My new book Flint Country: a stone journey will be published on July 10th. Here’s a link to the blog post I wrote about it for the publisher, Saraband.

Hidden places, secret histories and unsung geography from the east of England and beyond

The road to Dirē Dawa is a long one: an eight-hour drive from Addis Ababa, or so we are told.

We left Addis Ababa at dawn, our bus rattling through empty streets shadowed by new-build office blocks. As with almost everywhere currently in Ethiopia, the pavements were piled with concrete rubble, the result of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s ambitious nationwide road-widening project, a controversial scheme that had already demolished parts of some poorer city districts and displaced many residents in its wake.

For the first hour or so we sped along a pristine tarmacked dual carriageway, the brightening horizon ahead weighed down by clouds the colour of watermelon juice. We could have been almost anywhere; or, at least, anywhere that comes blessed with a backdrop of purple-shadowed mountains and lush tropical greenery. Eventually the freeway morphed into a narrow two-lane highway, which meandered around the heads of valleys as we plied our way eastwards. Traffic was heavy in both directions. Coming towards us was an endless stream of heavily laden trucks from Djibouti, each one towing a trailer, vehicle and driver bonded in lockstep like driven cattle. We slotted into a gap in the fast moving crocodile of trucks that were heading east towards the coast, some of which were piggybacking another truck strapped to their flatbed.

As elsewhere in the country there were checkpoints and roadblocks to slow things down. We had already experienced these travelling the roads of the south, especially in Oromia state, although they had rarely delayed us for long. Sometimes they were administered by the Ethiopian army but more often than not they were manned by local militia who wanted to keep an eye on who was coming into their territory. It had not taken long in the country to come to the conclusion that, rather than the unified sense of national identity promoted by the government, Ethiopia was in the process of becoming increasingly fragmented by region, language, culture and political persuasion.

Before our arrival in Ethiopia we had made firm decisions as to our itinerary. These were based on information gleaned from online travel forums and British FCO warnings regarding more unstable areas of the country. Much of the north – the highlands of Amhara and part of Tigray – was considered unsafe because of rebel activity and kidnappings. Similarly, part of the large sprawling region of Oromia that fans south, west and east from Addis Ababa also came with similar warnings about safety. The FCO had produced a map of the country that divided the country into three zones according to perceived safety: red (‘Advise against all travel’), amber (‘Advise against all but essential travel’) and green (‘see our travel advice before travelling’). I had consulted the updated map frequently throughout the second half of 2024 in the vain hope that brotherly love might prevail throughout the land but the map did not appear to change very much. Much of the south, in particularly the area around Hawassa where we had spent the previous week, was largely amber and therefore considered relatively safe. The highway between Addis Ababa and Dirē Dawa appeared to pass through both amber and green zones, nudging the red briefly between the Oromia towns of Welenchiti and Metehara.

Road blocks and heavy traffic aside, the other barrier to easy progress was roaming animals – donkeys, goats and camels. The donkeys especially were a law unto themselves, totally unfazed by the vehicles that swerved around them as they pottered along oblivious to any danger. It seemed almost as if the animals understood the fast and loose rules of the road – fully aware that if they were harmed then their owners would require compensation from the guilty driver. On a couple of occasions I actually saw one cross the road using a zebra crossing. Camels were a different matter though, large enough to call the shots, they were generally unwilling to step aside or allow any vehicle to manoeuvre past them.

We passed through an endless parade of villages that had little to differentiate themselves from one other: a blurred flash-by of roadside settlements, all flimsy housing and lean-do shops thrown together out of scrap wood, plastic sheets and corrugated iron. The goods on sale – fruit and vegetables, flyblown meat, second hand clothes, spare parts for vehicles – were the bread and butter (or, perhaps, injera) of everyday life. As always in the Global South, it was intriguing how such a base-level financial system managed to thrive, a poor man’s economy in which ragged ten birr notes continually changed hands until all the value had been squeezed out of them.

There was another product on sale that seemed to be ubiquitous in this part of the world – we had seen it on display along almost every roadside in southern Ethiopia the previous week. Khat, the stimulant of choice across much of the Horn of Africa, is an innocuous looking leaf that resembles bay or privet. Legal throughout the region, khat is, as many Ethiopians will attest, less a stimulant, more a way of life. Our driver was clearly an aficionado; as was our guide, a young man who kept his own counsel throughout the journey and did not utter a word of information about the foreign (to us) country that lay beyond the window. The pair just stared ahead for the whole way, locked in herbal reverie as they slowly worked through the pile of leaves that lay at their elbow.

Khat seems to be very much a driving drug, an herbal alternative to the so-called energy drinks whose slim cans over-caffeinated motorists toss out of their windows along Britain’s motorways. It might even be considered to be a green alternative to caffeine, although there is absolutely no shortage of coffee in this land of stay-awake plenty. A week earlier, motoring through the coffee-rich Sidama region of the south, our previous guide, Wonde (‘Wander’), had regaled us with horror stories about khat-crazed drivers careering off the road due to lack of sleep and/or poor decision-making. It seemed perfectly believable. Between Addis and Dirē Dawa I counted at least eight trucks that had crashed and gone off-the-road; some lay forlornly on their side, while others had ended up completely upside down with wheels akimbo. It was unclear as to what had become of the drivers, although it did not look as if they would have escaped unscathed.

One crashed truck that we passed had unleashed a load of crated beer bottles onto the slope beside the road. Slowing down to make our way around the crowd that had gathered around the wrecked vehicle, the air smelled as malty as a Sunday morning pub. A couple of armed men were guarding the booty as approved wreckers sifted through the debris, placing the unbroken bottles in crates ready for resale. Who the men with guns were was anybody’s guess. It was the same at some of the checkpoints we were obliged to stop at, where youths with rifles peered inside the bus before lowering the barrier – no more than a rope stretched across the road – to allow us to pass. A single word from the driver, ‘Turist’, and a glance at our pale well-fed faces within, was usually sufficient for us to be waved on.

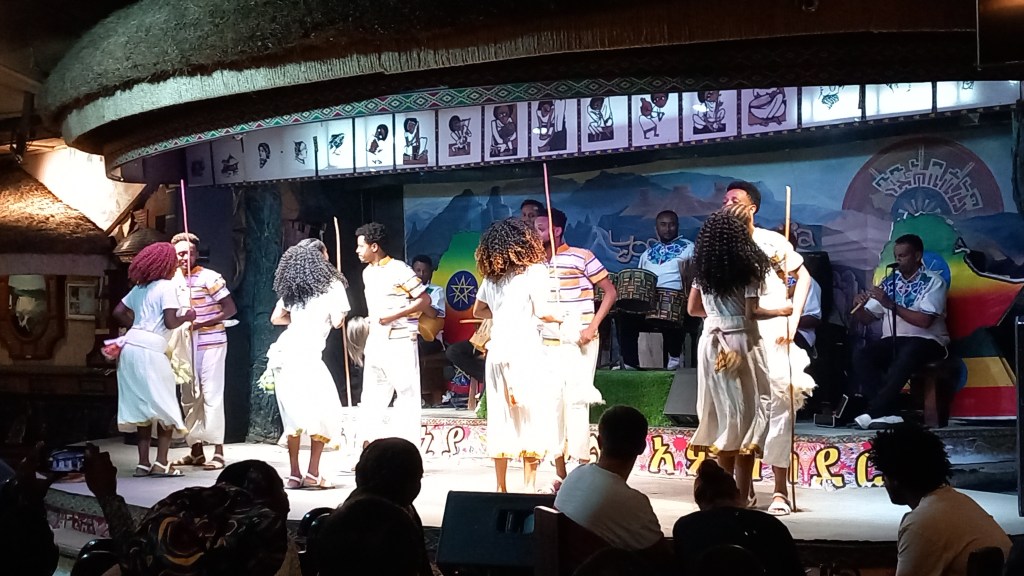

While khat consumption is widespread, it was something that was shared with other countries in the region like Somalia. Other aspects of Ethiopian culture are decidedly more unique. One is the country’s unorthodox calendar, which is seven or eight years behind the rest of the world. While the year elsewhere might be 2024 according to the Gregorian calendar, in Ethiopia it is currently 2017. ‘Welcome to Ethiopia, and congratulations,’ we had been told more than once, ‘here you are seven years younger.’ Another Ethiopian curiosity is the music that is played loud and proud almost everywhere, which whether traditional, pop, or the rather wonderful Ethio-Jazz that I had already developed a taste for, uses a pentatonic scale that has a distinctive modal sound to it. A world away from other African music that is generally more accessible to Western ears, Ethiopian music has a tendency to sound rather other-worldly and even a little Chinese at times.

Another facet of Ethiopian culture that sets the country apart is the food, which is quite unlike anywhere else. The mainstay of the diet is a sour spongy pancake called injera, which is made from an ancient indigenous grain called teff. This is eaten along with small helpings of spicy vegetable or meat sauces. For many Ethiopians, if they can afford it, kitfo (spicy raw beef) is the preferred accompaniment, although, perhaps counter-intuitively, there are actually two days of the week, Wednesday and Friday, when restaurants are obliged to serve only ‘fasting’ food, which is strictly vegan. Whether meat or vegetable, raw or cooked, freshness is probably the most important factor in regards to health, and I believe it was the suspicious, rather tired-looking sauce that came with the injera I had eaten the previous night in Addis that had been the cause of the stomach cramps that troubled me throughout the long journey.

We pulled into Dirē Dawa just as it was becoming dark, the onset of the city’s flickering neon countering the rapid tropical plunge into night. The journey had taken twelve hours – sunrise to sunset. Considerably lower in altitude than where we had come from, the city felt hot and humid compared to Addis’s fresher, spring-like climate. But it was as bustling and noisy as the capital, with a honking stream of three–wheel bajajs (tuk-tuks) plying Dirē Dawa’s wide boulevards. Tomorrow there would be the opportunity to visit the city’s sights, such as they were. Tonight though, after a day of unremitting motion, it was the promise of laying still on an immobile bed that held the greatest appeal.

A Journey to Avebury is the name of a short silent film made by Derek Jarman made in 1971. Shot in wobbly Super 8, and saturated with burnt orange hues, it has an otherworldly eldritch atmosphere that is hard to describe. Suffice to say it is hardly be the sort of thing that the then English Tourist Board might have chosen to promote the stone-encircled Wiltshire village. Too painterly and surreal by half for such considerations, the film is both beautiful and slightly disturbing, and has the feel of a psychedelic adventure about to go wrong. With wind-blown trees and shifting clouds against Martian skies, A Journey to Avebury evokes the strangeness of a landscape that is already inherently deeply weird. The weirdness owes much to the implacable monoliths that dominate the village, although Jarman’s focus on the rolling Wiltshire landscape that surrounds the village, with its bare fields and isolated clumps of trees, is equally suggestive of a territory that exists outside the usual constraints of time and space.

Avebury is undoubtedly an extraordinary place – a village that not only lies at the heart of a sacred Neolithic landscape but one that uniquely sits within the sweep of a stone circle. Not surprisingly it is a much visited location, especially in the summer months, as visitors that range from newly retired to New Age travellers come to walk the circle of stones and pay tribute to this ancient, stone-bound place. After several visits to the village myself, its megaliths and raised banks, pathways and lanes have become firmly imprinted in my mind. Some places fade quickly but Avebury is somewhere that etches itself on the memory.

Even in prehistoric, monument-rich Wiltshire, Avebury has a particular gravity. It feels as if it is at the centre of things, a focal point for the megalith-strewn landscape that surrounds it. Nearby are other, even older monuments that put the stone circle and avenues of Avebury into context: the destroyed stone and timber circle of The Sanctuary, the chambered West Kennet Long Barrow and, most remarkable of all, the man-made chalk Mount Fuji that is Silbury Hill. These are all connected, by footpaths, tracks and, as many believe, ley lines, although it is the monument of Avebury that gives the impression of lying at the beating heart of it all.

Visiting Avebury is like going to meet an old friend from the past. Last summer, I did just that: arranging to meet a friend whom I had not seen for decades at the village. We sat at a bench in the churchyard of and reminisced about shared memories from forty years ago. Time stretched and compressed obligingly – but perhaps the location helped.

Like Stonehenge, the megaliths of Avebury were likely associated with ritual and social gatherings. They may also have functioned as some sort of solar calendar. But if Avebury is a place of measured time, it is also a place that stands outside time. The past, present and future rest easy here, although in the right light the village with its New Age atmosphere can appear to be perpetually locked in the 1970s – perhaps 1971, the same year that Jarman came here to make his film.

A Journey to Avebury (1971) by Derek Jarman

Also, this excellent fantasy drama TV series for children, broadcast on ITV in 1977, was filmed almost entirely at Avebury. Children of the Stones by Jeremy Burnham and Trevor Ray

Now, with the promise of autumn in the air, it feels almost nostalgic to look back on those hot days of just two months ago: the end of July, record temperatures; the countryside baked and arid. A visit then, to Dungeness on the Kent coast, a headland jutting out to sea just to the east of the Sussex border. One of the largest expanses of shingle in Europe, it is a fabled place. Hitherto unknown, my only reference points are those places closer to home like Norfolk’s Blakeney Point and Suffolk’s Sizewell and Orford Ness where, until recently at least, there was a lighthouse. Dungeness, I learn, has two – an old and a new; like Sizewell, there is a nuclear power station. Like both, there is shingle galore.

The modern mythology of Dungeness precedes it. Much of it is connected with the filmmaker Derek Jarman, who lived here in a fisherman’s cottage in the 1990s. We arrived on what was predicted to be the hottest day on record and stayed overnight at a B&B on the coast road at nearby Lydd-on-Sea. The shelved beach was entirely of pebbles, nearly all flint, most of which were black although some were a warm shade of amber. I clambered awkwardly across loose, sun-blasted stones to take a swim, glad of the water’s relative coolness. The sea was tepid mulligatawny, warmed by the incoming tide flowing over hot pebbles. Across the bay lay the white low-rise of Folkestone, and beyond this Dover’s celebrated cliffs. Later, when the air cleared a little, we could see Boulogne gleaming across the Channel. Boulogne-sur-Mer: another country, closer here than even the horizon, although we, as a nation, were allowing it to drift from view. The water, the English Channel, had become both a salty barrier that kept us apart us as well as a fluid channel that connected us. The French, always better dressed, call it La Manche, ‘the sleeve’. Language has its own agenda; language slips from tongues and connives to confuse – La Manche: c’est la mer. La Manche: c’est le mur. La France: c’est l’amour.

The next day really was the hottest day on record. We drove to Dungeness to find Jarman’s house. Prospect Cottage, black-painted wood with bright yellow window frames, looked to be in excellent condition. The cottage was close enough to Dungeness Power Station to be within the acoustic shadow of the menacing clang and whir of its machinery. The garden was clearly a work of love, a metaphor for Jarman’s dwindling years, an exercise in making the most of limitations: a temple to pebbles and the salt-tolerant flora that would grow in their presence – sea kale, yellow-horned poppy, red valerian, fennel and clumps of tough spiky grasses. Beach debris, like sea-bleached driftwood, provided makeshift statuary, while circles of larger pebbles were arranged like henges. Unlike most gardens it seemed an extension of the landscape rather than any sort of imposition on it. Here on a bleak shingle spit, framed by the terrifying machinery of nuclear fusion, was, as the title of Jarman’s book suggests, modern nature.

We drove on past the red and white banded new lighthouse to a pub close to the old lighthouse and the power station – the Britannia Inn (‘Fish & Chips, Pizza’), which had trestle tables lined up outside in its car park that afforded unbroken views to the concrete edifices of Dungeness B. It was hard to imagine something that could simultaneously be both so English and so weirdly incongruous. Signs in the shingle across the road warned of the necessity of a licence for filming and photography in specific areas. Like Orford Ness in Suffolk, Dungeness has become a brand with associated commercial interests. Membership cards of any psychogeographic-inclined affiliation were invalid here.

A boardwalk led across the shingle to a bench. Coming along it back towards the road were two policeman carrying binoculars. We had already noticed a large police presence in the area – patrol cars, transit vans with anti-riot shields poised above windscreen. At first, perhaps naively, I had thought it was a matter of security – keeping an eye on the power station, an obvious if not particularly vulnerable target for would-be terrorists. Then it dawned that they were here to watch the sea for migrant rafts. France was at its closest here and the English Channel was about as calm as it ever gets. It was high season for people smuggling.

Some of the houses that lined Marine Drive in Lydd had first floor balconies that looked out to sea. A few had flagpoles with flapping St George or Union flags. Here at England’s south-eastern edge, the Continental ‘other’ in plain view, expressions of nationalism appeared to be defiant and full-throated. I wondered what sort of welcome any raft voyager who successfully beached here would receive from those who had seen them approach through the telescope mounted on their verandas. Somehow I doubted that many would have the kettle boiling and the Hobnobs ready on a plate.

Dungeness’s watchfulness is nothing new. In the heat of the first afternoon I had taken a walk to see the Denge sound mirrors located on an island in what had recently been designated an RSPB reserve. Now designated Scheduled Ancient Monuments, the sound mirrors, constructed of concrete in three radically different designs, were built between 1928—1935 and were an intriguing precursor to the invention of radar just before World War II. Strange objects to find in any landscape let along here among the shingle and marshes of the West Kent littoral, the idea was that they would detect the sound coming emanated by low-flying enemy aircraft coming across the channel – an early warning system of ‘Listening Ears’ as they became known.

It was a historical fact, dictated by location and landscape, that Dungeness had long been keeping its ears and eyes open to intruders from across the sea. If such liminal places were ever to participate in a twinning scheme then Orford Ness in Suffolk, with its secret bomb testing facilities and comparable edge of the world atmosphere, would be a natural contender. Both Dungeness and Orford Ness watch and listen as the flint pebbles grind and roll on their beaches in ever-shifting Heraclitean flux. Panta rhei: ever moving, never the same, always the same.

For one week this June this small island off the Antrim coast was a constant presence. The cottage we had rented stood high on a hill a couple of miles outside the resort of Ballycastle and the view to the north was an uninterrupted panorama of sea, sky and the long, low profile of Northern Ireland’s only inhabited island. The view depended on the weather, of course, which was something that changed constantly and wavered between overcast and mixed spells of sunshine and showers.

The L-shaped island that hugged the northern horizon was always visible, although in less clement weather it was sometimes little more than a hazy grey outline, a vague smudge that sat on the water. Sun or shine, two of the island’s three lighthouses were always in view, winking at intervals to alert shipping – the waters around Rathlin Island have a long history of shipwrecks and the remains of many unsuspecting vessels lie gathering barnacles at the bottom of the Atlantic close to its shore.

On sunnier days, more detail became evident and the island’s magpie cliffs of basalt and chalk could be clearly discerned, as could the houses and church of the village by the harbour. It was on these brighter days that other landforms also took shape on the horizon. Most days we could make out the southern end of the Scottish peninsula that is the Mull of Kintyre but now and then, far beyond the island, more distant places came into view – the hills of Islay and the unmistakable rise of the Paps of Jura.

From our perspective the island appeared to be at the edge of things. The most northerly point in Northern Ireland, it was the place where the island of Ireland gave way to the Atlantic. A small island that lay off the coast of another larger island, it seemed to be more an outlier than a stepping stone to anywhere else. But it was a place that had not always been so peripheral: long before today’s national divisions had come into play Rathlin had been central to the ancient Gaelic kingdom of Dal Riada, a political entity that included the coast of Argyll in western Scotland as well as part of what is now County Antrim in Northern Ireland.

Some days we could make out the ferry, Spirit of Rathlin, plying its way between Ballycastle and the island. On a day that promised to be calmer and sunnier than most we made the journey ourselves. As we drew closer to the harbour at Rathlin an increasing number of seabirds could be seen bobbing about on the water – a taste of what we would soon be seeing on the island itself. These were mostly guillemots but there were also small parties of gannets flying low over the waves, identifiable even at distance with their butter-coloured necks and long ink-dipped wings.

At Rathlin harbour, a bus – the ‘Puffin Express’ – was waiting to drive passengers across the island to the RSPB bird reserve at its western point. Here, steps led down to a viewing platform opposite the cliffs and stacks where the seabirds nested. The malodorous smell of guano grew increasingly strong as we descended – observing seabirds up close is undoubtedly one of the least glamorous aspects of bird watching. From the viewing platform vast numbers of seabirds could be seen at their nests opposite on the rocks – as closely packed as an urban high-rise but with distinctly separate enclaves of guillemot and razorbill, kittiwake and puffin. Closer to the viewing platform, a few fulmars, contemptuous of the excitable human presence and unperturbed by the relentless glint of expensive optics, had made their nests in the grass just beyond the barrier.

Driving back to the village, past fields of sheep and grazing cattle, our driver stopped the bus briefly to point out a cave to our left. It was the entrance, he said, to the stone axe mine that had existed on the island in Neolithic times.

In Belfast, a few days earlier, I had gone to see the so-called Malone Hoard at the Ulster Museum. The hoard was a collection of 19 beautifully polished stone axes that had been discovered on Malone Road close to the museum. The axes were around 6,000 years old and clearly ceremonial objects of some kind: not only were they too large to be of practical use for chopping trees but when they were discovered some of the stones had been found aligned vertically in the ground. Even behind glass, they were undeniably beautiful objects and had a curvy heft about them that seemed to invite handling. Given the understandable restrictions imposed by museums, this, of course, was not possible.

The axes had been identified as being made from a rock called porcellanite, a hard, dense impure variety of chert so-named because of its physical similarity to unglazed porcelain. Unlike flint, porcellanite does not flake easily and has a texture that accepts a fine polish and keen edge. There were only two possible sources of this scarce rock in Northern Ireland. Both were in Antrim. One was at Tievebulliagh, a 402-metre mountain in the Glens of Antrim; the other was on Rathlin Island. Both sources yielded rock of exactly the same physical and chemical makeup so it was impossible to tell which had been used for the Malone Road axes. For reasons of romance rather than anything more scientific, I preferred to think that these precious objects had originated here on the island.

Back off the bus, we sat on the beach at Mill Bay listening to the piping of oystercatchers and watching grey seals as they made forays through the rafts of seaweed that lay just offshore. Seaweed was once a profitable business here. A little further on towards the harbour, an abandoned kelp barn stood roofless next to the shore. It was built of blocks of the same Cretaceous chalk that make up the white cliffs we could see from our rental cottage on the mainland.

After an unproductive listen for corncrakes in a field we had been told about by an RSPB warden we made our way to the jetty to wait for the ferry back to Ballycastle. Notwithstanding the lack of corncrakes, it had been a satisfying few hours. We were by now brim-full with all the wonders that Rathlin Island had to offer: the seabirds – the smell, the noise, the frantic flying about; the wider natural history of the place – the seals, the kelp, the garden flowers that had gone feral and colonised the island’s dry stone walls. Then there was the geology – the Cretaceous chalk and Tertiary basalt of the cliffs, the flints on the beach, the cave with its supply of elusive porcellanite. It would have been nice to have taken a peek inside the cave where the stone axe mine had been but it did not really matter. Prehistory, myth and memory are all intertwined and we make our own emotional truths. Whatever the true archaeological facts of it, in my mind at least the Malone Hoard axes would always be associated with this place on the edge of things.

Stoke Newington, London N6. We are here to walk part of the Capital Ring that circuits the capital by way of 15 stages. Slightly perversely we decide to begin at Stage 13, which links Stoke Newington with Hackney Wick by means of a park and a path alongside the River Lea and Lea River Navigation. Less defiantly, we will follow the overall route clockwise as suggested. To go widdershins might be an enticement but we are civilised men not maniacs.

Firstly though, Abney Park cemetery beckons. The main Egyptian Gate on the high street is closed but there is a way round the side that funnels us between barriers into the non-conformist boneyard. The park, as much arboretum as cemetery, is quiet – dense foliage neutralising the din of traffic from the roads that surround it; just a few muffled barks from exercising dogs and the jungle shriek of an unseen parakeet. Quiet or not, the tree-lined paths are fairly busy with strollers and dog-walkers. We come across one woman who has no less than seven small lead-dragging dogs in her charge, including a one-eyed pooch that clearly bears a grudge against binocular humans.

We have no purpose or aim other than just to wander and take it all in – the trees, the gravestones, the gothic atmosphere, the knowledge that this cemetery was the inspiration for the hidden fragment of Paradise that Arthur Machen wrote about in his short story N. We find no such paradise garden but instead plenty of interesting angel-perched tombs and several oddities – a wooden marker that asserts mysteriously ‘Elvis put his hand on my shoulder’ and the simple stone gravestone with the legend: ‘Thomas Caulker 1846—1859 Son of the King of Bompey’. Bompey, we later discover, was an early 19th century West African chiefdom that was eventually incorporated into Sierra Leone in 1888. The stone looks like a fairly modern replacement. What is curious is that the 160-year-old grave is still attended – a single flower has been recently placed upon it.

We exit the park to join the Ring; a sign right outside the cemetery confirms we are on the right path. My companion Nigel takes a photograph of me in front of the sign and as he does this a cheerful Black woman pushing an empty shopping trolley offers to take a snap of the two of us – she assumes we are tourists, and in many ways she is right. We head up Cazenove Road, where a fading ghost sign on a gable advertises a discontinued brand of whisky and an abandoned charity shop, as niche as you like, boasts a Bosnia & Herzegovina connection. It is all comfortingly multicultural – orthodox Jewish men in black hats and long coats rub shoulders with Muslims in white skullcaps and shalwar kameez. Looking at our map to check the route, one of the latter, a helpful elderly Pakistani, asks if we need directions and points us towards Springfield Park. There is no denying it – we really do look like tourists.

At the rise of the park the Lea Valley suddenly comes into view beyond – a proper valley, a river-carved ha-ha that slopes down to the water and sharply up again. A sign at a viewpoint helpfully informs us that we are standing on Hackney gravel, below that is London clay. Another parakeet screeches, this one perched in a tree, lurid green, channeling the tropics.

A more at home, native species – a heron – stands guard on a houseboat close to the footbridge at the bottom of the park. It sees us but looks unperturbed. We cross over the river to the east bank and start walking south. Walthamstow Marsh stretches away to the east, all reed, sedge and soggy pasture; rising above the marsh, beyond the railway, stands an island of modern development that may or may not be offices. There is an almost endless line of houseboats moored to both banks. Nothing too chi-chi – vaguely counter-cultural but mostly no-nonsense make do and mend: heaps of burner firewood, car batteries, plants in plots, well-used bicycles; a few seasoned boat dwellers going about daily chores, clenched roll-ups, dreadlocks piled high.

Across the water, a little further along, is a pub with outside trestle tables stacked for winter: The Anchor & Hope. Not the Hope & Anchor, the historic pub rock venue in Islington that we remember hearing tales of in our youth. Anchor & Hope – Anchor (or at least moor) and Hope your boat doesn’t sink? Anger and Hope maybe? There seems to be plenty of anger about but hope can be elusive; as they say, it is the hope that kills.

Approaching Clapham Junction Viaduct we hear the two-stroke put-put of a barge on the move. Another barge comes from the rear to slowly overtake and the two boatmen exchange chummy bargee greetings as they pass on the water. A sign under the viaduct arches indicates that this is the original location of A V Roe’s workshop where the first all-British powered flying craft, a precarious-looking tri-plane held together with wire and glue, was built in 1909. Inspired by the Wright Brothers’ achievement of just six years earlier, the aeronaut successfully managed a short wobbling flight across the adjacent marshes, a sight that must have given the local herons quite a start.

At Lea Valley Ice Centre the path diverts along the canalised Lea River Navigation, the wide green expanse of Hackney Marshes stretching invitingly to our left. We detour briefly to view the former site of the Middlesex Filter Beds, now a designated nature reserve, where we find the granite blocks that once held the pumping engine in place rearranged into what has become known as the ‘Ackney Enge’. A little further on we find the hope we had been looking for back at the waterside pub: a footbridge over the water has a draped banner that proclaims BELIEVE IN OUR COLLECTIVE IMAGINATION on one side, and on the other, DARE TO DREAM BEYOND CAPITALISM. Hope indeed.

Shortly before reaching Hackney Wick we pass beneath a roadway where the supporting concrete arches have been comprehensively decorated with all manner of found objects – bottle tops, cans, bits of wire, keys, keyboards, electronic components, beer cans – all lovingly glued in place and spray-painted. As I stop to take a photograph, a man on a bike appears out of nowhere to inform me that the artist, a lovely fellow by all accounts, was a friend of his who had died quite recently. He pedals off back into the shadows as quickly as he arrived. Then I notice a portrait of the artist attached to the second of the pillars. The artist in question looks remarkably like the man I have just spoken to. Could this be a ghost artist obliged to return and show visitors around his urban art gallery, a revenant on a bicycle?

Our walk ends at Hackney Wick. We know we have arrived when we see West Ham’s London Stadium at Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in the distance, the deranged helter-skelter of Anish Kapoor’s ArcelorMittal Orbit alongside it. Somewhat disoriented by the glare of the new development that engulfs us on all sides, we look for the bus stop we need for the service back to central London. I know that it is close to the Church of St Mary at Eton but its location proves to be elusive. My A to Z is well out of date, the streets marked on it have since been redacted; new ones with new names have taken their place. Nigel employs his smart phone to engage with a satellite to find the correct route and we beat a path past Hackney Wick Overground station and along streets parallel to the thrumming A12. Despite the nearby traffic frenzy, the area is relatively quiet and uncluttered by commerce, just a scattering of car body repair shops and the occasional cafe. A random sign offers sourdough pizza – you can almost hear self-respecting Neapolitans crying in anguish. But nothing is sacred and change is inevitable: the deeply layered lasagne that is East London has had its time-honoured béchamel topping scraped away and replaced with something considered to be more wholesome. As ever, the city is a palimpsest.

A warm, slightly hazy day on the north Norfolk coast; a day caught on the cusp as an unusually cold spring stumbles into an, as yet unknown, summer. We walk west past a few lobster boats from the beach car park at Cley-next-the-Sea, scrunching through the shingle to reach a meandering path that leads through low glaucous shrubs at the edge of a salt marsh. Just beyond the shingle ridge to our right is the North Sea, a constant mineral grumble of pebbles grinding on the tide; an aural massage – maritime poetry in motion. In the distance ahead, a solitary single–storey building, ‘Halfway House’, cuts a lonely figure in the landscape. Beyond this, in the murky haze at the very end of the Point, is the bright blue of the onetime lifeboat station that now serves as a visitor centre.

So what’s the point? Or rather, where is the Point? Blakeney Point is a shingle spit that begins at Cley Beach and extends like a claw nearly four miles to the west, the result of centuries of longshore drift piling up sand and stone to create new land. Although famous for its breeding population of harbour and grey seals, we are here today for its little terns, which nest at awkward and not particularly sensible places in the shingle leaving their eggs vulnerable to high tides and attack by opportunist predators like gulls and kestrels. Our friend Hanne is one of several volunteers responsible for keeping an eye on the birds.

A cordoned-off area of shingle encloses some of the tern’s nests, although many by now have moved on west to the end of the Point. There are oystercatchers too, and avocets – each species doing its best to mind its own business. Salt-tolerant plants like sea beet, sea campion and biting stonecrop are all anchored in the firmer shingle, while at the looser-stoned apex of the ridge that slopes steeply down to the water seakale is in full bloom. Elsewhere, clumps of yellow horned poppy, another shingle specialist, are starting to throw up flower heads in readiness for blooming. A place that instinctively you feel should be barren; it seems remarkable that anything can grow here nurtured by little else but stone, sand and saltwater.

Hanne takes us for a walk up towards Halfway House. A skylark sings high overhead, little more than a high fidgeting dot to the naked eye. In the distance, across the marshes close to Blakeney Channel, we catch sight of the unmistakable form of a marsh harrier quartering the reed beds. On the Point itself the bushes are alive with restless flittering birds that turn out to be a mixture of meadow pipits, linnets and reed buntings, although at times of migration almost anything could turn up here. And it does: as first point of landfall for any bird carried unwittingly by powerful winds from the north, Blakeney Point has an impressive record of rare sightings.

Our most impressive sight by far, though, is a meeting with a brown hare – or, rather, a pair. One of them makes a run for it and disappears into the Suaeda (shrubby sea-blite), the other remains, frozen in its tracks, hunched with long ears flattened to its head in an effort to make itself small. In some ways more resembling a small deer than a large rabbit, with improbably long ears and soft, intelligent eyes, it is easy to see how hares have always been revered in British and European folklore. Long gifted magical properties by those whose livelihood affords them a close relationship to the soil, hares engender a strong sense of ‘the other’: a sacred animal, a spirit familiar, a symbol of fecundity, sex and madness. A means of divination too: the Iceni warrior queen Boudicca is said to have read the entrails of a hare as an augury for victory against the Romans in her uprising of AD61.

The hare slowly adjusts to our presence and cautiously and slowly raises its ears, then straightens its legs before finally bolting off to join its companion. Our serendipitous encounter has been no more than a minute in total but the whole incident has put a temporal brake on the space-time continuum. As the hare moves off, time – at least the quotidian linear time that embraces cause and effect – is finally unfrozen.

We continue our walk to head down a wide swath of firm shingle and sea thrift that Hanne calls the Fairway. It leads to the edge of a tidal creek close to Halfway House. The highly prized real estate of Blakeney village is clearly visible across the channel that separates us from the ‘mainland’, as is St Nicholas’ church high above the houses and, west of this, the iconic windmill at Cley. In the network of creeks and mudflats that fringe the channel, redshanks alternate between stabbing the mud in search of invertebrates and flying short distances, calling plaintively as they go. At the muddy margins, marsh samphire is starting to emerge, although it is still too early to pick. Heading back to the car park, we walk along the sloping beach alongside the outgoing tide. Beyond the silhouetted fishing boats ahead, the distant cliffs of West Runton are visible in the sea-hazed distance. Just pure sea-sound now: no motor vehicles or human voices, just the swash of waves on pebbles, the piercing cry of terns and the aerial clatter of a skylark beyond the ridge to our right.

Many thanks to Hanne Siebers and Klausbernd Vollmar for their company on the Point. Check out Hanne’s wonderful photographs of Casper, Cley’s leucistic barn owl at The Silent Hunter

The isolated Calvinist Methodist chapel of Soar-y-mynydd is often claimed to be the remotest in all of Wales. Certainly, it lies in a very quiet spot: close to the eastern limit of Ceredigion, eight miles southeast of Tregaron within the parish of Llanddewi Brefi (of Little Britain fame)

Built in 1822 to serve a widely scattered congregation of farmers and sheep drovers, it would have originally stood close to the road to Llandovery that followed the Cammdwr valley south. Like many other central Welsh valleys, this was flooded in the 1970s to provide a reservoir that now extends close to where the chapel stands.

Despite its relative isolation the chapel has seen illustrious visitors over the years. Many poets and artists have been inspired by its whitewashed simplicity and even former US President Jimmy Carter was impressed when he visited on a fishing holiday in 1986. (A painting of the chapel by Ceredigion artist Wynne Melville Jones was subsequently presented to the former president in appreciation of his visit.)

The chapel interior is simple, not exactly austere but unfussy: tightly packed wooden benches dappled with red and blue light from the Mondrian-esque stained glass; plain walls that seem to resonate with earnest drovers’ prayers and ancient Welsh voices. On one of the walls a painted scroll bears the simplest of messages: Duw cariad yw (‘God is love’).

Ferris wheel, Toktogul, Kyrgyzstan

Ferris wheel, Toktogul, Kyrgyzstan

One of the enduring images from Pripyat, the main town in Ukraine’s Chernobyl disaster region, is that of an abandoned amusement park. A totem for the fall from innocence, here are rides that children once played upon but will never do so again. Rising above the park is an abandoned yellow Ferris wheel – a dejected structure that has fallen in grace from a onetime wheel of fun and joy to a symbol of nuclear catastrophe.

At one time Ferris wheels could found in most Soviet towns of a certain size. One former SSR state I know better than most is the central Asian republic of Kyrgyzstan, a country named after the once-nomadic people indigenous to the region. With three revolutions now since its independence in 1991, it is classic example of a territory in transition, a new country of arbitrarily imposed political boundaries that is still trying to find its feet.

View of Manas Square from Bishkek Ferris wheel, Kyrgyzstan

View of Manas Square from Bishkek Ferris wheel, Kyrgyzstan

To my knowledge there are at least four Ferris wheels that stand in Kyrgyzstan today, although there may be more. The one in Panfilov Park in the heart of the Kyrgyz capital Bishkek has been upgraded in recent years to replace the somewhat creakier Soviet-era one that stood before. Kyrgyzstan’s second city of Osh in the south of the country has another. This Ferris wheel is older (and a little cheaper) than its Bishkek rival and stands in a city park close to the rather desultory canalised river that flows through the city. Alongside the wheel is decommissioned Aeroflot Yak-40 that has been repurposed as a children’s playground. Both Bishkek and Osh wheels afford excellent city views for an outlay of just a few Kyrgyz som.

Panfilov Park, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

Panfilov Park, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

There is another wheel, said to be the largest in the country, in the resort of Bosteri on the north shore of Lake Issyk-Kul but the other Kyrgyzstan Ferris wheel that I have personal experience of can be found in the small town of Toktogul halfway between Bishkek and Osh. Skeletal and long abandoned, this one is found at the edge of a leafy park next to a crumbing sports stadium. Old-fashioned fairground rides can still be found in some of the clearings; the wheel, though, no longer turns. With its seats removed – for their scrap value presumably – and left to the attention of the elements, the wheel, framed against the blue central Asian sky, evokes an air of melancholia. Argumentative crows perpetually flock around the structure as if it had always been theirs to inhabit, taunting its immobility with wheeling flight. At one time this over-sized bicycle wheel delighted children and adults alike with its thrilling views of Toktogul Reservoir and the snow-capped peaks of the Fergana mountains beyond. Now it is a wheel that no longer wheels; a rusting reminder of a half-forgotten past unknown to the children who visit the park today.

Crows and abandoned Ferris wheel, Toktogul, Kyrgyzstan

All photographs ©Laurence Mitchell

If you are curious to discover more about Kyrgyzstan you might want to try this…

There is a bar in Belgrade called the World Traveller’s Club. It is in the basement of an apartment block in the city centre and to gain entrance you are required to ring the door bell at street level and state your business over the intercom. These days the club, which is alternatively known as the Federal Association of Globetrotters, is just one of many quirky bars in the city – homespun decor, art school daubings on the walls, miscellaneous furniture that includes Singer trestle sewing machines for tables, posters of iconic foreign destinations like Paris and Rome. The bar, as it proudly declares on its menu, was established in 1999. The date is significant.

In 1999 Belgrade was the capital of a land still known as Yugoslavia, a much depleted country that by that stage of the breakup consisted of just Serbia, Montenegro and Kosovo. Internationally, the country was considered as a pariah state thanks to the continuing ultra-nationalist regime of Slobodan Milošević. 1999 was also the year that NATO bombs fell on Belgrade and other Serbian cities. It was neither a good place to be nor somewhere that was easy to escape from – a Yugoslav passport, once a document that allowed easy access to both West and Eastern bloc, no longer held any currency. Such a document would get you nowhere.

It goes without saying that not everybody in Serbia was happy with Milošević’s stubborn and didactic rule. Most young people in Belgrade just wanted to do what young people did everywhere – live, love, make mistakes, have fun, travel. Many of these were still possible to some extent but travel was clearly out of the question. As a reaction to this difficult state of affairs a few people came together to create the World Traveller’s Club, a safe welcoming environment where people could meet to travel in their imagination if not in real space. Initially membership was by invitation only. These days anyone can visit although the bar’s original purpose no longer holds much significance other than a reminder of difficult times.

Turn the clock back thirty years, back to a time when foreign journeys required a wider leap of the imagination. In the pre-Internet age any inspiration for travel for its own sake was dependent on books, photographs and the anecdotes of others. In the 1970 film Performance, the Turner character, a reclusive rock star played by Mick Jagger as a caricatured version of himself, reads aloud from a Persian text, The Old Man of the Mountains. A postcard is displayed entitled The Mountains of Persia. Both text and image represent a sort of paradise – that which is unattainable, a dream destination for the two men thrown together in self-isolation in Turner’s Notting Hill Gate basement. Turner is living as a recluse, hiding from fame and perhaps the fear that his powers are diminishing; Chas, the James Fox character, is keeping a low profile to avoid the attention of fellow gangsters. The idealised mountains of Persia represent a sanctuary where both men might manage to escape their past lives.

The curtailment of free movement as in late 1990s Yugoslavia is hard to imagine these days. Many of us in the developed world take travel for granted almost as a birthright. This is especially true in an age in which jet travel is both cheap and easily available, and a journey, a holiday or even an off-the-peg adventure, can be booked with the click of a return key. Now, suddenly, in the light of a rapidly worsening pandemic, we need to think anew. We must accept that for a while at least, probably some considerable time, we are not going anywhere. Perhaps now is the time to form our own fraternities and sororities of imagined exploration? Any globetrotting must be virtual and digital. For the foreseeable future wanderlust is going to be just that, a lust for something unattainable. In this respect I am lucky I suppose. For a number of reasons, in recent years I have come round to thinking that it is just as fruitful to explore my own backyard as it is any exotic far-flung destination. I have grown weary of airports and the mechanical human processing that takes place, the tiresome, albeit necessary, security measures. As B. B. King sang of another sort of love affair, The Thrill Is Gone. The notion of ‘slow travel’ and all that it represents has for me become something that has gone beyond simply an attractive-sounding travel franchise. These days I really do prefer to slow down, to cover a smaller area, to discover the beauty of the local, to chart the quotidian. Less is undoubtedly more but that is easy to say for someone like me who already has the T-shirts, the passport stamps, the photographs, the anecdotes, the well-thumbed guidebooks on the shelves.

In the plague-year situation that the world now finds itself in to complain about restricted movement seems, at the very least, churlish. As we enter what seems like late capitalism’s final closing down sale (‘Everything Must Go!’) we have become, as the columnist Marina Warner has recently written, ‘a nation of shopfighters’. While shoppers squabble over toilet paper in supermarket aisles and some wealthier hoarders, like newly arrived Beaker folk mocking the simple ways of those who still rely on cupped hands, purchase additional freezers for the storage of their panic-shopped supplies, we should maybe reflect on what we (or, rather, some of us) have become. It is an opportunity perhaps to show a little more respect to the land that we walk upon, for the earth that feeds us; a little more kindness to those we share it with. For the time being we can just look out of the window and dream. At the other end of all this the mountains of Persia will still be there.

Photographs: Karakhanad, Yazd region, Iran 2008 ©Laurence Mitchell