Two weeks ago I read a news article about the demolition of the cooling towers at Ironbridge on the River Severn in Shropshire. Their final demise was witnessed by many who came to see the four great towers collapsing after a controlled detonation. The towers had stood for exactly half a century. Opened in 1969, the power station they belonged to had stopped generating electricity in November 2015. At one time it had provided enough electricity to power the equivalent of 750,000 homes. The space that will be made available by their removal should be sufficient for around 1,000 new homes, a park and ride, a school and leisure facilities.

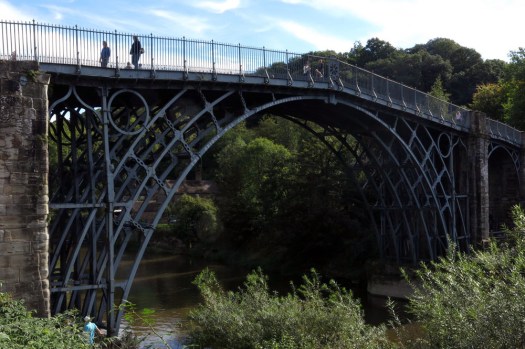

Before they came down the towers received a musical farewell when Zoë Beyers from the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire performed a solo violin piece on one of the tower platforms. The music was elegaic, an echo of the mournfulness felt by local residents and former power station workers for whom the towers had been a large part of their life. Reduced in seconds to a mere imprint of memory, the Ironbridge geography was instantly transformed for those who lived there. Particularly poignant was the fact that a little way downriver was the original Iron Bridge built in 1781, the first major bridge of its kind in the world. It was no stretch of truth to infer that it was here in Shropshire at Ironbridge and nearby Coalbrookdale that the Industrial Revolution really began.

In my, admittedly limited, experience cooling towers have always stood for something. They were markers on the landscape that held deeper meaning than just supersized industrial chimneys. Travelling north up the A1(M), the cluster of eight towers at Ferrybridge in West Yorkshire always seemed to mark an arrival in the North far more effectively than any roadside sign could. Their presence spoke of a cultural transition as much as a geographical one, a shift of emphasis from pastoral to industrial. But these too were earmarked for destruction, and in 2019 five of the towers were demolished. The remaining three will be removed by summer 2021. Similarly, the pair of cooling towers that used to stand outside Sheffield at Tinsley overlooking the M1 motorway always seemed like an omphalos for Don Valley industry – a centre of gravity for the steel, coal, fire and dirt of South Yorkshire. These were of particular significance for me as they were visible from the classroom where, in a previous life, I had my first practical experience as a geography teacher. These twin towers – the ‘salt and pepper pots’ as they were sometimes known – had been redundant since the 1970s, although they managed to remain standing until 2008. Despite a scheme to convert them into giant works of public art they could not be saved. Now they are gone, redacted from the landscape, as are the steel foundries of Sheffield’s Brightside – the industrial endeavour of generations of Sheffield lives reduced to little more than memory and a plaque at a shopping mall

I do not wish to romanticise coal-fired power production – it is undeniably dirty, polluting and a significant contributor to climate change – but I cannot help but find some of the fabric of its production strangely beautiful. Smoke-belching cooling towers may well be the embodiment of Blake’s dark satanic mills but, once abandoned, the heft of their curving brickwork seems to take on an eerie beauty. Silent witnesses of the recent industrial past, their inhuman scale and brooding presence make them emblematic of the hubris that persists in these uncertain times.