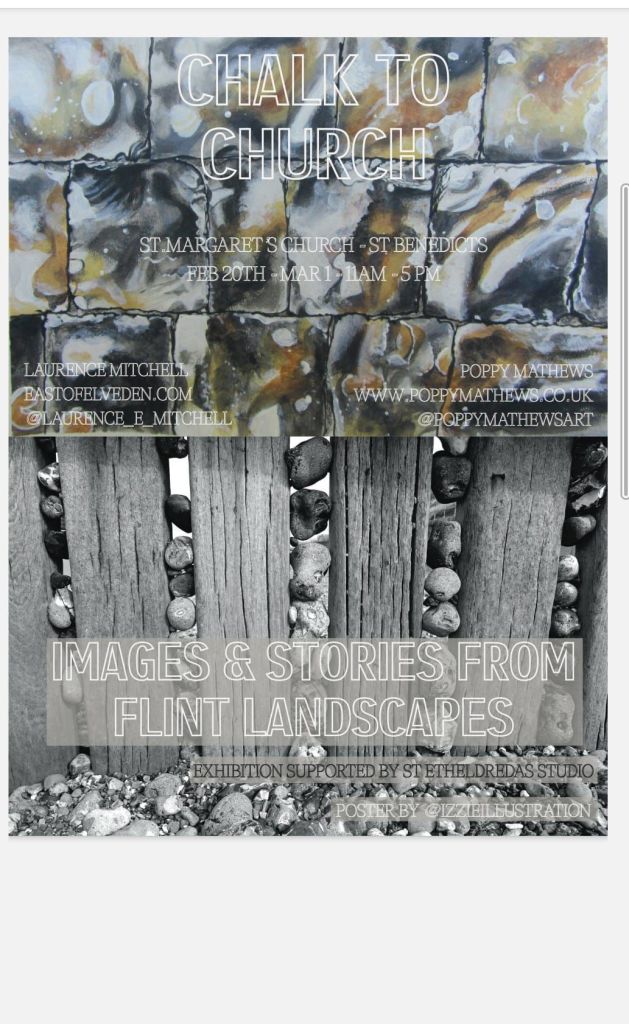

I am currently involved in an art exhibition at St Margaret’s Gallery, St Benedicts St, Norwich. The exhibition is mixed media, with paintings by Poppy Mathews (@poppymathewsart) and photographs and text by me. It is all very flint-themed and, for my part at least, relates closely to my recent book. Some of the text is taken from the book, Flint Country; some was written specifically for the exhibition.

Here is a small sample of what you can see at the exhibition. Of course, if you just happen to find yourself in the Norwich area over the next week then please drop in to have a look. Chalk to Church is open 11.00-17.00 daily and will run until Sunday, March 1st.

Flint 1 – Poppy Mathews

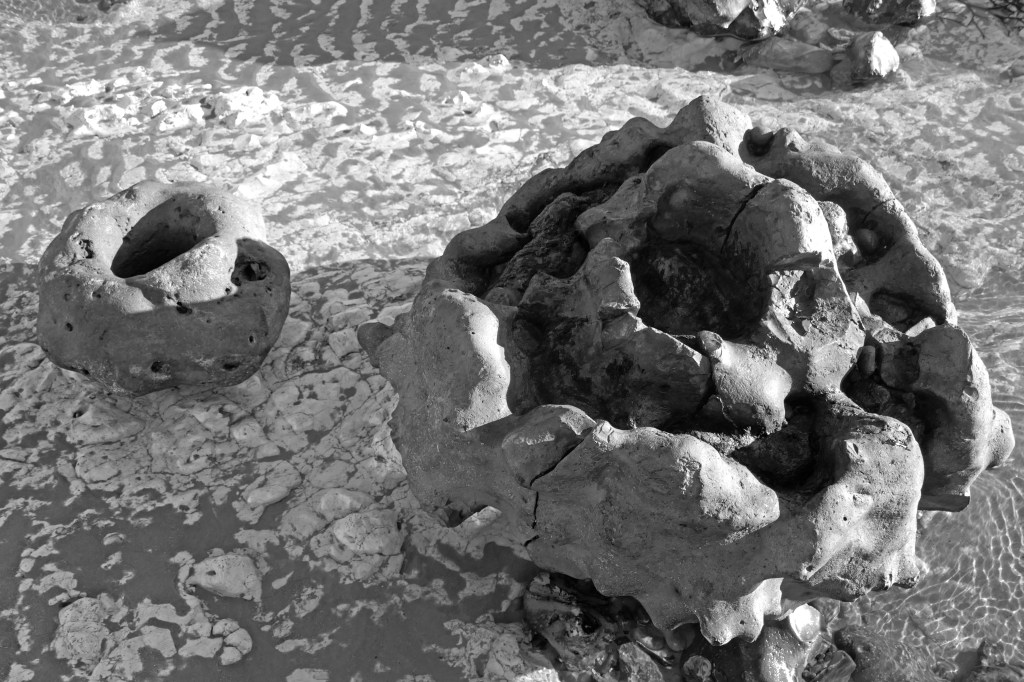

Paramoudras, West Runton Beach, Norfolk

Flint sometimes naturally takes the shape of a nest-like structure in the form of a paramoudra. It is the sort of nest that you might imagine a small dragon laying a clutch of eggs in.

Many of the larger flints that lay scattered were paramoudra – tubular in shape and either hollow in the middle or filled with chalk like a sculptured vol-au-vent.

The name paramoudra is Irish, deriving from the Gaelic peura muireach, meaning ‘sea pears’. They have also been called ‘ugly Paddies’ in the past, which seems a little harsh, even racist. They are beautiful in their own way. Their Norfolk name of ‘potstones’ makes more sense, as some of the better formed ones could easily be adapted to serve as plant containers. Paramoudra, like all flints, are actually pseudofossils. They are generally thought to be fossilised barrel sponges but the precise process of their formation is not fully understood.

Flint Country

Orford Ness, Suffolk

A warning, its message lost to the shingle

Stray Cold War ordnance? Or tide?

This secret place, its geography both cause and effect

A zone of intrigue, longshore drift and flint music

Liminal, littoral, literal

A spit that resembles an island yet is called a ‘ness’ – an Anglo-Saxon word for ‘nose’ that describes a headland or promontory – Orford Ness is a luminous landscape of shingle, birds and secrecy. A one-time top secret weapons testing site, it continues to exude an air of secrecy sufficient to make even the modern-day visitor feel as if that they are standing on forbidden territory. Its former exclusion from the public gaze is now part of its appeal but, even without this, Orford Ness is a highly evocative sort of place. In recent years, the spit’s unique combination of dark history and melancholy landscape has resulted in it becoming a holy ground for a particularly niche variety of art and literature. All have tried to tap into the Ness’s peculiar genius loci.

Flint Country

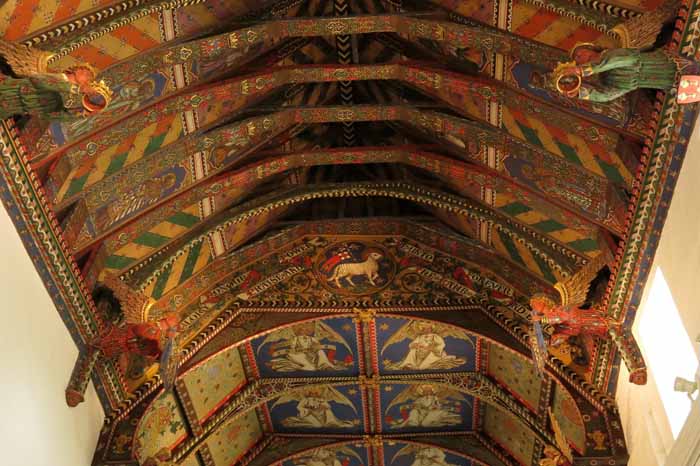

Guildhall – Poppy Mathews

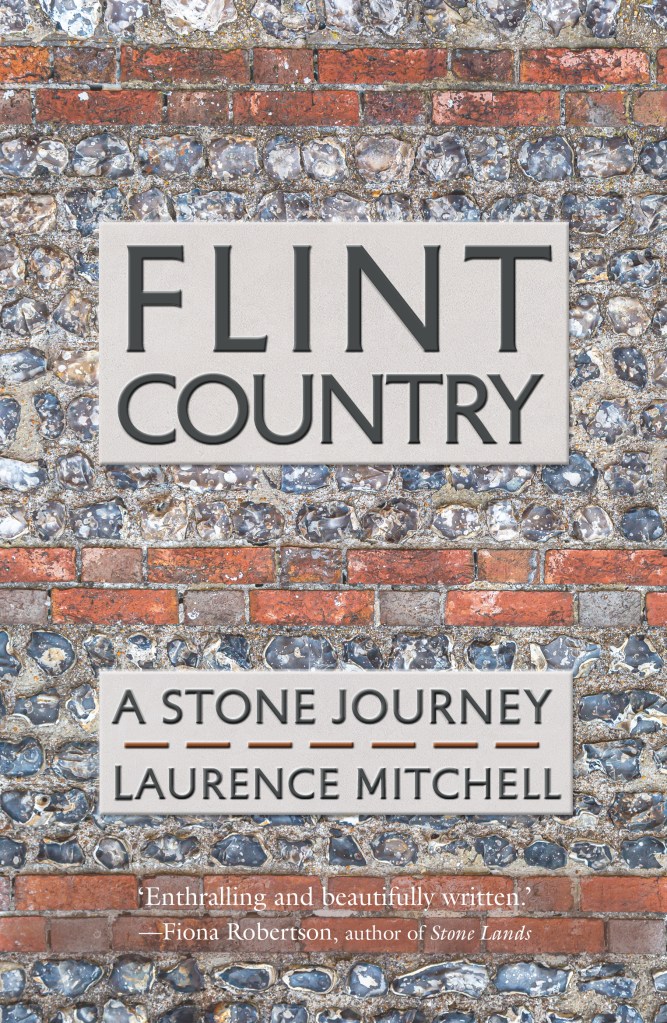

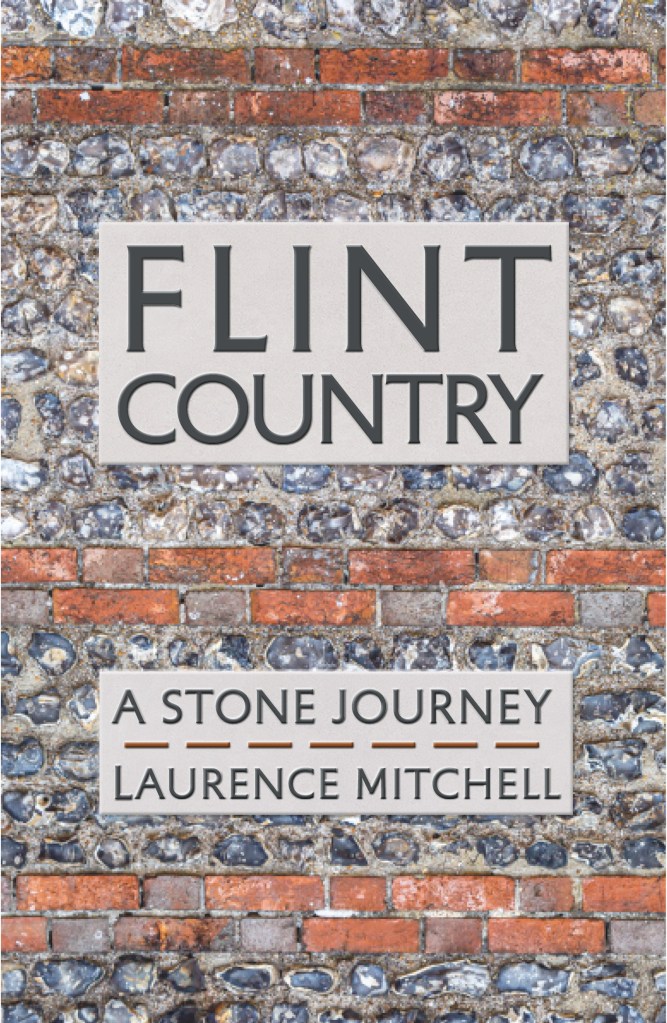

Flint wall, Museum of Norwich at the Bridewell

A night-black wall, early medieval

Its joints, Inca-snug, four-square

Yet not quite square

A thousand faces to the world, a mosaic of time-lost oceans

Visitors to Norwich have long noted the abundance and splendour of its flint buildings. The equestrian traveller Celia Fiennes visiting the city in 1698 observed that Norwich, in addition to having ‘a great number of dissenters’ was ‘a rich, thriving industrious place’:

… by one of the churches there is a wall made of flints that is headed very finely and cut so exactly square and even to shut in one to another that the whole wall is made without cement at all they say… it looks well, very smooth shining and black.

The building whose wall Celia Fiennes was so impressed with still stands and for almost a century has served as the city’s Bridewell Museum. As the plaque by the museum entrance confirms, it has long been considered ‘the finest piece of flintwork in England’.

Flint Country

Ruin of St Mary’s Church, Saxlingham Thorpe, Norfolk

Given sufficient time, ruins can blend into the landscape and accumulate folklore along with the ivy and bramble. A ruin invariably provokes a sense of melancholy – a psychological linkage of place and emotion that has been recognised since antiquity. There is even an Old English word for it: dustsceawung, which translates as ‘the contemplation of dust’, although ‘dust’ here should be considered in the broader sense of that which remains after destruction, along with the concomitant awareness that all things go this way eventually.

Norfolk has more than its fair share of ruins. In particular, it abounds with a wealth of long-abandoned flint-built churches. Mostly these ended up as ruins because of abandonment and their subsequent deterioration over the centuries that followed. Others were deliberately dismantled, partially at least for the building stone they held, which would then be recycled for use in new churches, houses and farm buildings.

Flint Country

Flint 5 – Poppy Mathews

The Saints is a small, loosely defined area of northeast Suffolk just south of the River Waveney and the Norfolk border. Effectively it is a fairly unremarkable patch of arable countryside that contains within it a baker’s dozen of small villages with names that begin or end with the name of the parish saint: St Peter South Elmham, St Michael South Elmham, St Nicholas South Elmham, St James South Elmham, St Margaret South Elmham, St Mary South Elmham, St Cross South Elmham, All Saints South Elmham, Ilketshall St Andrew, Ilketshall St Lawrence, Ilketshall St Margaret, Ilketshall St John and All Saints Mettingham. The area is bisected in its eastern fringe by the Bungay—Halesworth road that follows the course of Stone Street, a die-straight Roman construction, one of several that can still be traced on any road map of East Anglia. On the whole though the roads around here are anything but Roman in character: narrow, twisting, often bewilderingly changing direction, and marked with confusing signs (too many saints!), it is a good place to visit should you wish to humiliate your Sat Nav. John Seymour in The Companion Guide to East Anglia (1968) describes The Saints as ‘a hillbilly land into which nobody penetrates unless he has good business,’ which is perhaps hyperbolic but there is undoubtedly a feel of liminality to the area that persists to this day.

The Saints is a small, loosely defined area of northeast Suffolk just south of the River Waveney and the Norfolk border. Effectively it is a fairly unremarkable patch of arable countryside that contains within it a baker’s dozen of small villages with names that begin or end with the name of the parish saint: St Peter South Elmham, St Michael South Elmham, St Nicholas South Elmham, St James South Elmham, St Margaret South Elmham, St Mary South Elmham, St Cross South Elmham, All Saints South Elmham, Ilketshall St Andrew, Ilketshall St Lawrence, Ilketshall St Margaret, Ilketshall St John and All Saints Mettingham. The area is bisected in its eastern fringe by the Bungay—Halesworth road that follows the course of Stone Street, a die-straight Roman construction, one of several that can still be traced on any road map of East Anglia. On the whole though the roads around here are anything but Roman in character: narrow, twisting, often bewilderingly changing direction, and marked with confusing signs (too many saints!), it is a good place to visit should you wish to humiliate your Sat Nav. John Seymour in The Companion Guide to East Anglia (1968) describes The Saints as ‘a hillbilly land into which nobody penetrates unless he has good business,’ which is perhaps hyperbolic but there is undoubtedly a feel of liminality to the area that persists to this day.  The village names conjure a medieval world where saint-obsessed religion loomed large. Such a tight cluster of settlements suggests a concentration of population where parishes might eventually combine to form a town or city – with 13 villages and the same number of churches (eleven of which are extant), there were more churches here than in all of Cambridge. But The Saints never coalesced to become a medieval city – none of the villages had a port, defensive structure or even significant market to its credit and consequently the area would slowly slip into obscurity as the medieval era played out and other East Anglia towns and cities – Cambridge, Bury St Edmunds, Ipswich and, of course, Norwich – took the baton of influence and power.

The village names conjure a medieval world where saint-obsessed religion loomed large. Such a tight cluster of settlements suggests a concentration of population where parishes might eventually combine to form a town or city – with 13 villages and the same number of churches (eleven of which are extant), there were more churches here than in all of Cambridge. But The Saints never coalesced to become a medieval city – none of the villages had a port, defensive structure or even significant market to its credit and consequently the area would slowly slip into obscurity as the medieval era played out and other East Anglia towns and cities – Cambridge, Bury St Edmunds, Ipswich and, of course, Norwich – took the baton of influence and power.  It was not always so: one of the villages in particular held great significance in its day. The land covered by the South Elmham parishes was once owned by Almar, Bishop of East Anglia and the late Saxon Bishops of Norwich had a summer palace here at St Cross, now South Elmham Hall. The most intriguing of the churches lies within the same parish. It is not in any way complete but a ruin framed by woodland a good half mile from the nearest road. South Elmham Minster, although probably never a minster proper, is veiled in mystery regarding its origins but its appeal owes as much to its half-hidden location as it does to its obscure history. South Elmham may have once been the seat of the second East Anglian bishopric (the first was in Dunwich, the sea-ravaged village on the Suffolk coast), although North Elmham in Norfolk seems a more likely contender. Whatever the ruin’s original function – a private chapel for Herbert de Losinga, Norwich’s first bishop, is another possibility, or it may even be that a second bishopric was founded here – the church in the wood just south of South Elmham Hall dates back at least to the 11th century. It is probably older in origin – a ninth-century gravestone has been unearthed in its foundations. The site itself is undoubtedly of greater antiquity: a continuation of an earlier Anglo-Saxon presence that occupied the same moated site, which, earlier still, was home to a Roman temple and perhaps, even earlier, a pagan holy place.

It was not always so: one of the villages in particular held great significance in its day. The land covered by the South Elmham parishes was once owned by Almar, Bishop of East Anglia and the late Saxon Bishops of Norwich had a summer palace here at St Cross, now South Elmham Hall. The most intriguing of the churches lies within the same parish. It is not in any way complete but a ruin framed by woodland a good half mile from the nearest road. South Elmham Minster, although probably never a minster proper, is veiled in mystery regarding its origins but its appeal owes as much to its half-hidden location as it does to its obscure history. South Elmham may have once been the seat of the second East Anglian bishopric (the first was in Dunwich, the sea-ravaged village on the Suffolk coast), although North Elmham in Norfolk seems a more likely contender. Whatever the ruin’s original function – a private chapel for Herbert de Losinga, Norwich’s first bishop, is another possibility, or it may even be that a second bishopric was founded here – the church in the wood just south of South Elmham Hall dates back at least to the 11th century. It is probably older in origin – a ninth-century gravestone has been unearthed in its foundations. The site itself is undoubtedly of greater antiquity: a continuation of an earlier Anglo-Saxon presence that occupied the same moated site, which, earlier still, was home to a Roman temple and perhaps, even earlier, a pagan holy place.  We leave the car in a muddy parking area alongside another vehicle and a dumped piece of agricultural machinery. Nearby stands a weather-beaten trestle table that suggests that this once might have served as a designated picnic spot. Now half-submerged in grass and thistles, the table did not look as if any sandwich boxes had been opened on it for some time. Things have changed here a little in recent years: the permissive footpaths that once threaded through the South Elmham estate are no longer available for the public, and the hall itself has been re-purposed for use as a wedding and conference venue. At least the minster was still accessible by means of a green lane and a public footpath across fields.

We leave the car in a muddy parking area alongside another vehicle and a dumped piece of agricultural machinery. Nearby stands a weather-beaten trestle table that suggests that this once might have served as a designated picnic spot. Now half-submerged in grass and thistles, the table did not look as if any sandwich boxes had been opened on it for some time. Things have changed here a little in recent years: the permissive footpaths that once threaded through the South Elmham estate are no longer available for the public, and the hall itself has been re-purposed for use as a wedding and conference venue. At least the minster was still accessible by means of a green lane and a public footpath across fields.  The green lane is flanked by mature hedges frothed white with blackthorn blossom. Reaching its bottom end we turn left to follow a footpath alongside a stream, a minor tributary of the River Waveney; strange hollowed-out hornbeams measure out its bank. Soon we come to the copse that contains the ruin, a rusty gate gives admission across a partial moat and raised bank into what can only be described as a woodland glade. The ancient flint walls of the church stand central, striated by the shadow of hornbeams still leafless in late March. There is no sign of a roof but the weathered walls of the nave are clear in outline, as is the single entrance to the west. On the ground, last year’s fallen leaves provide a soft bronze carpet that is mostly devoid of ground plants.

The green lane is flanked by mature hedges frothed white with blackthorn blossom. Reaching its bottom end we turn left to follow a footpath alongside a stream, a minor tributary of the River Waveney; strange hollowed-out hornbeams measure out its bank. Soon we come to the copse that contains the ruin, a rusty gate gives admission across a partial moat and raised bank into what can only be described as a woodland glade. The ancient flint walls of the church stand central, striated by the shadow of hornbeams still leafless in late March. There is no sign of a roof but the weathered walls of the nave are clear in outline, as is the single entrance to the west. On the ground, last year’s fallen leaves provide a soft bronze carpet that is mostly devoid of ground plants.  Church or not, there is a timelessness to this place in the woods. And a strong sense of genius loci, the sort of thing that put the wind up the Romans with their straight lines and four-square militaristic outlook. I wander off to explore the bank to the west and discover the opening of a badger sett that looks to be newly excavated. Without much expectation, I rummage though the spoil musing that there might just be the remotest of chances that, burrowing deep beneath the mound, the animals have thrown up some treasure long buried in the soil below: an Anglo-Saxon torc, a Roman coin perhaps? I would even settle for a rusty button, but nothing. No matter, the mystery of the place is enough for now. We leave the bosky comfort of the site and retrace our steps along the beck and green lane back to the car. The other car has gone – we never did see its occupants.

Church or not, there is a timelessness to this place in the woods. And a strong sense of genius loci, the sort of thing that put the wind up the Romans with their straight lines and four-square militaristic outlook. I wander off to explore the bank to the west and discover the opening of a badger sett that looks to be newly excavated. Without much expectation, I rummage though the spoil musing that there might just be the remotest of chances that, burrowing deep beneath the mound, the animals have thrown up some treasure long buried in the soil below: an Anglo-Saxon torc, a Roman coin perhaps? I would even settle for a rusty button, but nothing. No matter, the mystery of the place is enough for now. We leave the bosky comfort of the site and retrace our steps along the beck and green lane back to the car. The other car has gone – we never did see its occupants.

I set out from Kessingland, just south of Lowestoft, where a large expanse of dunes and shingle separates the sea from the holiday homes and caravans that line the low clifftop like racing cars at a starting grid preparing to rush towards the sea. Truth be told, there is little in the way to stop them. It may be August but even now the beach is relatively quiet – just a few families and dog-walkers clambering over the dunes to reach the sea, which today is grey, grumpy and not particularly welcoming. The Kessingland littoral is distinguished by its specialist salt-tolerant flora: sea holly, sea pea, sea campion, sea beet – in fact, place a ‘sea’ in front of any common plant name and there is a good chance that such a species will exist and flourish here. Also rooted into the shingle, thriving on little more than sunshine and salt spray, are clumps of yellow-horned poppies with long twisting seed pods. The poppies are mostly past their flowering peak but elsewhere, where there is a thin veneer of soil to root into, colour is provided by stands of rosebay willow herb – a rich purple layer of distraction between the straw-hued shingle and the cloud-heavy sky, both washed of colour in the flat coastal light.

I set out from Kessingland, just south of Lowestoft, where a large expanse of dunes and shingle separates the sea from the holiday homes and caravans that line the low clifftop like racing cars at a starting grid preparing to rush towards the sea. Truth be told, there is little in the way to stop them. It may be August but even now the beach is relatively quiet – just a few families and dog-walkers clambering over the dunes to reach the sea, which today is grey, grumpy and not particularly welcoming. The Kessingland littoral is distinguished by its specialist salt-tolerant flora: sea holly, sea pea, sea campion, sea beet – in fact, place a ‘sea’ in front of any common plant name and there is a good chance that such a species will exist and flourish here. Also rooted into the shingle, thriving on little more than sunshine and salt spray, are clumps of yellow-horned poppies with long twisting seed pods. The poppies are mostly past their flowering peak but elsewhere, where there is a thin veneer of soil to root into, colour is provided by stands of rosebay willow herb – a rich purple layer of distraction between the straw-hued shingle and the cloud-heavy sky, both washed of colour in the flat coastal light.  Further south, the cliffs grow a little higher. Ferrous red and as soft and powdery as halva, they are irredeemably at the mercy of the North Sea tide. And it shows: the cliffs are raw and freshly cleaved, with collapsed chunks that have been further eroded by the incoming tide such that they appear to seep from the cliff bases like congealed gravy. Man-made objects receive no preferential treatment – a collapsed WWII concrete defence bunker slopes between cliff and sand at one point, its long process of total disintegration still in its infancy as its perches ignominiously at 45 degrees, an involuntary buttress for the flaking cliffs.

Further south, the cliffs grow a little higher. Ferrous red and as soft and powdery as halva, they are irredeemably at the mercy of the North Sea tide. And it shows: the cliffs are raw and freshly cleaved, with collapsed chunks that have been further eroded by the incoming tide such that they appear to seep from the cliff bases like congealed gravy. Man-made objects receive no preferential treatment – a collapsed WWII concrete defence bunker slopes between cliff and sand at one point, its long process of total disintegration still in its infancy as its perches ignominiously at 45 degrees, an involuntary buttress for the flaking cliffs.