less-heralded standing stones in the vicinity. The previous day we had come across a small group of monoliths close to the bridge that leads across to Great Bernera. These stones, fewer but similar in size and shape to those at Callanish, were of the same three-billion-year-old Lewisian gneiss, one of the oldest rocks on Earth. Known locally as Tursachan (Gaelic for ‘standing stones’), or more prosaically by archaeologists as Callanish VIII, they stood on the island of Great Bernera overlooking the bridge from the Lewis mainland. Formerly an island off an island (Lewis and Harris), which, in turn, stands off a much larger island (Scotland, England and Wales), Great Bernera has only been connected to Lewis by bridge since 1953. When first erected, the semi-circle of four large stones would have stood sentinel-like overlooking the straight between the island and Lewis; now they overlook the bridge that connects them. Unlike their better known neighbours to the east these stones are now almost forgotten. With little more than a modest signpost to point them out, they are a sidebar of prehistory, mere cartographic marginalia on the OS Explorer 458 West Lewis map.

Eleven miles east of the main road, six from the nearest shop (closed on the Sabbath), two miles from the open sea as the raven flies. Glen Gravir – a slender thread of houses stretching up a glen, just four more unoccupied dwellings beyond ours before the road abruptly terminates at a fence, nothing but rough wet grazing, soggy peat and unseen lochans beyond. This was our home for the week, a holiday rental in the Park (South Lochs) district of the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides.

Eleven miles east of the main road, six from the nearest shop (closed on the Sabbath), two miles from the open sea as the raven flies. Glen Gravir – a slender thread of houses stretching up a glen, just four more unoccupied dwellings beyond ours before the road abruptly terminates at a fence, nothing but rough wet grazing, soggy peat and unseen lochans beyond. This was our home for the week, a holiday rental in the Park (South Lochs) district of the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. Gravir, of which Glen Gravir is but an outpost, is large enough to feature on the map, albeit in its Gaelic form, Grabhair. The village – more a loose straggle of houses and plots – possesses a school, a fire station and a church but no shop. A road from the junction with Glenside next to the church winds its way unhurriedly downhill to the sea inlet of Loch Odhairn where there is a small jetty for boats. Some of the houses are clearly empty; others occupied by crofters and incomers, their occupants largely unseen. Others are long ruined, tenanted only by raven and opportunist rowan trees, with roofs absent and little more than chimney stacks and gable walls surviving. It is only a matter of time before the stones that have been laid to construct the walls will be indistinguishable from the native gneiss that underlies the island, surfacing above the bog here and there in outcrops like human-raised cairns. Lewisian gneiss is the oldest rock in Britain. Three billion years old, two-thirds the age of our planet, it is as hard as…well, gneiss. It is the same tough unyielding rock that five thousand years ago was painstakingly worked and positioned at the Callanish stone circle close to Lewis’s western shore; the same rock used to build the island’s churches, which occupy the same sacred sites, the same fixed points of genii loci that had been identified long before Presbyterianism or any another monotheistic faith arrived in these isolated north-western isles.

Gravir, of which Glen Gravir is but an outpost, is large enough to feature on the map, albeit in its Gaelic form, Grabhair. The village – more a loose straggle of houses and plots – possesses a school, a fire station and a church but no shop. A road from the junction with Glenside next to the church winds its way unhurriedly downhill to the sea inlet of Loch Odhairn where there is a small jetty for boats. Some of the houses are clearly empty; others occupied by crofters and incomers, their occupants largely unseen. Others are long ruined, tenanted only by raven and opportunist rowan trees, with roofs absent and little more than chimney stacks and gable walls surviving. It is only a matter of time before the stones that have been laid to construct the walls will be indistinguishable from the native gneiss that underlies the island, surfacing above the bog here and there in outcrops like human-raised cairns. Lewisian gneiss is the oldest rock in Britain. Three billion years old, two-thirds the age of our planet, it is as hard as…well, gneiss. It is the same tough unyielding rock that five thousand years ago was painstakingly worked and positioned at the Callanish stone circle close to Lewis’s western shore; the same rock used to build the island’s churches, which occupy the same sacred sites, the same fixed points of genii loci that had been identified long before Presbyterianism or any another monotheistic faith arrived in these isolated north-western isles. Ancient hard rock (as in metamorphic) may underlie Lewis, but religion is another bedrock of the island. Despite a respectable number of dwellings the only people we ever really see in the village are those who come in number on Sunday. The Hebridean Wee Free tradition guarantees a full car park on the Sabbath when smartly and soberly dressed folk from the wider locality congregate at Grabhair’s church, which, grave, grey and impressively large, is the only place of worship in this eastern part of the South Lochs district.

Ancient hard rock (as in metamorphic) may underlie Lewis, but religion is another bedrock of the island. Despite a respectable number of dwellings the only people we ever really see in the village are those who come in number on Sunday. The Hebridean Wee Free tradition guarantees a full car park on the Sabbath when smartly and soberly dressed folk from the wider locality congregate at Grabhair’s church, which, grave, grey and impressively large, is the only place of worship in this eastern part of the South Lochs district.

At the bottom of the lane beneath the hillside graveyard next to the church are a couple of recycling containers for villagers to deposit their empties and waste paper. Larger items of material consumption are left to their own devices. Rain, wind and thin acidic soil are the natural agents of decay here. Beside the roadside further up from our house lie four long-abandoned vehicles in various stages of decomposition. Engines are laid bare; bodywork and chassis, buckled and distressed, rust-coated in mimicry of the colour of lichen and autumn-faded heather. Cushions of moss have colonised the seating fabric. The rubber tyres remain surprisingly intact, the longest survivor of abandonment. Sharp-edged sedges have grown around the rotting car-carcasses as if to hide them from prying eyes, preserving some modicum of dignity as the wrecks decay into the roadside bog, all glamour expunged from a lifetime spent negotiating the island’s narrow single track roads. On Lewis, vehicles die of natural causes, not geriatric intervention.

At the bottom of the lane beneath the hillside graveyard next to the church are a couple of recycling containers for villagers to deposit their empties and waste paper. Larger items of material consumption are left to their own devices. Rain, wind and thin acidic soil are the natural agents of decay here. Beside the roadside further up from our house lie four long-abandoned vehicles in various stages of decomposition. Engines are laid bare; bodywork and chassis, buckled and distressed, rust-coated in mimicry of the colour of lichen and autumn-faded heather. Cushions of moss have colonised the seating fabric. The rubber tyres remain surprisingly intact, the longest survivor of abandonment. Sharp-edged sedges have grown around the rotting car-carcasses as if to hide them from prying eyes, preserving some modicum of dignity as the wrecks decay into the roadside bog, all glamour expunged from a lifetime spent negotiating the island’s narrow single track roads. On Lewis, vehicles die of natural causes, not geriatric intervention.

Our cottage was rented as an island base: a place to eat, rest and sleep before setting off each morning on a long drive to visit one of Lewis’s far flung corners. Happily, it feels like a home, albeit a temporary one – a domestic cocoon of cosiness with all the modest comforts we require. Its small garden is a haven. As everywhere on the island, tangerine spikes of montbretia arch like welder’s sparks from the grass. Rabbits scamper about on the lawn, colour-flushed parties of goldfinches feed on the seed heads of knapweed outside the kitchen window. Robins, wrens and blackbirds flit around the trees and shrubs that envelop the cottage – non-native plants that have adapted to the harsh weather conditions of this north-western island, softening an outlook that on a grey, wind-blown day, with a gloomy frame of mind, might be considered bleak.

Our cottage was rented as an island base: a place to eat, rest and sleep before setting off each morning on a long drive to visit one of Lewis’s far flung corners. Happily, it feels like a home, albeit a temporary one – a domestic cocoon of cosiness with all the modest comforts we require. Its small garden is a haven. As everywhere on the island, tangerine spikes of montbretia arch like welder’s sparks from the grass. Rabbits scamper about on the lawn, colour-flushed parties of goldfinches feed on the seed heads of knapweed outside the kitchen window. Robins, wrens and blackbirds flit around the trees and shrubs that envelop the cottage – non-native plants that have adapted to the harsh weather conditions of this north-western island, softening an outlook that on a grey, wind-blown day, with a gloomy frame of mind, might be considered bleak. Most days on our jaunts around the island we would see an eagle or two, golden or white-tailed, sometimes both. The majority of these sighting are in more mountainous Harris, or in that southern part of Lewis that lay close to the North Harris Hills, but on our last day on Lewis we see a white-tailed eagle fly over Orinsay, a village relatively close to where we have been staying. An hour later we spot another bird swoop along the sea loch at Cromore, a coastal village that lies a few miles to the north. It might well be the same bird. White-tailed eagles are very large and hard to miss, and their feeding range is enormous. But that is exactly how Lewis seems – enormous, almost unknowable despite its modest geographical area. A place larger than the shape on the map – a mutable landscape of rock, sky and water that does not easily lend itself to the reductionism of two-dimensional cartography.

Most days on our jaunts around the island we would see an eagle or two, golden or white-tailed, sometimes both. The majority of these sighting are in more mountainous Harris, or in that southern part of Lewis that lay close to the North Harris Hills, but on our last day on Lewis we see a white-tailed eagle fly over Orinsay, a village relatively close to where we have been staying. An hour later we spot another bird swoop along the sea loch at Cromore, a coastal village that lies a few miles to the north. It might well be the same bird. White-tailed eagles are very large and hard to miss, and their feeding range is enormous. But that is exactly how Lewis seems – enormous, almost unknowable despite its modest geographical area. A place larger than the shape on the map – a mutable landscape of rock, sky and water that does not easily lend itself to the reductionism of two-dimensional cartography.

The Japanese have an expression – shirin-yoku (‘forest bathing’) — which refers to time spent in a wood or forest for purposes of health and relaxation. Scientific field studies have demonstrated that spending even a short time among trees promotes a lower concentration of cortisones, lower pulse, lower blood pressure, decreased levels of stress and improved concentration. In Japan activities such as shirin-yoku are part of the culture and hold an important place in the national psyche. Modern Japanese culture is still rooted in ancient nature-worshipping Shinto beliefs that are expressed in a variety of ways. Perhaps the most striking of these for westerners is the annual celebration of the

The Japanese have an expression – shirin-yoku (‘forest bathing’) — which refers to time spent in a wood or forest for purposes of health and relaxation. Scientific field studies have demonstrated that spending even a short time among trees promotes a lower concentration of cortisones, lower pulse, lower blood pressure, decreased levels of stress and improved concentration. In Japan activities such as shirin-yoku are part of the culture and hold an important place in the national psyche. Modern Japanese culture is still rooted in ancient nature-worshipping Shinto beliefs that are expressed in a variety of ways. Perhaps the most striking of these for westerners is the annual celebration of the  The forest, the greenwood, comes with cultural baggage. It is sensed to be a place of ‘the Other’, a place of wild things, of decay, of hidden danger; of runaway fugitives, mythical outlaws — Robin Hood being prime example — deserted children (Babes in the Wood), ghosts and malevolent spirits. There is no denying that some tracts of woodland are downright spooky, places where dark forces can be felt to be at large. Traditional children’s literature does not help much in mitigating this irrational if primal fear. In fact, it nourishes it — one of the very first books I remember reading as a small child was Winkie Lost in the Deep, Deep Woods, the very title of which suggests some sort of unspoken dark menace. As an archetype, a forest is perceived as an eldritch zone where wicked witches live alone in eerie hovels, where red-cloaked little girls are preyed upon by egregious wolves, and large gatherings of ursine cuddly toys attend sinister secret picnics. Go into the woods (today) and you might well be ‘sure of a big surprise’. In adult life the same fear is perpetuated as a trope of the horror genre — the psychological terror of The Blair Witch Project springs to mind. The forest is a place where bad things happen — a place to bury the bodies. Be afraid. Even Japan with its devotion to sakura and forest bathing traditions has its fair share of indigenous forest demons. The country even has its own haunted forest, Aokigahara, at the foot of Mount Fuji, which has the unenviable reputation of beings the world’s second most popular choice as a place for suicide.

The forest, the greenwood, comes with cultural baggage. It is sensed to be a place of ‘the Other’, a place of wild things, of decay, of hidden danger; of runaway fugitives, mythical outlaws — Robin Hood being prime example — deserted children (Babes in the Wood), ghosts and malevolent spirits. There is no denying that some tracts of woodland are downright spooky, places where dark forces can be felt to be at large. Traditional children’s literature does not help much in mitigating this irrational if primal fear. In fact, it nourishes it — one of the very first books I remember reading as a small child was Winkie Lost in the Deep, Deep Woods, the very title of which suggests some sort of unspoken dark menace. As an archetype, a forest is perceived as an eldritch zone where wicked witches live alone in eerie hovels, where red-cloaked little girls are preyed upon by egregious wolves, and large gatherings of ursine cuddly toys attend sinister secret picnics. Go into the woods (today) and you might well be ‘sure of a big surprise’. In adult life the same fear is perpetuated as a trope of the horror genre — the psychological terror of The Blair Witch Project springs to mind. The forest is a place where bad things happen — a place to bury the bodies. Be afraid. Even Japan with its devotion to sakura and forest bathing traditions has its fair share of indigenous forest demons. The country even has its own haunted forest, Aokigahara, at the foot of Mount Fuji, which has the unenviable reputation of beings the world’s second most popular choice as a place for suicide.  But let us embrace a positive outlook and view woodland as a place of wonder and nurture rather than fear and loathing, a place to breathe in the beneficial volatile oils emitted by trees and enjoy their beauty. Where better to delve into the greenwood in Britain than a tract of temperate rainforest that has hardly changed since the last glacial period? Coed Felinrhyd in North Wales has stood largely untouched since from this period and, although tracts of this woodland have been partially managed over the centuries, other parts have remained undisturbed for around 10,000 years. Coed Felinrhyd, owned by the Woodland Trust, is just a fraction of the remnant temperate rainforest found in this damp corner of Wales: a 90-hectare tract of woodland on the southern side of the narrow Ceunant Llennyrch gorge through which the mercurial Afon Pryser, a tributary of the Afon Dwyryd, flows. Coed Felinrhyd’s particularities of relief and climate, tucked away in a sheltered, virtually frost-free gorge close to the Welsh coast in a region where it rains on average 200 days a year, ensure that the ecosystem here is in many ways unique. Scarce plants and ferns thrive in the understory, rare lichens and mosses cloak the trees. But this is more than simply remarkable ecosysytem, this is also a place where geography and legend intertwine – the forest receives a mention in the ancient Mabinogion myths written down in the 12th century and is said to be the location where two warriors once fought to the death.

But let us embrace a positive outlook and view woodland as a place of wonder and nurture rather than fear and loathing, a place to breathe in the beneficial volatile oils emitted by trees and enjoy their beauty. Where better to delve into the greenwood in Britain than a tract of temperate rainforest that has hardly changed since the last glacial period? Coed Felinrhyd in North Wales has stood largely untouched since from this period and, although tracts of this woodland have been partially managed over the centuries, other parts have remained undisturbed for around 10,000 years. Coed Felinrhyd, owned by the Woodland Trust, is just a fraction of the remnant temperate rainforest found in this damp corner of Wales: a 90-hectare tract of woodland on the southern side of the narrow Ceunant Llennyrch gorge through which the mercurial Afon Pryser, a tributary of the Afon Dwyryd, flows. Coed Felinrhyd’s particularities of relief and climate, tucked away in a sheltered, virtually frost-free gorge close to the Welsh coast in a region where it rains on average 200 days a year, ensure that the ecosystem here is in many ways unique. Scarce plants and ferns thrive in the understory, rare lichens and mosses cloak the trees. But this is more than simply remarkable ecosysytem, this is also a place where geography and legend intertwine – the forest receives a mention in the ancient Mabinogion myths written down in the 12th century and is said to be the location where two warriors once fought to the death.  The entrance is a little hard to find, hidden away just beyond the entrance to the Maentwrog power station on the Blenau Ffestiniog to Harlech road. A Woodland Trust notice board by the gate gives background information on Coed Felinrhyd and a signpost points out the direction of a well-defined trail that circuits the forest. The trail climbs steeply at first, then more gently before levelling off. The first thing to be noticed, other than the towering oaks that stretch in every direction, is moss. Although ferns are almost as prolific, sprouting like green shuttlecocks wherever they can secure a foothold, it is moss that is everywhere cloaking every surface — on the bark of trees, on the rocks that line the pathway, on the dry stone walls that partition the woodland; on any surface where moisture can collect. Even most of the tree stumps are upholstered with velvety jade cushions of moss, their cut surface having been rapidly colonised by the feathery fronds of bryophytes. Each of these is a pedestal-raised forest in miniature, a Lilliputian lost world — this small tract of woodland contains a million tiny moss forests within it. Some of the tree stumps have been cut mischievously into the shape of a chair or a four-legged stool, the work of a rogue woodsman with a sense of humour and an artistic streak. A few of are fresh enough to not yet sport the forest’s inevitable green uniform, although no doubt soon they will.

The entrance is a little hard to find, hidden away just beyond the entrance to the Maentwrog power station on the Blenau Ffestiniog to Harlech road. A Woodland Trust notice board by the gate gives background information on Coed Felinrhyd and a signpost points out the direction of a well-defined trail that circuits the forest. The trail climbs steeply at first, then more gently before levelling off. The first thing to be noticed, other than the towering oaks that stretch in every direction, is moss. Although ferns are almost as prolific, sprouting like green shuttlecocks wherever they can secure a foothold, it is moss that is everywhere cloaking every surface — on the bark of trees, on the rocks that line the pathway, on the dry stone walls that partition the woodland; on any surface where moisture can collect. Even most of the tree stumps are upholstered with velvety jade cushions of moss, their cut surface having been rapidly colonised by the feathery fronds of bryophytes. Each of these is a pedestal-raised forest in miniature, a Lilliputian lost world — this small tract of woodland contains a million tiny moss forests within it. Some of the tree stumps have been cut mischievously into the shape of a chair or a four-legged stool, the work of a rogue woodsman with a sense of humour and an artistic streak. A few of are fresh enough to not yet sport the forest’s inevitable green uniform, although no doubt soon they will.  Having reached a plateau in the woods we come across a ruined slate barn beside the trail, its roof long gone and ferns sprouting like bunting on top of the walls where the eaves should be. Long abandoned, the building is probably at least two hundred years old and a remnant of the old farming practice of ‘hafod a hendre’ in which shepherds would remain on higher pasture with their flocks during summer. The track continues past clumps of trees that seem to emerge directly from the moss-carpeted boulders at their base. The blanket of moss and lichens that covers both gives the impression that both tree and rock are born of the same material, something primal and green that is neither strictly vegetable or mineral but something in between.

Having reached a plateau in the woods we come across a ruined slate barn beside the trail, its roof long gone and ferns sprouting like bunting on top of the walls where the eaves should be. Long abandoned, the building is probably at least two hundred years old and a remnant of the old farming practice of ‘hafod a hendre’ in which shepherds would remain on higher pasture with their flocks during summer. The track continues past clumps of trees that seem to emerge directly from the moss-carpeted boulders at their base. The blanket of moss and lichens that covers both gives the impression that both tree and rock are born of the same material, something primal and green that is neither strictly vegetable or mineral but something in between. Descending back down into the valley we arrive at a dry stone wall that has a gate which leads into Llennyrch, a neighbouring tract of forest of similar pedigree to Coed Felinrhyd. We follow the wall to the left and the sound of rushing water becomes gradually louder as the gorge reveals itself. A small viewing platform gives a glimpse of the waterfall of Rhaeadr Ddu that plummets down onto the rocks below although the view is partly obscured by the dense foliage. The river is still some way beneath us but we draw closer to it as the path gradually descends. Finally we come to Ivy Bridge, which, true to name, is enveloped by long trails of ivy that hang over the edge almost touching the water and rocks beneath. Beyond the bridge, on the other side of the river, the unsightly machinery of an electricity substation can be discerned beyond a fence; beyond this, unseen from this position, lies the Maentwrog power station.

Descending back down into the valley we arrive at a dry stone wall that has a gate which leads into Llennyrch, a neighbouring tract of forest of similar pedigree to Coed Felinrhyd. We follow the wall to the left and the sound of rushing water becomes gradually louder as the gorge reveals itself. A small viewing platform gives a glimpse of the waterfall of Rhaeadr Ddu that plummets down onto the rocks below although the view is partly obscured by the dense foliage. The river is still some way beneath us but we draw closer to it as the path gradually descends. Finally we come to Ivy Bridge, which, true to name, is enveloped by long trails of ivy that hang over the edge almost touching the water and rocks beneath. Beyond the bridge, on the other side of the river, the unsightly machinery of an electricity substation can be discerned beyond a fence; beyond this, unseen from this position, lies the Maentwrog power station. After two hours of slow walking, looking, taking photographs and what can only be described as mobile ‘forest bathing’ we are back where we started. It suddenly occurs that we have met absolutely no one on our walk even though it is a relatively bright day with little threat of rain. No hikers or dog walkers, no botanists or tree-huggers, no Celtic warrior ghosts. And, to the best of our knowledge, no malevolent woodland sprites either.

After two hours of slow walking, looking, taking photographs and what can only be described as mobile ‘forest bathing’ we are back where we started. It suddenly occurs that we have met absolutely no one on our walk even though it is a relatively bright day with little threat of rain. No hikers or dog walkers, no botanists or tree-huggers, no Celtic warrior ghosts. And, to the best of our knowledge, no malevolent woodland sprites either.

The Saints is a small, loosely defined area of northeast Suffolk just south of the River Waveney and the Norfolk border. Effectively it is a fairly unremarkable patch of arable countryside that contains within it a baker’s dozen of small villages with names that begin or end with the name of the parish saint: St Peter South Elmham, St Michael South Elmham, St Nicholas South Elmham, St James South Elmham, St Margaret South Elmham, St Mary South Elmham, St Cross South Elmham, All Saints South Elmham, Ilketshall St Andrew, Ilketshall St Lawrence, Ilketshall St Margaret, Ilketshall St John and All Saints Mettingham. The area is bisected in its eastern fringe by the Bungay—Halesworth road that follows the course of Stone Street, a die-straight Roman construction, one of several that can still be traced on any road map of East Anglia. On the whole though the roads around here are anything but Roman in character: narrow, twisting, often bewilderingly changing direction, and marked with confusing signs (too many saints!), it is a good place to visit should you wish to humiliate your Sat Nav. John Seymour in The Companion Guide to East Anglia (1968) describes The Saints as ‘a hillbilly land into which nobody penetrates unless he has good business,’ which is perhaps hyperbolic but there is undoubtedly a feel of liminality to the area that persists to this day.

The Saints is a small, loosely defined area of northeast Suffolk just south of the River Waveney and the Norfolk border. Effectively it is a fairly unremarkable patch of arable countryside that contains within it a baker’s dozen of small villages with names that begin or end with the name of the parish saint: St Peter South Elmham, St Michael South Elmham, St Nicholas South Elmham, St James South Elmham, St Margaret South Elmham, St Mary South Elmham, St Cross South Elmham, All Saints South Elmham, Ilketshall St Andrew, Ilketshall St Lawrence, Ilketshall St Margaret, Ilketshall St John and All Saints Mettingham. The area is bisected in its eastern fringe by the Bungay—Halesworth road that follows the course of Stone Street, a die-straight Roman construction, one of several that can still be traced on any road map of East Anglia. On the whole though the roads around here are anything but Roman in character: narrow, twisting, often bewilderingly changing direction, and marked with confusing signs (too many saints!), it is a good place to visit should you wish to humiliate your Sat Nav. John Seymour in The Companion Guide to East Anglia (1968) describes The Saints as ‘a hillbilly land into which nobody penetrates unless he has good business,’ which is perhaps hyperbolic but there is undoubtedly a feel of liminality to the area that persists to this day.  The village names conjure a medieval world where saint-obsessed religion loomed large. Such a tight cluster of settlements suggests a concentration of population where parishes might eventually combine to form a town or city – with 13 villages and the same number of churches (eleven of which are extant), there were more churches here than in all of Cambridge. But The Saints never coalesced to become a medieval city – none of the villages had a port, defensive structure or even significant market to its credit and consequently the area would slowly slip into obscurity as the medieval era played out and other East Anglia towns and cities – Cambridge, Bury St Edmunds, Ipswich and, of course, Norwich – took the baton of influence and power.

The village names conjure a medieval world where saint-obsessed religion loomed large. Such a tight cluster of settlements suggests a concentration of population where parishes might eventually combine to form a town or city – with 13 villages and the same number of churches (eleven of which are extant), there were more churches here than in all of Cambridge. But The Saints never coalesced to become a medieval city – none of the villages had a port, defensive structure or even significant market to its credit and consequently the area would slowly slip into obscurity as the medieval era played out and other East Anglia towns and cities – Cambridge, Bury St Edmunds, Ipswich and, of course, Norwich – took the baton of influence and power.  It was not always so: one of the villages in particular held great significance in its day. The land covered by the South Elmham parishes was once owned by Almar, Bishop of East Anglia and the late Saxon Bishops of Norwich had a summer palace here at St Cross, now South Elmham Hall. The most intriguing of the churches lies within the same parish. It is not in any way complete but a ruin framed by woodland a good half mile from the nearest road. South Elmham Minster, although probably never a minster proper, is veiled in mystery regarding its origins but its appeal owes as much to its half-hidden location as it does to its obscure history. South Elmham may have once been the seat of the second East Anglian bishopric (the first was in Dunwich, the sea-ravaged village on the Suffolk coast), although North Elmham in Norfolk seems a more likely contender. Whatever the ruin’s original function – a private chapel for Herbert de Losinga, Norwich’s first bishop, is another possibility, or it may even be that a second bishopric was founded here – the church in the wood just south of South Elmham Hall dates back at least to the 11th century. It is probably older in origin – a ninth-century gravestone has been unearthed in its foundations. The site itself is undoubtedly of greater antiquity: a continuation of an earlier Anglo-Saxon presence that occupied the same moated site, which, earlier still, was home to a Roman temple and perhaps, even earlier, a pagan holy place.

It was not always so: one of the villages in particular held great significance in its day. The land covered by the South Elmham parishes was once owned by Almar, Bishop of East Anglia and the late Saxon Bishops of Norwich had a summer palace here at St Cross, now South Elmham Hall. The most intriguing of the churches lies within the same parish. It is not in any way complete but a ruin framed by woodland a good half mile from the nearest road. South Elmham Minster, although probably never a minster proper, is veiled in mystery regarding its origins but its appeal owes as much to its half-hidden location as it does to its obscure history. South Elmham may have once been the seat of the second East Anglian bishopric (the first was in Dunwich, the sea-ravaged village on the Suffolk coast), although North Elmham in Norfolk seems a more likely contender. Whatever the ruin’s original function – a private chapel for Herbert de Losinga, Norwich’s first bishop, is another possibility, or it may even be that a second bishopric was founded here – the church in the wood just south of South Elmham Hall dates back at least to the 11th century. It is probably older in origin – a ninth-century gravestone has been unearthed in its foundations. The site itself is undoubtedly of greater antiquity: a continuation of an earlier Anglo-Saxon presence that occupied the same moated site, which, earlier still, was home to a Roman temple and perhaps, even earlier, a pagan holy place.  We leave the car in a muddy parking area alongside another vehicle and a dumped piece of agricultural machinery. Nearby stands a weather-beaten trestle table that suggests that this once might have served as a designated picnic spot. Now half-submerged in grass and thistles, the table did not look as if any sandwich boxes had been opened on it for some time. Things have changed here a little in recent years: the permissive footpaths that once threaded through the South Elmham estate are no longer available for the public, and the hall itself has been re-purposed for use as a wedding and conference venue. At least the minster was still accessible by means of a green lane and a public footpath across fields.

We leave the car in a muddy parking area alongside another vehicle and a dumped piece of agricultural machinery. Nearby stands a weather-beaten trestle table that suggests that this once might have served as a designated picnic spot. Now half-submerged in grass and thistles, the table did not look as if any sandwich boxes had been opened on it for some time. Things have changed here a little in recent years: the permissive footpaths that once threaded through the South Elmham estate are no longer available for the public, and the hall itself has been re-purposed for use as a wedding and conference venue. At least the minster was still accessible by means of a green lane and a public footpath across fields.  The green lane is flanked by mature hedges frothed white with blackthorn blossom. Reaching its bottom end we turn left to follow a footpath alongside a stream, a minor tributary of the River Waveney; strange hollowed-out hornbeams measure out its bank. Soon we come to the copse that contains the ruin, a rusty gate gives admission across a partial moat and raised bank into what can only be described as a woodland glade. The ancient flint walls of the church stand central, striated by the shadow of hornbeams still leafless in late March. There is no sign of a roof but the weathered walls of the nave are clear in outline, as is the single entrance to the west. On the ground, last year’s fallen leaves provide a soft bronze carpet that is mostly devoid of ground plants.

The green lane is flanked by mature hedges frothed white with blackthorn blossom. Reaching its bottom end we turn left to follow a footpath alongside a stream, a minor tributary of the River Waveney; strange hollowed-out hornbeams measure out its bank. Soon we come to the copse that contains the ruin, a rusty gate gives admission across a partial moat and raised bank into what can only be described as a woodland glade. The ancient flint walls of the church stand central, striated by the shadow of hornbeams still leafless in late March. There is no sign of a roof but the weathered walls of the nave are clear in outline, as is the single entrance to the west. On the ground, last year’s fallen leaves provide a soft bronze carpet that is mostly devoid of ground plants.  Church or not, there is a timelessness to this place in the woods. And a strong sense of genius loci, the sort of thing that put the wind up the Romans with their straight lines and four-square militaristic outlook. I wander off to explore the bank to the west and discover the opening of a badger sett that looks to be newly excavated. Without much expectation, I rummage though the spoil musing that there might just be the remotest of chances that, burrowing deep beneath the mound, the animals have thrown up some treasure long buried in the soil below: an Anglo-Saxon torc, a Roman coin perhaps? I would even settle for a rusty button, but nothing. No matter, the mystery of the place is enough for now. We leave the bosky comfort of the site and retrace our steps along the beck and green lane back to the car. The other car has gone – we never did see its occupants.

Church or not, there is a timelessness to this place in the woods. And a strong sense of genius loci, the sort of thing that put the wind up the Romans with their straight lines and four-square militaristic outlook. I wander off to explore the bank to the west and discover the opening of a badger sett that looks to be newly excavated. Without much expectation, I rummage though the spoil musing that there might just be the remotest of chances that, burrowing deep beneath the mound, the animals have thrown up some treasure long buried in the soil below: an Anglo-Saxon torc, a Roman coin perhaps? I would even settle for a rusty button, but nothing. No matter, the mystery of the place is enough for now. We leave the bosky comfort of the site and retrace our steps along the beck and green lane back to the car. The other car has gone – we never did see its occupants.

Today is St Patrick’s Day and March 17 is the supposed date of the 5th-century missionary’s death. Patrick was the forerunner of many early missionaries who came to Irish shores to preach Christianity, the island more receptive to new ideas about religion than its larger neighbour to the east across the Irish Sea. Consequently Ireland abounds with relics and ruins of early Christianity, sometimes in the most improbable of places.

Today is St Patrick’s Day and March 17 is the supposed date of the 5th-century missionary’s death. Patrick was the forerunner of many early missionaries who came to Irish shores to preach Christianity, the island more receptive to new ideas about religion than its larger neighbour to the east across the Irish Sea. Consequently Ireland abounds with relics and ruins of early Christianity, sometimes in the most improbable of places. Sailing around Ireland’s southwest coast, skirting the peninsulas that splay out from the Kerry coast, the two islands of the Skelligs come into view after rounding Bolus Head at the end of the Inveragh Peninsula. Both islands are sheer, with sharp-finned summits that resemble inverted boat keels. The smaller of the two appears largely white at first but increasing proximity reveals that the albino effect is down to a combination of nesting gannets and guano. The acrid tang of ammonia on the breeze and distant cacophony announce the presence of the birds well before the identity of any individual can be confirmed by binoculars.

Sailing around Ireland’s southwest coast, skirting the peninsulas that splay out from the Kerry coast, the two islands of the Skelligs come into view after rounding Bolus Head at the end of the Inveragh Peninsula. Both islands are sheer, with sharp-finned summits that resemble inverted boat keels. The smaller of the two appears largely white at first but increasing proximity reveals that the albino effect is down to a combination of nesting gannets and guano. The acrid tang of ammonia on the breeze and distant cacophony announce the presence of the birds well before the identity of any individual can be confirmed by binoculars. As the boat draws closer, the sheer volume of birds – gannets, fulmars, puffins, terns – becomes plain to see. With something like 70,000 birds, Little Skellig is the second largest gannet colony in the world. But on the larger island of Skellig Michael, although seabirds abound here too, there is also the suggestion of a human presence, albeit an historic one. High up in the rocks, small stone structures can be discerned: rounded domes that are clearly man-made and which soften the jagged silhouette of the island’s summit. These are beehive cells, the dry-stone oratories favoured by early Irish monks for their meditation. Sitting aloft the island on a high terrace, commanding a panoramic view over the Atlantic Ocean in one direction and the fractal Kerry coast in the other, these simple stone cells came without windows – the business was one of prayer and meditation not horizon-gazing. Such isolation was necessary for reasons of both safety and spirituality. And Skellig Michael was the acme of isolation. In the early Christian milieu the Skellig Islands, facing the seemingly limitless Atlantic off the southwest coast of Ireland, were more than merely remote: they were at the very edge of the known world.

As the boat draws closer, the sheer volume of birds – gannets, fulmars, puffins, terns – becomes plain to see. With something like 70,000 birds, Little Skellig is the second largest gannet colony in the world. But on the larger island of Skellig Michael, although seabirds abound here too, there is also the suggestion of a human presence, albeit an historic one. High up in the rocks, small stone structures can be discerned: rounded domes that are clearly man-made and which soften the jagged silhouette of the island’s summit. These are beehive cells, the dry-stone oratories favoured by early Irish monks for their meditation. Sitting aloft the island on a high terrace, commanding a panoramic view over the Atlantic Ocean in one direction and the fractal Kerry coast in the other, these simple stone cells came without windows – the business was one of prayer and meditation not horizon-gazing. Such isolation was necessary for reasons of both safety and spirituality. And Skellig Michael was the acme of isolation. In the early Christian milieu the Skellig Islands, facing the seemingly limitless Atlantic off the southwest coast of Ireland, were more than merely remote: they were at the very edge of the known world. The island’s monastic site is infused with mystery, as all good ruins are, but is thought to have been established in the 6th century by Saint Fionán. Consisting of six beehive cells, two oratories and a later medieval church, the site occupies a stone terrace 600 feet above the swirling green waters of the sea below.

The island’s monastic site is infused with mystery, as all good ruins are, but is thought to have been established in the 6th century by Saint Fionán. Consisting of six beehive cells, two oratories and a later medieval church, the site occupies a stone terrace 600 feet above the swirling green waters of the sea below. Skirting Skellig Michael, a landing stage with a helicopter pad comes into view. A vertiginous path of stone steps leads up towards the beehive huts close to the island’s mountain-like summit. We do not disembark. Instead we keep sailing, bound for a safer harbour in Glengarriff in County Cork. No matter, the sight of the rocks, the winding, climbing path and the austere cells on the terrace at the top is already imprinted on our memory.

Skirting Skellig Michael, a landing stage with a helicopter pad comes into view. A vertiginous path of stone steps leads up towards the beehive huts close to the island’s mountain-like summit. We do not disembark. Instead we keep sailing, bound for a safer harbour in Glengarriff in County Cork. No matter, the sight of the rocks, the winding, climbing path and the austere cells on the terrace at the top is already imprinted on our memory. Without doubt this was a life of supreme hardship: the isolation, the relentless diet of fish and seabird eggs, the ever-battering wind and salt-spray. Such was the isolation, and so extreme the privations of this beatific pursuit, that one might assume that the monks would have been left in peace to practice their calling. This was not to be. Viking raiders arrived here in the early 9th century and took the trouble to land, scale the island’s heights and attack the monks. For most of us it is probably difficult to comprehend the blind-rage fury of the raiders, the wrath invoked in them by pious upstarts with their new Christian God. Easier perhaps is to imagine the dread that must have been felt by the monks as the Vikings approached their spiritual eyrie.

Without doubt this was a life of supreme hardship: the isolation, the relentless diet of fish and seabird eggs, the ever-battering wind and salt-spray. Such was the isolation, and so extreme the privations of this beatific pursuit, that one might assume that the monks would have been left in peace to practice their calling. This was not to be. Viking raiders arrived here in the early 9th century and took the trouble to land, scale the island’s heights and attack the monks. For most of us it is probably difficult to comprehend the blind-rage fury of the raiders, the wrath invoked in them by pious upstarts with their new Christian God. Easier perhaps is to imagine the dread that must have been felt by the monks as the Vikings approached their spiritual eyrie.

The small city of Kruševac in south-central Serbia is probably best known for its fortress and 14th-century church, a fine example of the highly decorative Morava school. This was Prince Lazar’s capital in the late 14th century and it was from here that the Serbian army under the command of Prince Lazar set off to fight the ill-fated Battle of Kosovo in 1389. The Turks won yet it still took another 60 or so years for the city to fall under Ottoman control. Later on Kruševac became known as the ‘city of the sock-wearers (čarapani)’ because of an incident during the First National Uprising when Serbian rebels removed their boots to slip silently into town at night unheeded by the Turkish guards. Today Kruševac is an easy-going sort of place that, church aside, serves as a textbook case of Tito-era urban planning with its extensive use of concrete and scattered high-rises that loom like grey termite mounds over the city centre.

The small city of Kruševac in south-central Serbia is probably best known for its fortress and 14th-century church, a fine example of the highly decorative Morava school. This was Prince Lazar’s capital in the late 14th century and it was from here that the Serbian army under the command of Prince Lazar set off to fight the ill-fated Battle of Kosovo in 1389. The Turks won yet it still took another 60 or so years for the city to fall under Ottoman control. Later on Kruševac became known as the ‘city of the sock-wearers (čarapani)’ because of an incident during the First National Uprising when Serbian rebels removed their boots to slip silently into town at night unheeded by the Turkish guards. Today Kruševac is an easy-going sort of place that, church aside, serves as a textbook case of Tito-era urban planning with its extensive use of concrete and scattered high-rises that loom like grey termite mounds over the city centre.  This was my third visit in a decade and on this occasion I was prompted to seek out something that I had hitherto not even been aware of. A short distance out of town to the south lies a monument park dedicated to the victims of Nazi shootings during World War II. This was close to a former German prison camp and the scene of mass shootings between 1941—4, most especially in the summer of 1943 when over a thousand Serbs partisans and civilians were executed mostly by Bulgarian and Albanian troops. The Slobodište Memorial Complex, designed in the early 1960’s by architect, politician, one-time Belgrade mayor and anti-nationalist critic of Slobodan Milošević, Bogdan Bogdanović (1922—2010), occupies the same low hill just outside the city where the killings took place. The monuments of the complex serve as focus for a location already tainted with dark memory and collective suffering.

This was my third visit in a decade and on this occasion I was prompted to seek out something that I had hitherto not even been aware of. A short distance out of town to the south lies a monument park dedicated to the victims of Nazi shootings during World War II. This was close to a former German prison camp and the scene of mass shootings between 1941—4, most especially in the summer of 1943 when over a thousand Serbs partisans and civilians were executed mostly by Bulgarian and Albanian troops. The Slobodište Memorial Complex, designed in the early 1960’s by architect, politician, one-time Belgrade mayor and anti-nationalist critic of Slobodan Milošević, Bogdan Bogdanović (1922—2010), occupies the same low hill just outside the city where the killings took place. The monuments of the complex serve as focus for a location already tainted with dark memory and collective suffering.  The monument park is reached on foot by way of a route through Kruševac’s outskirts. The city edgeland arrives suddenly: a roundabout, a small airfield marked by a jet fighter on a plinth, an out-of-town retail hangar with supersized advertising depicting super-fit sportsmen. As elsewhere in Serbia, the edgeland is the realm of Roma – the poorest of the poor in this none-too-wealthy country – who, as always, are involved in the recycling business. Perpetually sorting through waste – paper, metal, plastic – skilfully assessing its value, their make-do shanty shelters seem barely separated from the middens of 21st-century detritus that they live among.

The monument park is reached on foot by way of a route through Kruševac’s outskirts. The city edgeland arrives suddenly: a roundabout, a small airfield marked by a jet fighter on a plinth, an out-of-town retail hangar with supersized advertising depicting super-fit sportsmen. As elsewhere in Serbia, the edgeland is the realm of Roma – the poorest of the poor in this none-too-wealthy country – who, as always, are involved in the recycling business. Perpetually sorting through waste – paper, metal, plastic – skilfully assessing its value, their make-do shanty shelters seem barely separated from the middens of 21st-century detritus that they live among. At first there is nothing to see other than landscaped grassy mounds in the distance. Walking through a birch plantation I am entertained by the head-cracking antics of a Syrian woodpecker that hammers away remorselessly at a tree stump. Crows in all their variety – rooks, jackdaws, magpies and jays – call harshly, their voices like creaking tree trunks in a gale. I make for the grassy mound ahead and from the top can see a curved chain of stone sculptures stretched up the hollow of a hillside. The monuments resemble birds – owls to be precise – buried up to their beaks in the earth, but rising from rather than sinking down into it. They might also be angels. As I walk closer to investigate I notice a man with a bicycle at the top of the rise who is waving and beckoning to me. We manage some sort of rudimentary conversation using an inelegant polyglot mixture of German, Serbian and what might be Russian, and I learn that he lives locally in one of the housing estates that fringe the park and uses its pathways as a shortcut to the shops.

At first there is nothing to see other than landscaped grassy mounds in the distance. Walking through a birch plantation I am entertained by the head-cracking antics of a Syrian woodpecker that hammers away remorselessly at a tree stump. Crows in all their variety – rooks, jackdaws, magpies and jays – call harshly, their voices like creaking tree trunks in a gale. I make for the grassy mound ahead and from the top can see a curved chain of stone sculptures stretched up the hollow of a hillside. The monuments resemble birds – owls to be precise – buried up to their beaks in the earth, but rising from rather than sinking down into it. They might also be angels. As I walk closer to investigate I notice a man with a bicycle at the top of the rise who is waving and beckoning to me. We manage some sort of rudimentary conversation using an inelegant polyglot mixture of German, Serbian and what might be Russian, and I learn that he lives locally in one of the housing estates that fringe the park and uses its pathways as a shortcut to the shops.  Conversation, and commonality of language, exhausted the man cycles off and I turn round to trace the pathway back to its beginning. What is actually supposed to be the entrance to the memorial complex – the ‘Gate of the Sun’ – serves as my exit: an incomplete arch reminiscent of an Andy Goldsworthy dry-stone creation. Flanking the entrance just beyond this are two pyramidal mounds like Neolithic cairns. In front of each is a low stone funerary slab upon which rest wreaths and polythene-wrapped flowers. Whether or not these are actual burial mounds or merely a symbolical representation does not really seem to matter – this whole site is a memory field of death and the act of remembrance is the important thing. And remembered it is: memory is honoured; this site still holds melancholic charge for townsfolk and visitors alike despite its mundane use as a place for cycling, exercising and walking dogs.

Conversation, and commonality of language, exhausted the man cycles off and I turn round to trace the pathway back to its beginning. What is actually supposed to be the entrance to the memorial complex – the ‘Gate of the Sun’ – serves as my exit: an incomplete arch reminiscent of an Andy Goldsworthy dry-stone creation. Flanking the entrance just beyond this are two pyramidal mounds like Neolithic cairns. In front of each is a low stone funerary slab upon which rest wreaths and polythene-wrapped flowers. Whether or not these are actual burial mounds or merely a symbolical representation does not really seem to matter – this whole site is a memory field of death and the act of remembrance is the important thing. And remembered it is: memory is honoured; this site still holds melancholic charge for townsfolk and visitors alike despite its mundane use as a place for cycling, exercising and walking dogs. There is one more monument to see: the cenotaph. I find a curious, vaguely zoomorphic statue that brings to mind a Mayan glyph, or a totem – or perhaps another owl. It stands alone and inscrutable in front of some administrative offices that have been landscaped into the naturalistic contours of the park. Within one of the offices I spot a man working on a computer. I cannot decide whether I am envious of his workplace or not. No doubt it is peaceful enough tucked away in the folds of this green domain but the heft of dark memory weighs heavy here – a place to visit certainly but not one in which to repose.

There is one more monument to see: the cenotaph. I find a curious, vaguely zoomorphic statue that brings to mind a Mayan glyph, or a totem – or perhaps another owl. It stands alone and inscrutable in front of some administrative offices that have been landscaped into the naturalistic contours of the park. Within one of the offices I spot a man working on a computer. I cannot decide whether I am envious of his workplace or not. No doubt it is peaceful enough tucked away in the folds of this green domain but the heft of dark memory weighs heavy here – a place to visit certainly but not one in which to repose.

I set out from Kessingland, just south of Lowestoft, where a large expanse of dunes and shingle separates the sea from the holiday homes and caravans that line the low clifftop like racing cars at a starting grid preparing to rush towards the sea. Truth be told, there is little in the way to stop them. It may be August but even now the beach is relatively quiet – just a few families and dog-walkers clambering over the dunes to reach the sea, which today is grey, grumpy and not particularly welcoming. The Kessingland littoral is distinguished by its specialist salt-tolerant flora: sea holly, sea pea, sea campion, sea beet – in fact, place a ‘sea’ in front of any common plant name and there is a good chance that such a species will exist and flourish here. Also rooted into the shingle, thriving on little more than sunshine and salt spray, are clumps of yellow-horned poppies with long twisting seed pods. The poppies are mostly past their flowering peak but elsewhere, where there is a thin veneer of soil to root into, colour is provided by stands of rosebay willow herb – a rich purple layer of distraction between the straw-hued shingle and the cloud-heavy sky, both washed of colour in the flat coastal light.

I set out from Kessingland, just south of Lowestoft, where a large expanse of dunes and shingle separates the sea from the holiday homes and caravans that line the low clifftop like racing cars at a starting grid preparing to rush towards the sea. Truth be told, there is little in the way to stop them. It may be August but even now the beach is relatively quiet – just a few families and dog-walkers clambering over the dunes to reach the sea, which today is grey, grumpy and not particularly welcoming. The Kessingland littoral is distinguished by its specialist salt-tolerant flora: sea holly, sea pea, sea campion, sea beet – in fact, place a ‘sea’ in front of any common plant name and there is a good chance that such a species will exist and flourish here. Also rooted into the shingle, thriving on little more than sunshine and salt spray, are clumps of yellow-horned poppies with long twisting seed pods. The poppies are mostly past their flowering peak but elsewhere, where there is a thin veneer of soil to root into, colour is provided by stands of rosebay willow herb – a rich purple layer of distraction between the straw-hued shingle and the cloud-heavy sky, both washed of colour in the flat coastal light.  Further south, the cliffs grow a little higher. Ferrous red and as soft and powdery as halva, they are irredeemably at the mercy of the North Sea tide. And it shows: the cliffs are raw and freshly cleaved, with collapsed chunks that have been further eroded by the incoming tide such that they appear to seep from the cliff bases like congealed gravy. Man-made objects receive no preferential treatment – a collapsed WWII concrete defence bunker slopes between cliff and sand at one point, its long process of total disintegration still in its infancy as its perches ignominiously at 45 degrees, an involuntary buttress for the flaking cliffs.

Further south, the cliffs grow a little higher. Ferrous red and as soft and powdery as halva, they are irredeemably at the mercy of the North Sea tide. And it shows: the cliffs are raw and freshly cleaved, with collapsed chunks that have been further eroded by the incoming tide such that they appear to seep from the cliff bases like congealed gravy. Man-made objects receive no preferential treatment – a collapsed WWII concrete defence bunker slopes between cliff and sand at one point, its long process of total disintegration still in its infancy as its perches ignominiously at 45 degrees, an involuntary buttress for the flaking cliffs.

This was bear country. No doubt about it. Over breakfast Alfred from the guesthouse had said, “You should make sure that you talk when you go walking there – or maybe sing – that way you won’t take them by surprise. My wife and I saw a mother bear with cubs in those woods earlier this year but don’t worry too much, just make sure that you don’t take them by surprise.”

This was bear country. No doubt about it. Over breakfast Alfred from the guesthouse had said, “You should make sure that you talk when you go walking there – or maybe sing – that way you won’t take them by surprise. My wife and I saw a mother bear with cubs in those woods earlier this year but don’t worry too much, just make sure that you don’t take them by surprise.” The drizzle had stopped by the time we left the guesthouse to walk east along the bank of the Valbona River. The day before we had come across four snakes in the space of a couple of hours, including a sluggish horn-nosed viper that had the tail of an unfortunate lizard protruding from its mouth, but today, perhaps because of the lack of warm sunshine, they were nowhere to be seen. Undoubtedly they were still close by, skulking beneath rocks, sleeping the deep reptilian sleep that comes with the digestion of a heavy meal… of reptiles. No snakes, but we did see an extraordinary large lizard – a European green lizard (Lacerta viridis) as we later identified it – with strikingly beautiful markings that morphed like a potter’s glaze from sky blue on the head to copper-stain green along its back and tail. Among our fellow guests at the guesthouse were a couple of German amateur herpetologists and, confronted by reptilian magnificence as this, it was easy to understand the appeal. Bear country it may have been but this was snake and lizard territory too.

The drizzle had stopped by the time we left the guesthouse to walk east along the bank of the Valbona River. The day before we had come across four snakes in the space of a couple of hours, including a sluggish horn-nosed viper that had the tail of an unfortunate lizard protruding from its mouth, but today, perhaps because of the lack of warm sunshine, they were nowhere to be seen. Undoubtedly they were still close by, skulking beneath rocks, sleeping the deep reptilian sleep that comes with the digestion of a heavy meal… of reptiles. No snakes, but we did see an extraordinary large lizard – a European green lizard (Lacerta viridis) as we later identified it – with strikingly beautiful markings that morphed like a potter’s glaze from sky blue on the head to copper-stain green along its back and tail. Among our fellow guests at the guesthouse were a couple of German amateur herpetologists and, confronted by reptilian magnificence as this, it was easy to understand the appeal. Bear country it may have been but this was snake and lizard territory too. In a meadow just beyond the footbridge that led across the racing river to the tiny hamlet of Čerem, stood a monument to Bajram Curri. Bajram Curri (pronounced ‘Tsuri’ like the English county rather than the universal Indian dish) also gave his moniker to the principal market town of this far northern border region of Albania, its name only 20 years ago a watchword for lawlessness and gun-running – a KLA stronghold that was more closely connected to what was then war-torn Kosovo than its own national capital in Tirana. These days, Bajram Curri is a quiet provincial town that only ever becomes animated on market days when hard-bargaining farmers might raise their voices over the price of sheep. Like the rest of Albania, it is now as safe as anywhere in Europe – safer probably – yet still there were those who looked askance whenever Albania was mentioned as if the country was still lawless and dangerous and run by shady mafia figures. It is not… but there are bears in the woods.

In a meadow just beyond the footbridge that led across the racing river to the tiny hamlet of Čerem, stood a monument to Bajram Curri. Bajram Curri (pronounced ‘Tsuri’ like the English county rather than the universal Indian dish) also gave his moniker to the principal market town of this far northern border region of Albania, its name only 20 years ago a watchword for lawlessness and gun-running – a KLA stronghold that was more closely connected to what was then war-torn Kosovo than its own national capital in Tirana. These days, Bajram Curri is a quiet provincial town that only ever becomes animated on market days when hard-bargaining farmers might raise their voices over the price of sheep. Like the rest of Albania, it is now as safe as anywhere in Europe – safer probably – yet still there were those who looked askance whenever Albania was mentioned as if the country was still lawless and dangerous and run by shady mafia figures. It is not… but there are bears in the woods. Further on a wooden sign pointed steeply uphill towards ‘The Cave of Bajram Curri’, the cave where the Albanian hero and patriot was said to have once taken refuge whilst fleeing his enemies. We followed this up through woodland for a short while before taking another path to the left that signposted the springs at Burumi i Picamelit. This track, marked by occasional red and white ciphers painted on trees like Polish flags, lead through dense beech woodland scattered with huge boulders that had long ago thundered down from the cliffs far above. It was an evocative place, a numinous realm of shade and fecundity – the light tinged green by filtration through the high leaf canopy and by the thick carpet of moss that coated every surface. Here and there were saprophytic ghost orchids poking through the coppery leaf mold – pale, bloodless plants that had no truck with the chlorophyll that otherwise permeated the woodland like a green miasma.

Further on a wooden sign pointed steeply uphill towards ‘The Cave of Bajram Curri’, the cave where the Albanian hero and patriot was said to have once taken refuge whilst fleeing his enemies. We followed this up through woodland for a short while before taking another path to the left that signposted the springs at Burumi i Picamelit. This track, marked by occasional red and white ciphers painted on trees like Polish flags, lead through dense beech woodland scattered with huge boulders that had long ago thundered down from the cliffs far above. It was an evocative place, a numinous realm of shade and fecundity – the light tinged green by filtration through the high leaf canopy and by the thick carpet of moss that coated every surface. Here and there were saprophytic ghost orchids poking through the coppery leaf mold – pale, bloodless plants that had no truck with the chlorophyll that otherwise permeated the woodland like a green miasma. The path eventually bypassed a glade where large moss- and fern-covered rocks formed a natural outdoor theatre. Dead dry branches snapped noisily underfoot as we made our way across to the largest of the rocks – silence was not an option and any lurking bears would have been duly warned of our intrusion by our clumsy, crunching progress. Growing high on one of the larger rocks was a solitary Ramonda plant, a small blue flower and rosette of leaves anchored to the moss. The plant had an air of rarity about it – and scarce it was: a member of a specialised family found only in the Balkans and Pyrenees. Growing in solitary isolation and providing a discrete focal point in this hidden glade it almost felt as if this delicate blue flower had lured us here – the trophy of a secret quest, an object of worship. Indeed, the whole glade had the feel of the sacred: an animist shrine or secret gathering place; the location for a parliament of bears perhaps?

The path eventually bypassed a glade where large moss- and fern-covered rocks formed a natural outdoor theatre. Dead dry branches snapped noisily underfoot as we made our way across to the largest of the rocks – silence was not an option and any lurking bears would have been duly warned of our intrusion by our clumsy, crunching progress. Growing high on one of the larger rocks was a solitary Ramonda plant, a small blue flower and rosette of leaves anchored to the moss. The plant had an air of rarity about it – and scarce it was: a member of a specialised family found only in the Balkans and Pyrenees. Growing in solitary isolation and providing a discrete focal point in this hidden glade it almost felt as if this delicate blue flower had lured us here – the trophy of a secret quest, an object of worship. Indeed, the whole glade had the feel of the sacred: an animist shrine or secret gathering place; the location for a parliament of bears perhaps? We looked for evidence of ‘bear trees’ and eventually we found it: beside the track we discovered a conifer that had a large patch of bark missing from its trunk, freshly removed by the action of claw sharpening – or maybe as some sort of territorial signifier. At the junction of tracks further on was more visceral evidence in the form of a footpath sign that has been quite brutally attacked by a bear (or bears), the support post whittled away to a fraction of its former girth by unseen fearsome claws. Why this post had more bear-appeal than live growing trees of similar size was a mystery. Did bears have a preference for scratching away at machined timber? Was the unnatural square profile of the post especially tempting? Or did the bears somehow understand what signposts were for – to direct clod-footed human walkers into their territory. Fanciful and absurdly anthropomorphic though this might seem it did somehow hint at a thinly disguised warning – a re-purposing of man-made signposts to advertise the bears’ own potential threat: ursine semiotics. The day had, of course, been characterised by a total absence of bears – and woodpeckers too, despite numerous dead trunks riddled with their excavated holes – but their unseen presence in this secretive bosky world was nonetheless all too tangible. All the signs were there to be read.

We looked for evidence of ‘bear trees’ and eventually we found it: beside the track we discovered a conifer that had a large patch of bark missing from its trunk, freshly removed by the action of claw sharpening – or maybe as some sort of territorial signifier. At the junction of tracks further on was more visceral evidence in the form of a footpath sign that has been quite brutally attacked by a bear (or bears), the support post whittled away to a fraction of its former girth by unseen fearsome claws. Why this post had more bear-appeal than live growing trees of similar size was a mystery. Did bears have a preference for scratching away at machined timber? Was the unnatural square profile of the post especially tempting? Or did the bears somehow understand what signposts were for – to direct clod-footed human walkers into their territory. Fanciful and absurdly anthropomorphic though this might seem it did somehow hint at a thinly disguised warning – a re-purposing of man-made signposts to advertise the bears’ own potential threat: ursine semiotics. The day had, of course, been characterised by a total absence of bears – and woodpeckers too, despite numerous dead trunks riddled with their excavated holes – but their unseen presence in this secretive bosky world was nonetheless all too tangible. All the signs were there to be read.

We ventured on to visit the springs at Burumi i Picamelit where underground water emerged straight from the limestone to race downhill in a fury towards the Valbona River below. Tucked away in a crevice beneath one of the rocks was another Ramonda growing just inches from the fast-flowing water.

We ventured on to visit the springs at Burumi i Picamelit where underground water emerged straight from the limestone to race downhill in a fury towards the Valbona River below. Tucked away in a crevice beneath one of the rocks was another Ramonda growing just inches from the fast-flowing water. Heading back we become temporarily lost in the woods and spend ten minutes walking in circles looking for the trail before finally rediscovering it. Shortly after, we met the German reptile enthusiasts from the guesthouse walking the other way. We stopped to compare notes. None of us had seen any sign of bears in the flesh (in the fur?) but we had all seen the evidence that beckoned us: the claw-scratched trees, the mauled signpost. We concurred that it was probably best that way: an absence of bears on the ground but a strong sense of their presence as we politely trespassed their territory.

Heading back we become temporarily lost in the woods and spend ten minutes walking in circles looking for the trail before finally rediscovering it. Shortly after, we met the German reptile enthusiasts from the guesthouse walking the other way. We stopped to compare notes. None of us had seen any sign of bears in the flesh (in the fur?) but we had all seen the evidence that beckoned us: the claw-scratched trees, the mauled signpost. We concurred that it was probably best that way: an absence of bears on the ground but a strong sense of their presence as we politely trespassed their territory.

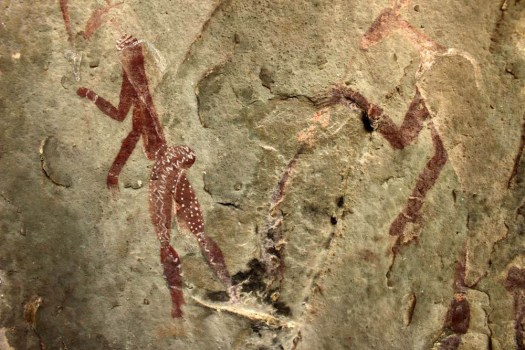

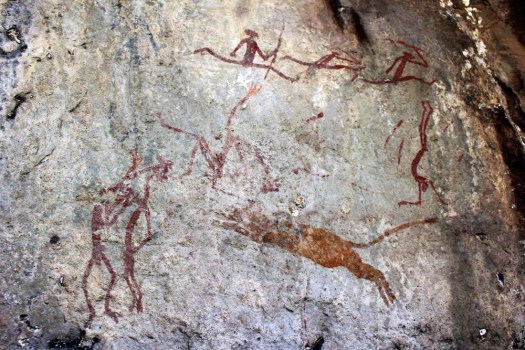

One of the highlights of my recent trip to South Africa was to see some really well-preserved rock art. The cave paintings were made by the San people, the hunter-gatherers who inhabited the Drakensberg mountain region in KwaZulu-Natal province close to the Lesotho border before the incoming Zulus drove them from the land. The rock paintings date from between 2,000 and 200 years ago and the best preserved are those found in south-facing caves where there is never any direct sunlight. One such cave is that found beneath Lower Mushroom Rock in the central Drakensberg.

One of the highlights of my recent trip to South Africa was to see some really well-preserved rock art. The cave paintings were made by the San people, the hunter-gatherers who inhabited the Drakensberg mountain region in KwaZulu-Natal province close to the Lesotho border before the incoming Zulus drove them from the land. The rock paintings date from between 2,000 and 200 years ago and the best preserved are those found in south-facing caves where there is never any direct sunlight. One such cave is that found beneath Lower Mushroom Rock in the central Drakensberg. The figures show hunting scenes involving various animals indigenous to the region, like eland, which are still numerous, and lions, which are no longer found here. Other paintings depict animal skin-wearing shamans in trances, a state of mind artificially (and partially chemically) induced to connect them with the spirit world in order to foresee the future and cure illnesses.