A pinch of the River Clyde; a squeezing of the water that flows west through Glasgow towards the sea; a watery place where shipyards once dominated the shoreline and the air shook with the hammering of rivets, the scrape and spark of steel plate, the blinding blue light of arc welding. Across the river, south of the here, lies the city district of Govan, depleted of industry now but once the hub for shipbuilding in the region. Here on the northern bank, at Glasgow Harbour on the site of a former shipyard on the edge of Partick, we stand outside the city’s Riverside Museum. The museum is an arresting zinc and glass structure with a steeply curving roofline that resembles a cardiogram – a late work by the Anglo-Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid.

Afloat in the water in front of the museum, in purposeful contrast, is the handsome three-masted sailing ship Glenlee, a trading ship that after circumnavigating the world four times (and rounding Cape Horn 15 times) ended her nautical life as Galatea, a training vessel for the Spanish Navy. Abandoned and forgotten in Seville the ship was eventually saved by a British naval architect and in 1993 was towed home to Glasgow to end her days on the river of her birth. From the deck of Glenlee we can make out the old buildings of Govan across the water. But there is no way to cross, not outside the summer months anyway, as the seasonal ferry has stopped operating. So it means a retreat on foot back to Partick Subway station to take the Inner Circle beneath the river to reach our goal on the other side.

Emerging from the subway into the bright sunlight of a gleaming autumn day, the Govan streets seems quiet, provincial even; not quite what we had been expecting. The Victorian buildings have a patina of age but are well-scrubbed, made of sandstone the colour of ginger cake. Govan’s Old Parish Church is built of the same stone.

Govan is the oldest part of Glasgow. Until 1912 it was a separate burgh that was historically part of Lanarkshire. Once a centre for the ancient Kingdom of Strathclyde or Alt Clut, it was the northernmost part of the Cumbric (a variant of Brythonic or Old Welsh)-speaking region of Hen Ogledd* or the Old North. A monastery was founded here in the 7th-century by King Constantine (later to be canonised as St Constantine of Strathclyde and Govan), to whom the Old Govan Parish Church is dedicated. In the early medieval period Govan was ruled from Dumbarton Rock at the mouth of the Clyde on the opposite shore until it was destroyed by Vikings in 870AD. The Kingdom of Strathclyde, the only part of the Old North not to be conquered by Anglo-Saxons, eventually became part of the Kingdom of Scotland in the 11th century.

Govan Old Parish Church is home to the Govan Stones, a remarkable collection of 31 grave markers that date back to the 9th century. The church, a fine Scottish Gothic Revival building, is not so old but it stands on a sacred site that was in existence long before the Normans came to dominate the lands to the south. Our timing is impeccable – October 31, the Celtic festival of Samhain – is the last day of the year on which the church is open. As our enthusiastic Scottish-Canadian guide explains, it is too expensive to keep the church heated for the winter months and so it is locked up for the duration.

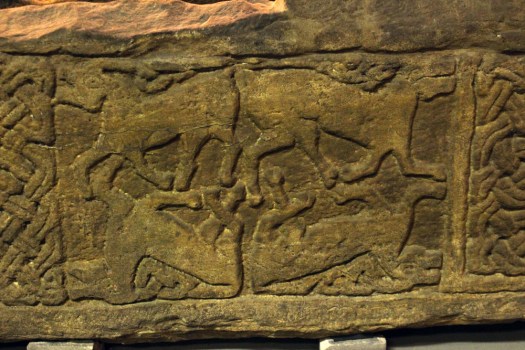

The stones are arranged around the church interior so as to make a circuit. There is intricate Celtic lattice work on the first two – the ‘Sun Stone’ and the Jordanhill Cross – and on the third, the ‘Cuddy Stane’, a representation of a man on a horse, or possibly a donkey (‘cuddy’) bearing a Christ figure. A group of five Viking hogbacks, dark and heavy, and resembling those giant slugs that sometimes venture out along garden paths after rain, dominate the transept. Unnoticed until is pointed out to us, the paws of a supine bear clutch one of the stones at its corners, a complex symbol that combines animal strength and tenderness and might, perhaps, relate to the high-ranking Viking it commemorates. The highlight of the collection is probably the Govan Sarcophagus, the only one of its kind from the pre-Norman era, which was unearthed in the graveyard in 1855. This intricately carved structure is thought to have once held the remains of King Constantine himself, although its symbols suggest that is more likely to have been made a couple of centuries after his death. Elsewhere are ancient stones that have been recycled as markers for later graves – palimpsests where earlier detail has been erased to allow a new name to be cut into the stone.

The stones are arranged around the church interior so as to make a circuit. There is intricate Celtic lattice work on the first two – the ‘Sun Stone’ and the Jordanhill Cross – and on the third, the ‘Cuddy Stane’, a representation of a man on a horse, or possibly a donkey (‘cuddy’) bearing a Christ figure. A group of five Viking hogbacks, dark and heavy, and resembling those giant slugs that sometimes venture out along garden paths after rain, dominate the transept. Unnoticed until is pointed out to us, the paws of a supine bear clutch one of the stones at its corners, a complex symbol that combines animal strength and tenderness and might, perhaps, relate to the high-ranking Viking it commemorates. The highlight of the collection is probably the Govan Sarcophagus, the only one of its kind from the pre-Norman era, which was unearthed in the graveyard in 1855. This intricately carved structure is thought to have once held the remains of King Constantine himself, although its symbols suggest that is more likely to have been made a couple of centuries after his death. Elsewhere are ancient stones that have been recycled as markers for later graves – palimpsests where earlier detail has been erased to allow a new name to be cut into the stone.

The stone for each of the grave markers, like the church itself, comes from the hills across the Clyde. The feat of moving such a heft of stone might seem Herculean in its endeavour but a millennium ago the river would have been shallower and narrower and there would have been a ford across it; there may even have been stepping stones bridging the two shores. Later, in the medieval period, a ferry would have run between the two banks to transport Highland cattle drovers and their stock across the river to markets south of Glasgow.

By the 19th century Govan became better known as a centre for shipbuilding. It would go on to achieve fame as the birthplace of strong-willed characters like Jimmy Reed, Sir Alex Ferguson and Kenny Dalglish. But long before any ship was launched, Govan was a strategic and spiritual centre where Britonnic, Celtic and Scandinavian worlds overlapped thanks to an important crossing place on the river. If the Govan Stones could speak of those who carved them they would, of course, tell you this… in Cumbric naturally.

*Hen Ogledd is also the name of an excellent Newcastle-based musical combo whose work sometimes references the early medieval Brythonic world their name suggests

Just three main roads radiate out of Stornoway, the capital of the Isle of Lewis. One heads across mountains towards Tarbet and Harris to the south; another goes east past the island’s airport and along the Eye Peninsula to come to halt at the lighthouse at Tiumpan Head, while a third leads across the island’s moorland interior to reach its west coast. A little way along this last road is the turn-off to Tolsta, a minor road with the most unexpected of endings. The road passes bungalow settlements and sea-facing graveyards as it leads north. In Hebridean terms, this is relatively densely populated terrain — one settlement merging into the next in a loose sprawl known collectively as Back. This stretch of Stornoway’s hinterland might elsewhere be termed green belt were it not a fact that pretty well anywhere on Lewis and Harris could be described as ‘green’.

Just three main roads radiate out of Stornoway, the capital of the Isle of Lewis. One heads across mountains towards Tarbet and Harris to the south; another goes east past the island’s airport and along the Eye Peninsula to come to halt at the lighthouse at Tiumpan Head, while a third leads across the island’s moorland interior to reach its west coast. A little way along this last road is the turn-off to Tolsta, a minor road with the most unexpected of endings. The road passes bungalow settlements and sea-facing graveyards as it leads north. In Hebridean terms, this is relatively densely populated terrain — one settlement merging into the next in a loose sprawl known collectively as Back. This stretch of Stornoway’s hinterland might elsewhere be termed green belt were it not a fact that pretty well anywhere on Lewis and Harris could be described as ‘green’.

Eleven miles east of the main road, six from the nearest shop (closed on the Sabbath), two miles from the open sea as the raven flies. Glen Gravir – a slender thread of houses stretching up a glen, just four more unoccupied dwellings beyond ours before the road abruptly terminates at a fence, nothing but rough wet grazing, soggy peat and unseen lochans beyond. This was our home for the week, a holiday rental in the Park (South Lochs) district of the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides.

Eleven miles east of the main road, six from the nearest shop (closed on the Sabbath), two miles from the open sea as the raven flies. Glen Gravir – a slender thread of houses stretching up a glen, just four more unoccupied dwellings beyond ours before the road abruptly terminates at a fence, nothing but rough wet grazing, soggy peat and unseen lochans beyond. This was our home for the week, a holiday rental in the Park (South Lochs) district of the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. Gravir, of which Glen Gravir is but an outpost, is large enough to feature on the map, albeit in its Gaelic form, Grabhair. The village – more a loose straggle of houses and plots – possesses a school, a fire station and a church but no shop. A road from the junction with Glenside next to the church winds its way unhurriedly downhill to the sea inlet of Loch Odhairn where there is a small jetty for boats. Some of the houses are clearly empty; others occupied by crofters and incomers, their occupants largely unseen. Others are long ruined, tenanted only by raven and opportunist rowan trees, with roofs absent and little more than chimney stacks and gable walls surviving. It is only a matter of time before the stones that have been laid to construct the walls will be indistinguishable from the native gneiss that underlies the island, surfacing above the bog here and there in outcrops like human-raised cairns. Lewisian gneiss is the oldest rock in Britain. Three billion years old, two-thirds the age of our planet, it is as hard as…well, gneiss. It is the same tough unyielding rock that five thousand years ago was painstakingly worked and positioned at the Callanish stone circle close to Lewis’s western shore; the same rock used to build the island’s churches, which occupy the same sacred sites, the same fixed points of genii loci that had been identified long before Presbyterianism or any another monotheistic faith arrived in these isolated north-western isles.

Gravir, of which Glen Gravir is but an outpost, is large enough to feature on the map, albeit in its Gaelic form, Grabhair. The village – more a loose straggle of houses and plots – possesses a school, a fire station and a church but no shop. A road from the junction with Glenside next to the church winds its way unhurriedly downhill to the sea inlet of Loch Odhairn where there is a small jetty for boats. Some of the houses are clearly empty; others occupied by crofters and incomers, their occupants largely unseen. Others are long ruined, tenanted only by raven and opportunist rowan trees, with roofs absent and little more than chimney stacks and gable walls surviving. It is only a matter of time before the stones that have been laid to construct the walls will be indistinguishable from the native gneiss that underlies the island, surfacing above the bog here and there in outcrops like human-raised cairns. Lewisian gneiss is the oldest rock in Britain. Three billion years old, two-thirds the age of our planet, it is as hard as…well, gneiss. It is the same tough unyielding rock that five thousand years ago was painstakingly worked and positioned at the Callanish stone circle close to Lewis’s western shore; the same rock used to build the island’s churches, which occupy the same sacred sites, the same fixed points of genii loci that had been identified long before Presbyterianism or any another monotheistic faith arrived in these isolated north-western isles. Ancient hard rock (as in metamorphic) may underlie Lewis, but religion is another bedrock of the island. Despite a respectable number of dwellings the only people we ever really see in the village are those who come in number on Sunday. The Hebridean Wee Free tradition guarantees a full car park on the Sabbath when smartly and soberly dressed folk from the wider locality congregate at Grabhair’s church, which, grave, grey and impressively large, is the only place of worship in this eastern part of the South Lochs district.

Ancient hard rock (as in metamorphic) may underlie Lewis, but religion is another bedrock of the island. Despite a respectable number of dwellings the only people we ever really see in the village are those who come in number on Sunday. The Hebridean Wee Free tradition guarantees a full car park on the Sabbath when smartly and soberly dressed folk from the wider locality congregate at Grabhair’s church, which, grave, grey and impressively large, is the only place of worship in this eastern part of the South Lochs district.

At the bottom of the lane beneath the hillside graveyard next to the church are a couple of recycling containers for villagers to deposit their empties and waste paper. Larger items of material consumption are left to their own devices. Rain, wind and thin acidic soil are the natural agents of decay here. Beside the roadside further up from our house lie four long-abandoned vehicles in various stages of decomposition. Engines are laid bare; bodywork and chassis, buckled and distressed, rust-coated in mimicry of the colour of lichen and autumn-faded heather. Cushions of moss have colonised the seating fabric. The rubber tyres remain surprisingly intact, the longest survivor of abandonment. Sharp-edged sedges have grown around the rotting car-carcasses as if to hide them from prying eyes, preserving some modicum of dignity as the wrecks decay into the roadside bog, all glamour expunged from a lifetime spent negotiating the island’s narrow single track roads. On Lewis, vehicles die of natural causes, not geriatric intervention.

At the bottom of the lane beneath the hillside graveyard next to the church are a couple of recycling containers for villagers to deposit their empties and waste paper. Larger items of material consumption are left to their own devices. Rain, wind and thin acidic soil are the natural agents of decay here. Beside the roadside further up from our house lie four long-abandoned vehicles in various stages of decomposition. Engines are laid bare; bodywork and chassis, buckled and distressed, rust-coated in mimicry of the colour of lichen and autumn-faded heather. Cushions of moss have colonised the seating fabric. The rubber tyres remain surprisingly intact, the longest survivor of abandonment. Sharp-edged sedges have grown around the rotting car-carcasses as if to hide them from prying eyes, preserving some modicum of dignity as the wrecks decay into the roadside bog, all glamour expunged from a lifetime spent negotiating the island’s narrow single track roads. On Lewis, vehicles die of natural causes, not geriatric intervention.

Our cottage was rented as an island base: a place to eat, rest and sleep before setting off each morning on a long drive to visit one of Lewis’s far flung corners. Happily, it feels like a home, albeit a temporary one – a domestic cocoon of cosiness with all the modest comforts we require. Its small garden is a haven. As everywhere on the island, tangerine spikes of montbretia arch like welder’s sparks from the grass. Rabbits scamper about on the lawn, colour-flushed parties of goldfinches feed on the seed heads of knapweed outside the kitchen window. Robins, wrens and blackbirds flit around the trees and shrubs that envelop the cottage – non-native plants that have adapted to the harsh weather conditions of this north-western island, softening an outlook that on a grey, wind-blown day, with a gloomy frame of mind, might be considered bleak.

Our cottage was rented as an island base: a place to eat, rest and sleep before setting off each morning on a long drive to visit one of Lewis’s far flung corners. Happily, it feels like a home, albeit a temporary one – a domestic cocoon of cosiness with all the modest comforts we require. Its small garden is a haven. As everywhere on the island, tangerine spikes of montbretia arch like welder’s sparks from the grass. Rabbits scamper about on the lawn, colour-flushed parties of goldfinches feed on the seed heads of knapweed outside the kitchen window. Robins, wrens and blackbirds flit around the trees and shrubs that envelop the cottage – non-native plants that have adapted to the harsh weather conditions of this north-western island, softening an outlook that on a grey, wind-blown day, with a gloomy frame of mind, might be considered bleak. Most days on our jaunts around the island we would see an eagle or two, golden or white-tailed, sometimes both. The majority of these sighting are in more mountainous Harris, or in that southern part of Lewis that lay close to the North Harris Hills, but on our last day on Lewis we see a white-tailed eagle fly over Orinsay, a village relatively close to where we have been staying. An hour later we spot another bird swoop along the sea loch at Cromore, a coastal village that lies a few miles to the north. It might well be the same bird. White-tailed eagles are very large and hard to miss, and their feeding range is enormous. But that is exactly how Lewis seems – enormous, almost unknowable despite its modest geographical area. A place larger than the shape on the map – a mutable landscape of rock, sky and water that does not easily lend itself to the reductionism of two-dimensional cartography.

Most days on our jaunts around the island we would see an eagle or two, golden or white-tailed, sometimes both. The majority of these sighting are in more mountainous Harris, or in that southern part of Lewis that lay close to the North Harris Hills, but on our last day on Lewis we see a white-tailed eagle fly over Orinsay, a village relatively close to where we have been staying. An hour later we spot another bird swoop along the sea loch at Cromore, a coastal village that lies a few miles to the north. It might well be the same bird. White-tailed eagles are very large and hard to miss, and their feeding range is enormous. But that is exactly how Lewis seems – enormous, almost unknowable despite its modest geographical area. A place larger than the shape on the map – a mutable landscape of rock, sky and water that does not easily lend itself to the reductionism of two-dimensional cartography.