To begin the New Year, here is a piece on something close to home and close to heart – allotments. I touched on this subject briefly last year in my post on Dacha.

The feature below originally appeared in Issue 3 of the very excellent EarthLines magazine last November. The issue content for the forthcoming February edition can be seen here.

Scratching the Earth: a celebration of the English allotment

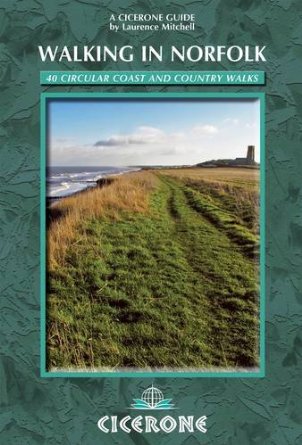

Words and images by Laurence Mitchell

I am a scratcher, a scraper of earth. Not a full-time farmer but a fair-weather organic vegetable grower. ‘Urban smallholder’ might be a better description, but what I hold is very small indeed and, despite the regular print of my boots, I do not have possession of my own patch of dirt. What I have is something altogether different: temporary stewardship of that quintessentially English tract of land, a city allotment plot.

Scotland also has them but, like beech trees, they tend to be thin on the ground north of the border. But travelling by train across England or Wales you cannot miss them, especially as you make the final backyard run into towns and cities: a few acres of long thin plots with ragged lines of vegetables, tumble-down sheds, compost heaps and algae-stained green houses. In winter, there will probably be stands of frosted Brussels Sprouts (contrarily, the most singularly English of vegetables, which you would be hard-pressed to find in the Belgian capital); in summer, you will inevitably see vines of runner beans entwined up wigwam frames of bamboo, scarlet flowers scrambling for the sky. From your window seat you might witness solitary figures hunched over tending the soil, or red-faced individuals dressed in old clothes clutching a fistful of leaves or a plastic container of soft fruit.

You will not find these oases of fecundity anywhere else in Europe – not quite like this, anyway. True, Germans and Danes have some sort of equivalent with their tidy city gardens, but these have the well-ordered feel of suburbia about them: neat gingerbread cottages, straight lines, pampered lawns and picket fences. In contrast, there is more than a touch of anarchy about the English counterpart: an improvised, hotchpotch character that comes partly from the inherited hubris of surviving maritime blockades and aerial attack, along with the earthy pragmatism of having to live on wits and scraps during wartime. But they have a role to play in times of plenty too; allotments serve as places of refuge for those fleeing latter-day consumer culture. With garden sheds cobbled together from builder’s waste and unhinged old doors, allotments resemble nothing less than Third-World shanty towns – squatter settlements, bidonvilles or favelas. That is, of course, minus the misery: there are no drugs, guns or mudslides to torment their part-time occupants. The worst that can happen here is a plague of aphids, potato blight or tools stolen from sheds.

There is a freedom that comes with all this, this make-do and mend, this non-reliance on throwing money at anything; this quiet undemonstrative snub of consumerism. These are not private gardens after all, where such messy improvisations might snobbishly be seen as a decay of civic pride – the abandoned fridge reverting to nature on the untended scrap of lawn. Rather, they are communal spaces where the individual can do much as he or she wishes. This is not to say that there are no rules of engagement – there are – but these tend to be unwritten yet universally understood by anyone who have served enough time on a plot. Newcomers who fritter away good money on smart sheds and new tools are viewed with suspicion and are seen as unlikely to stay the course – this is usually the reality. Neophyte allotment holders are often viewed as fly-by-night lightweights. To be accepted and, harder still, to be taken seriously, it is necessary to earn one’s spurs, to prove oneself worthy of the respect of the old hands. A decade or so will probably do it, although not necessarily. As well as a place where old-fashioned neighbourliness and community spirit can shine, this is also the sort of territory where traditional English bloody-mindedness can also be freely and wilfully expressed.

Lengthy tomes have been written concerning the history of the English allotment. Suffice it to say, they mostly came into being during one of the nation’s more enlightened interludes when the paternalistic powers-that-be saw fit to grant plots of unused urban space for the use of the city-dwelling working class. The urban allotment was devised as a place where the poor could grow fruit, flowers and vegetables, take health-giving exercise and practice the sort of rosy-cheeked temperance beloved by Victorian philanthropists who, well-meaning though they might have been, felt it necessary to offer a firm guiding hand to the lower orders lest they fall prey to temptation and collapse helplessly in an orgy of gin, laudanum and sexual vice.

Ironically, many of the workers that swelled Britain’s new industrial cities in the Victorian period came because they had already been disenfranchised from the soil they had been sweating over for generations. The Enclosure Movements of the late 18th and early 19th centuries meant that many country dwellers had ended up as landless labourers, subject to the whims and requirements of the landowning class. It was only a savage depletion of their number as cannon fodder during World War I that led to agricultural labourers becoming a scarce-enough commodity for their value to be begrudgingly appreciated once more. Nevertheless, farming declined through the first half of the 20th century, and when it did finally recover after World War II it was with the assistance of power machinery not horny-handed men with teams of horses.

Working men had already taken a stand some centuries earlier. At the outbreak of the English Civil War, the Diggers, led by Gerrard Winstanley, were Christian nonconformists who wished to reform the existing social order with the introduction of egalitarian rural communities. True to their name, they dug; cultivating common land with the claim that the people had been robbed of their birthright by the ruling class that had become established six centuries earlier around the time of the Norman Conquest. The Diggers would fail in their quest, of course, as would their contemporaries, the Levellers – so-named because of their early tendency to raise hedges in rural enclosure riots. What has persisted, though, is Winstanley’s belief that ‘true freedom lies where a man receives his nourishment and preservation, and that is in the use of the earth’ and the notion of ‘the Earth’ (note the capital this time) ‘as a Common Treasury for all’. Effectively, the provision of allotments would represent a form of benign tokenism: the equivalent of scraps from the kitchen for the poor, a handful of coins from the Common Treasury that only a small élite held the keys to.

The earliest allotments were founded in rural areas during the reign of Elizabeth I when the first enclosures of the commons were partly compensated by allocations of land to tenant cottages. The General Enclosure Act of 1845, anticipating civil unrest as a result of earlier sweeping enclosure legislation, made provision for landless poor in the shape of so-called ‘field gardens’ of a quarter of an acre, but only a tiny fraction of land was effectively provided from the enclosed territory. A later act of 1887 obliged local authorities to provide allotments if there was sufficient demand, and this was strengthened by a follow-up act of 1908 that imposed more binding responsibilities.

Allotments came into their own in times of hardship. During World War I, the food blockade imposed by the Germans resulted in greater demand for allotments. In the Great Depression of the 1930s, unemployed coal miners in Wales and northeast England would somehow manage to feed large families on potatoes, cabbages and leeks grown on exhausted soot-begrimed plots. Later, during World War II, food blockades and a lack of farm workers meant that allotments would be the only source of fresh greens for many poorer city dwellers. ‘Dig for Victory’ became the watchword, although food rationing, which continued until 1954, was an equally strong imperative. Following the Allied victory in 1945, allotment numbers declined dramatically right up until the 1970s, when an upsurge of interest in self-sufficiency caused a blip in the overall trend. Since the 1990s the decline has been relatively slow, despite enormous pressure to sell off prime urban sites for building land.

The most controversial allotment story in recent years concerns the fate of the Manor Gardens allotments in East London. These allotments, once a green refuge of tomatoes and turnip, carrot and coriander next to the River Lea, were cleared in 2007 to make way for landscaping for the London 2012 Olympics. They were fêted in the British media, and painted and photographed by inner city archivists. It does not take much imagination to understand the sense of loss felt by a poor inner-city community for which allotments such as these had long provided a vital social space. Serving as a combined place in the country, picnic spot and community centre for its multi-cultural tenants, it is hard to envisage a better tribute to social cohesion, cultural and class integration and eco-cuddliness. ‘It was an island surrounded by water. Lea Valley Park made a nature reserve at the back of it. You walked out of lousy old Hackney… into Shangri La,’ as one former allotment holder confessed who had inherited his plot from his father back in 1948. Several former tenants have even had their ashes scattered quietly here – a sacred site in the hidden urban core desecrated in the name of progress and ‘urban renewal’, air-brushed and landscaped as part of the warp and weft of the 21st century ‘Olympic’ capital. Since the allotments were cleared, and a temporary alternative site offered, an agreement has been made to reinstate them on the original site once the Games are over. Unfortunately, Marsh Lane, the makeshift new site to which the plots have been temporarily relocated, has, as its name suggests, very poor drainage.

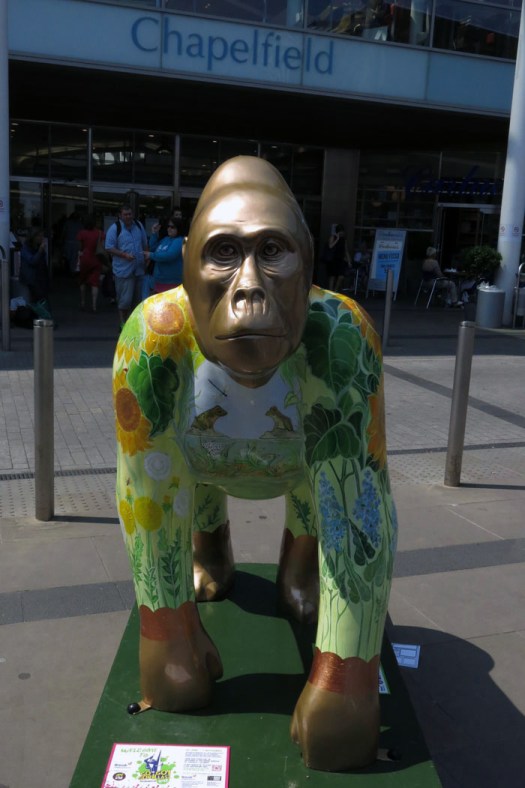

My own humble plot in Norwich took an age to acquire. I placed my name on a waiting list and bided my time for several years before an unexpected telephone call one wintry morning offered me an allotment a couple of miles from my home. I was required to act quickly, as the city council needed a decision that same day. It was hardly perfect – a large rectangle of coarse grass fringed on one side by a long-neglected plot buried in head-high bramble thorns. The plot was close to the edge of the allotments, near to a boundary fence that had been breached by residents of the surrounding council estate, who had chosen the plot next door as a convenient spot to deposit their unwanted household rubbish – shattered television tubes and dismembered bicycles, broken glass and metal detritus. Naturally, I said ‘yes’ immediately, excited that finally I had my own scrap of land to do with as I wished. It may have been in the blood: my grandfather had worked as a gardener and his immediate Victorian ancestors were among those who had exchanged tilling the land and work ‘in service’ to the gentry for more profitable but soul-destroying work in the mills and factories of the English West Midlands. Undoubtedly, there was something primordial in my craving: an atavistic urge to work the earth and practice the alchemy of producing food from dirt, sweat and a packet of seed.

It is easy to over-romanticise the notion of an oasis of peace in an urban environment. The soundtrack to my labours may sometimes be birdsong – or more often the harsh screech of bad tempered gulls – but above the punctured-tyre hiss of tinnitus I am also privy to the familiar click-track of council estate Britain – slamming car doors, raised voices, domestic arguments. And it is not just the birds who croon: one of my allotment neighbours is an unconscious whistler, though the only tune fragment he seems to know is the chorus from ‘Hole in My Shoe’ by Traffic, a Top Ten hit back in 1967. Why is this so fixed in his brain, as repetitive as birdsong? One day the local starlings will probably also mimic the refrain – either that or ‘Popeye the Sailor Man’, which chimes metallically and repeatedly from a cruising ice-cream van – and which is, fittingly perhaps, a song about spinach.

But an allotment can be genuinely magical on occasion: a direct link with the world of nature that lies all around but is all too easy to overlook and increasingly hard to connect with whilst living in a city – a world more feral than truly wild, perhaps, but a cogent reminder of it nevertheless. Arriving early in the morning, you may be lucky enough to witness a family of neighbourhood foxes basking in the low sun – hardly tame, but not exactly fearful either. These magnificent rusty creatures, although now commonplace in urban Britain, still engender wild associations. Reviled by some for their scavenging habits, loved by others for their feral tenacity, they still manage to quicken the heart of city-dwellers with their untamed animal arrogance. And when the pigeons, who wait lazily in trees for cabbage patches to be left unguarded, scatter instantly in a slack-winged flurry of panic, you know that a sparrowhawk has been spotted on the prowl, keen red eyes and cruel talons ready to swipe at unwatchful prey.

An urban existence tends to hold nature away at arm’s length, a little offended perhaps at its unpredictable character and our frail human inability to control it. With tall buildings blocking the sun, and central heating blurring the change of seasons, a patch of dirt untainted by real estate is enough to remind ourselves of the greater seasonal dramas at work. In January, the ground may be too frozen to work and last season’s parsnips will grip the soil as if they were slaves to gravity. A snatch of early March sunshine can warm the air sufficiently to bring out hibernating butterflies from their allotment shed hideaways: gorgeous glimpses of colour – a fluttering tortoiseshell, an eye-winged Peacock, a raggedy Comma – punctuating the afternoon. In contrast, those Lepidoptera that arrive in abundance later in the year – cabbage whites and leek moths – are viewed with all the affection of barnstorming rats. In the dog days of August, drought and a stiff summer breeze is sometimes all it takes to blow away precious topsoil as we slavishly hoe away the weeds: pale dust that sticks to legs before filtering down to boots. Wet warm weather is worse: no chance to hoe away the fast-growing weeds that thrive so much better than those vegetables we try to nurture. Bindweed, couch grass, thistle, horse-tail – the lexicon of horticultural hate.

As allotment holders, we tend to be finely tuned to the vicissitudes of weather and the long-game of climate fluctuation. Our knowledge and memory of the year just passed is more sophisticated than a simple appraisal of ‘cold winter’ or ‘wet summer’. We know from experience that the mild spring and moist summer last year was excellent for the fruit harvest, as we remember plums and damsons that bent the branches earthwards with the weight of their juicy, skin-bursting load – a veritable jamboree that we are still enjoying preserved in jars. It tends to be feast and famine though, and that same hard-won experience tells us that a poor crop will no doubt ensue this season, the trees exhausted and needing to recoup energy following the ostentatious display of last year’s fruit-fest. Besides, it was a cold wet spring too, and so flowering trees were unable to set fruit.

As allotment holders, we tend to be finely tuned to the vicissitudes of weather and the long-game of climate fluctuation. Our knowledge and memory of the year just passed is more sophisticated than a simple appraisal of ‘cold winter’ or ‘wet summer’. We know from experience that the mild spring and moist summer last year was excellent for the fruit harvest, as we remember plums and damsons that bent the branches earthwards with the weight of their juicy, skin-bursting load – a veritable jamboree that we are still enjoying preserved in jars. It tends to be feast and famine though, and that same hard-won experience tells us that a poor crop will no doubt ensue this season, the trees exhausted and needing to recoup energy following the ostentatious display of last year’s fruit-fest. Besides, it was a cold wet spring too, and so flowering trees were unable to set fruit.

Summer has fluctuations of temperature but the mere yo-yo-ing of a column of mercury discloses little useful information. The weather as reflected in the dynamics of insect populations reveals far more. A consistently warm period heralds an invasion of parthenogenetic sap-suckers: aphids – green, white or black. Warmer still, then expect a sudden boost in the population of aphids’ red-spot nemesis: ladybirds, the nation’s favourite beetle. We know – or rather, learn from old hands – that if the summer is cool and wet then runner beans will probably thrive; a hot dry August, then French beans will do better than their flat-pod British cousins – a bluff Gallic reminder of their continental provenance. Sudden weather changes – cool to hot, wet to dry – and onions will bolt, in a hard-wired urge to flower, set seed and survive genetically for another generation. Winter, too, has subtle degrees of cold that are reflected in the fortunes of the plot. A hard frost that rimes the waxy leaves of cabbages may deter hungry birds, but only to a point. Woodpigeons that generally prefer to shred young broccoli leaves will, in really hard weather, turn the attention of their serrating beaks to the normally unappealing stands of kale if all the more palatable brassicas are efficiently netted. At least we have no rabbits or deer to contend with. Winter is largely a time of fallow and reclamation, but cold weather is no barrier to hardier plot-holders, as there are many ways to warm up, and few activities are more rewarding than turning the soil on a cold misty day observed by a worm-hungry, winter-fluffed robin.

After a while working a plot, subtleties of terrain become apparent and the presence of microclimates reveal themselves. My plot lies at the corner of the block and, with the land sloping gently towards it from both north and west, it is something of a frost pocket. Arrive early enough in the day and it is possible to witness a thin layer of cold air sliding menacingly downhill like dry ice on a stage set, frost-burning tender leaves in its wake. The leaves of early potatoes curl and blacken down here when those higher up near the entrance gate stand green and firm, unaffected by overnight frost. One learns to adapt – plant a little later, earth soil up higher.

Intimacy with the vagaries of the weather is one thing, but as allotment holders we also get to know the topography of the ground beneath our feet with great precision, as years spent hoeing, weeding, digging and harvesting engender a close familiarity with our own designated patch of earth. The small territory that is our plot becomes the place on Earth we know most intimately: a microcosm of achievement, change and intent. We create mental maps of the minutiae of its landscape by repetition, by constant stalking. Without recourse to paper or plan we can map our own territories with quite alarming accuracy. These features appear on no known charts other than those in our mind’s eye. On my own: Couch Grass Hill (a two metre-high man-made round barrow – the clue’s in the name), the asparagus bed, the bramble patch, the soft fruit enclave, the ‘wildlife area’ (former raised beds now rotting under grass and wild flowers), the old pear tree (inherited – purveyor of hard, dry fruit), the apricot tree (planted – purveyor of no fruit thanks to late frosts). As inheritors of a relatively blank canvas we bring the plot into being, unwittingly creating songlines of place and event in the process: the exact location where I once saw a toad, the burrow where foxes used to lived, the place where I once cut myself on hidden glass, where I lost my Swiss Army knife (thus far, a forgotten song). Paths are marked – or rather, left un-dug. Unplanned desire paths are created by repeated footfall – the way through long grass and nettles to the shed where I keep tools (foxes, too, used to leave imprints of regular pathways through the grass before they deserted for pastures new). Each plot is a palimpsest of that which came before, previous tenants leaving marks that fade with time (or grow and mature as in the case of fruit trees). Like a river, the plot is both permanent and ever-changing.

More than anything, stewardship (and that is what it is – the land is owned by faceless others) of an allotment affords a taste of poverty – real life-on-the-edge poverty: an oblique empathy with those millions whose very existence depends on whether their crops succeed or fail. We in the West are, of course, mere dabblers – we will not go hungry – but we become attached nevertheless, and the working of an allotment gives some flavour of deep involvement with the earth and what it must feel like if environmental disaster occurs or ancestral land is stolen or gerrymandered by politics and territorial conflict.

The tenure of an allotment is a sometimes frustrating and occasionally heartbreaking business, but there’s beauty in the organic industry of it all. Leaves, weeds and cuttings rot down in time to make rich black compost. Even old clothes: this is the closest that you can get to giving a worn-out pair of jeans a Tibetan sky burial. Put your trust in bacteria and worms, organise them a little, and in a year or two they will be helping to nurture potatoes and onions. The best thing of all, though, is to see the plants grow before your eyes: the seed that transforms into a tiny plant that, before you know it, morphs into something that actually tastes good. As spring bleeds into summer, bright red bean flowers drop like confetti to reveal miniature pods; asparagus spears push upwards through the soil inviting you to savour their piss-tainting delicacy; yellow squashes swell visibly until they are almost too heavy to lift, and potatoes fatten in trenches hiding their treasure underground until it is no longer possible to resist digging up that first forkful of the season. All life is here: birth, sex and death. Naturally, as many allotment holders are well into their later years it is usually the last of this triumvirate that is foremost in their minds. All the more reason, then, to savour the horticultural equivalent of the first two.

‘The Triangle’ is a local name that was sometimes used to refer to the parishes of Aldeby, Wheatacre and Burgh St Peter in southeast Norfolk. Bound on two sides by a bend of the River Waveney and on the other by the now-dismantled Beccles to Great Yarmouth railway, the triangle of land so defined has something of the feel of an island to it. There is no through road here, just a quiet single-track lane that links the farmsteads on the marshland edge. To the north, east and south a large flat area of marshes lies between the relatively high land of ‘The Triangle’ and the river itself.

‘The Triangle’ is a local name that was sometimes used to refer to the parishes of Aldeby, Wheatacre and Burgh St Peter in southeast Norfolk. Bound on two sides by a bend of the River Waveney and on the other by the now-dismantled Beccles to Great Yarmouth railway, the triangle of land so defined has something of the feel of an island to it. There is no through road here, just a quiet single-track lane that links the farmsteads on the marshland edge. To the north, east and south a large flat area of marshes lies between the relatively high land of ‘The Triangle’ and the river itself. Burgh St Peter’s Church of St Mary the Virgin is one of Norfolk’s oddest churches as its tower is in the form of a five-section ziggurat (or, as some have fancied, a collapsible square telescope). The body of the church dates from the 13th century but the tower is an 18th-century addition, supposedly inspired by the Italian travels of William Boycott, the rector’s son. A dynasty of Boycotts served the church for a continuous period of 135 years and Charles Cunningham Boycott, the son of the second Boycott rector, gave the term ‘boycott’ to the English language when he behaved badly over absentee rents in Ireland and was socially ostracised as a result.

Burgh St Peter’s Church of St Mary the Virgin is one of Norfolk’s oddest churches as its tower is in the form of a five-section ziggurat (or, as some have fancied, a collapsible square telescope). The body of the church dates from the 13th century but the tower is an 18th-century addition, supposedly inspired by the Italian travels of William Boycott, the rector’s son. A dynasty of Boycotts served the church for a continuous period of 135 years and Charles Cunningham Boycott, the son of the second Boycott rector, gave the term ‘boycott’ to the English language when he behaved badly over absentee rents in Ireland and was socially ostracised as a result.

![Hereford_mappa_mundi_14th_cent_repro_IMG_3895[1]](https://eastofelveden.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/hereford_mappa_mundi_14th_cent_repro_img_38951.jpg?w=525)

![U237135ACME[1]](https://eastofelveden.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/u237135acme1.jpg?w=525)