Tucked away in the north Norfolk coastal hinterland, close to the villages of Overstrand and Northrepps, is a group of small ponds known as the Shrieking Pits. More of the same can also be found a few miles further west near Aylmerton close to Felbrigg Hall. Thought to be early medieval excavations for iron ore, the resultant pits have long been filled with water and softened by vegetation to allow them to blend in with the scenery as if they were natural features in this gentle post-glacial landscape.

Seeking them out, we made our way on foot from Overstrand, following the Paston Way inland through dark woodland and prairie-sized fields of barley and oilseed rape. The pits lie amidst arable land just beyond a farm at Hungry Hill, a name that points towards agricultural impoverishment at some time in the past. The pits stand beside a green lane, a byway of some antiquity that may have been here as long as the excavations themselves.

The first one we come across is small, surrounded by willows of a uniform height. In the ring of tree shade that encloses the shallow pond, a wooden palette left over from some undefined farming business lies next to the water liked an abandoned raft. The main ‘pit’ is nearby, an altogether larger and more impressive pond edged in by semi-recumbent oaks. The water is glassy and ink-black, suggesting great depth and perhaps a little menace. On the far bank the surface is coated with pond weed the colour of puréed peas. A small wooden notice board has been placed next to one of the oaks is but it is bare, its writing long gone to leave it devoid of information other than that which can be told by wood grain alone. Despite this unwitting redaction, a tangible sense of genius loci suggests that there is something to be told of this place other than a chance meeting of trees and water.

Naturally with a name like Shrieking Pit there is a strong likelihood of dark legend. The mundane answer is that the name alludes to the sound emitted by the exposed gravels. But does gravel really shriek? It scrapes and it crunches but does it make a noise quite so dreadful? Shriek is a loaded word, a term that evokes emotion – fear, dismay, even terror. It is these qualities that inform the folklore associated with the place.

The story goes that a grieving young woman haunts the locality. It tells of a heartbroken 17 year-old called Esmeralda who was seduced and then abandoned by a duplicitous local farmer. Inconsolable, the desperate young woman is said to have thrown herself into the water of the pit one dark night before immediately regretting her decision and crying for help that did not come. Her unheard cries are said to be heard at the spot each February 24th, the anniversary of her death.

Another story tells of a horse and cart vanishing without trace in the pool’s murky depths. Looking at the black unreflecting water it seems perfectly possible. Places such as this, although mere dust specks on the map, are the bread and butter of rural folklore. Such places inevitably become repositories of legend – features where the landscape can be painted with tales of intrigue, romance and horror. As the notice board is currently blank perhaps we should feel free to write our own story.

References:

http://www.heritage.norfolk.gov.uk/record-details?MNF6787-Shrieking-Pits

If trees could only speak. If they had some semblance of sentience and memory, and a means of communication, what would they tell us? Ancient trees – or at least those we suspect to be very old – are usually described in terms of human history. Perhaps as humans it is hubris that requires us to define them in this way but the fact is that by and large they tend to outlive us: many lofty oaks that stand today were already reaching for the sky when the Industrial Revolution changed the face of the land over two centuries ago. This linkage of history and old trees has resulted in some colourful local history. The story of the future King Charles II hiding from parliamentarian troops up a pollarded oak tree in Boscobel, Shropshire carried sufficient potency for the original tree to have been eventually killed by souvenir hunters excessively lopping of its branches as keepsakes. Undoubtedly the stuff of legend, Royal Oak ended up becoming the third commonest pub name in England. A long-established folk belief also tells of the Glastonbury Thorn, the tree which is said to have grown from the staff of Joseph of Arithmathea whom legend has it once visited Glastonbury with the Holy Grail. What was considered to be the original tree perished during the English Civil War, chopped down and burned by Cromwell’s troops who clearly held a grudge against any tree that came with spiritual associations or historical attitude.

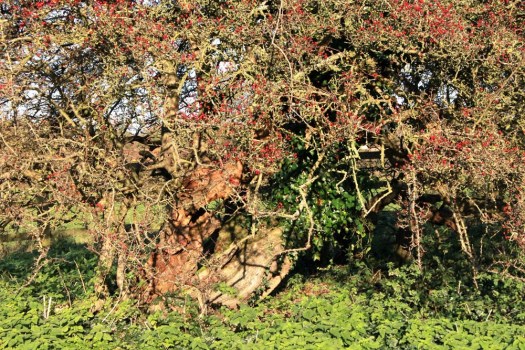

If trees could only speak. If they had some semblance of sentience and memory, and a means of communication, what would they tell us? Ancient trees – or at least those we suspect to be very old – are usually described in terms of human history. Perhaps as humans it is hubris that requires us to define them in this way but the fact is that by and large they tend to outlive us: many lofty oaks that stand today were already reaching for the sky when the Industrial Revolution changed the face of the land over two centuries ago. This linkage of history and old trees has resulted in some colourful local history. The story of the future King Charles II hiding from parliamentarian troops up a pollarded oak tree in Boscobel, Shropshire carried sufficient potency for the original tree to have been eventually killed by souvenir hunters excessively lopping of its branches as keepsakes. Undoubtedly the stuff of legend, Royal Oak ended up becoming the third commonest pub name in England. A long-established folk belief also tells of the Glastonbury Thorn, the tree which is said to have grown from the staff of Joseph of Arithmathea whom legend has it once visited Glastonbury with the Holy Grail. What was considered to be the original tree perished during the English Civil War, chopped down and burned by Cromwell’s troops who clearly held a grudge against any tree that came with spiritual associations or historical attitude. There is an ancient thorn in Norfolk that is sometimes connected with the same Joseph of Arithmathea myth. Hethel Old Thorn can be found along narrow lanes amidst unremarkable farming country 10 miles south of Norwich. Close to the better known

There is an ancient thorn in Norfolk that is sometimes connected with the same Joseph of Arithmathea myth. Hethel Old Thorn can be found along narrow lanes amidst unremarkable farming country 10 miles south of Norwich. Close to the better known  At an estimated 700 years old this is thought to be the oldest specimen of Crataegus monogyna in the UK. Like the nearby Kett’s Oak, the thorn was thought to be a meeting place for the rebels during

At an estimated 700 years old this is thought to be the oldest specimen of Crataegus monogyna in the UK. Like the nearby Kett’s Oak, the thorn was thought to be a meeting place for the rebels during  The far west of Norfolk between Terrington St John and Walsoken on the Cambridgeshire border is often referred to as Fen country but technically it is part of the Norfolk Marshland. John Seymour in his Companion Guide to East Anglia (1970) writes: “The Marshlands are not to be confused with the Fens. The Marshlands, nearer to the sea than the Fens, are of slightly higher land, not so subject to flooding, and have been inhabited from the earliest times”.

The far west of Norfolk between Terrington St John and Walsoken on the Cambridgeshire border is often referred to as Fen country but technically it is part of the Norfolk Marshland. John Seymour in his Companion Guide to East Anglia (1970) writes: “The Marshlands are not to be confused with the Fens. The Marshlands, nearer to the sea than the Fens, are of slightly higher land, not so subject to flooding, and have been inhabited from the earliest times”.  Like the Fens proper this is a region of wide horizons and big skies, a table-flat landscape of barley and mustard fields, of plantations of poplars and lonely farmsteads, of electricity pylons that march across the landscape like robotic sentinels. This is the countryside of

Like the Fens proper this is a region of wide horizons and big skies, a table-flat landscape of barley and mustard fields, of plantations of poplars and lonely farmsteads, of electricity pylons that march across the landscape like robotic sentinels. This is the countryside of  This region, along with the Fens to the west, is a Brexit stronghold where many bear a grudge towards the Eastern Europeans who come to work in the fields here. Antipathy to itinerant farm labourers is nothing new and Emneth, a village located hard against the Cambridgeshire border, has become particularly, and probably unfairly, infamous thanks to its Tony Martin connection. Interestingly, John Seymour, writing in the late 1960s, describes Emneth as having “one of the pubs in the Wisbech fruit-growing district that does not display the racialist (and illegal) sign: NO VAN DWELLERS, and consequently it is one of the pubs in which a good time may often be had”. They still grow fruit in the Wisbech district but I cannot vouch for the welcome currently proffered by its pubs.

This region, along with the Fens to the west, is a Brexit stronghold where many bear a grudge towards the Eastern Europeans who come to work in the fields here. Antipathy to itinerant farm labourers is nothing new and Emneth, a village located hard against the Cambridgeshire border, has become particularly, and probably unfairly, infamous thanks to its Tony Martin connection. Interestingly, John Seymour, writing in the late 1960s, describes Emneth as having “one of the pubs in the Wisbech fruit-growing district that does not display the racialist (and illegal) sign: NO VAN DWELLERS, and consequently it is one of the pubs in which a good time may often be had”. They still grow fruit in the Wisbech district but I cannot vouch for the welcome currently proffered by its pubs.

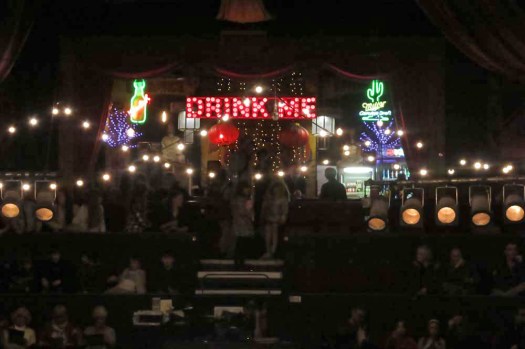

Still reeling from the solar onslaught of the Sun Ra Arkestra the previous night we travelled yesterday to Great Yarmouth to see The Tempest at the town’s Hippodrome Theatre. The

Still reeling from the solar onslaught of the Sun Ra Arkestra the previous night we travelled yesterday to Great Yarmouth to see The Tempest at the town’s Hippodrome Theatre. The  The Tempest took place in another very singular space: the wonderful

The Tempest took place in another very singular space: the wonderful  If the exterior seems full of promise, the interior is even more beguiling: all dark velvet and chocolate brown, and a warm, well-used ambience that has left a rich patina on the fabric of the place. The seating is snug and steeply tiered; its darkly lit corridors lined with old posters and portraits of clowns and past performers, most notably Houdini (where better than Great Yarmouth to demonstrate the art of escapology?). There is even a poster of Houdini in the gents and, while a male toilet in Great Yarmouth is probably not normally the wisest place to take out a camera, my fellow micturators seemed to understand my photographic purpose.

If the exterior seems full of promise, the interior is even more beguiling: all dark velvet and chocolate brown, and a warm, well-used ambience that has left a rich patina on the fabric of the place. The seating is snug and steeply tiered; its darkly lit corridors lined with old posters and portraits of clowns and past performers, most notably Houdini (where better than Great Yarmouth to demonstrate the art of escapology?). There is even a poster of Houdini in the gents and, while a male toilet in Great Yarmouth is probably not normally the wisest place to take out a camera, my fellow micturators seemed to understand my photographic purpose.  Theatre in the round; theatre in the wet: the Hippodrome might have been made for The Tempest; or, given a bit of temporal elasticity that could anticipate three hundred years into the future, The Tempest for the Hippodrome. The production, directed by William Galinsky, Artistic Director of the

Theatre in the round; theatre in the wet: the Hippodrome might have been made for The Tempest; or, given a bit of temporal elasticity that could anticipate three hundred years into the future, The Tempest for the Hippodrome. The production, directed by William Galinsky, Artistic Director of the  Shakespeare is reliably universal of course, but did I detect a whiff of Tarkovsky (Solaris, Stalker) in there? A hint too of Samuel Beckett? Of course, we each bring our own cultural references to bear. Today, yesterday’s performance seems almost dreamlike – a short-lived transportation from reality in which both the drama and the unique properties of the venue itself had an equal part to play. As Prospero remarks:

Shakespeare is reliably universal of course, but did I detect a whiff of Tarkovsky (Solaris, Stalker) in there? A hint too of Samuel Beckett? Of course, we each bring our own cultural references to bear. Today, yesterday’s performance seems almost dreamlike – a short-lived transportation from reality in which both the drama and the unique properties of the venue itself had an equal part to play. As Prospero remarks:

What is it that draws us to the sea; to the coast, the beach? On hot days in summer the answer is fairly obvious: to sunbathe, to swim, to cool off in the sea. Hot summer days are not such a common commodity these days – not in the British Isles anyway – but, whatever the weather brings, people tend to be drawn to the coast like moths to lanterns.

What is it that draws us to the sea; to the coast, the beach? On hot days in summer the answer is fairly obvious: to sunbathe, to swim, to cool off in the sea. Hot summer days are not such a common commodity these days – not in the British Isles anyway – but, whatever the weather brings, people tend to be drawn to the coast like moths to lanterns. Perhaps it is part of an unwritten code of leisure etiquette, something that established itself in the British collective unconscious in Victorian times when those who could afford it caught trains to the newly developed resorts on the coast in order to take the air. The tradition persisted into the 20th century when, given more leisure time and improved public transport, the working classes too could enjoy the same privilege. Nowadays a trip to the coast is a commonplace activity: a Sunday outing, an hour or two spent strolling on the beach, exercising the dog, dragging the children away from the virtual Neverland of their electronic screens.

Perhaps it is part of an unwritten code of leisure etiquette, something that established itself in the British collective unconscious in Victorian times when those who could afford it caught trains to the newly developed resorts on the coast in order to take the air. The tradition persisted into the 20th century when, given more leisure time and improved public transport, the working classes too could enjoy the same privilege. Nowadays a trip to the coast is a commonplace activity: a Sunday outing, an hour or two spent strolling on the beach, exercising the dog, dragging the children away from the virtual Neverland of their electronic screens. But maybe there is something that lies deeper? Some sort of atavistic compulsion to gaze at the sea, to see where we come from, from land masses beyond the horizon, from the primal sludge of the seabed. An urge look at the edge of things where seawater limns the shore and shapes our green island. We are, after all, an island race.

But maybe there is something that lies deeper? Some sort of atavistic compulsion to gaze at the sea, to see where we come from, from land masses beyond the horizon, from the primal sludge of the seabed. An urge look at the edge of things where seawater limns the shore and shapes our green island. We are, after all, an island race. Either way, there is beauty on the beach. Sensuous ripples of sand adorned with calcium necklaces and bangles; the pure white glint of breaking waves. Serried ranks of breakers on the incoming tide, parallels of swell and surf creating a liquid stave for the ocean’s moonstruck music: swash and backwash, the gentle abrasion of pebbles, the faintest tinkle of dead bivalves.

Either way, there is beauty on the beach. Sensuous ripples of sand adorned with calcium necklaces and bangles; the pure white glint of breaking waves. Serried ranks of breakers on the incoming tide, parallels of swell and surf creating a liquid stave for the ocean’s moonstruck music: swash and backwash, the gentle abrasion of pebbles, the faintest tinkle of dead bivalves.

It was the day after the winter solstice – a bright sunny day with the wind from the south, the temperature mild. Conscious of the turning of the year, a last minute escape from the frenzied Christmas build-up seemed appropriate, even if just for a few hours. The north Norfolk coast beckoned – where better to go when days are at their shortest, when the sovereign reign of darkness is turned on its head and the world set aright once more?

It was the day after the winter solstice – a bright sunny day with the wind from the south, the temperature mild. Conscious of the turning of the year, a last minute escape from the frenzied Christmas build-up seemed appropriate, even if just for a few hours. The north Norfolk coast beckoned – where better to go when days are at their shortest, when the sovereign reign of darkness is turned on its head and the world set aright once more? Wells-next-the-Sea was already closing up for Christmas when I left it behind at midday. I followed the coast path east, skirting the salt marshes and mud flats, the pines of East Hills silhouetted on the northern horizon. Scolt Head Island aside – Norfolk’s most northerly territory a little further west, its Ultima Thule – this was the last tract of land at this longitude before reaching the North Pole that lay far beyond the horizon and sunken, sea-drowned Doggerland.

Wells-next-the-Sea was already closing up for Christmas when I left it behind at midday. I followed the coast path east, skirting the salt marshes and mud flats, the pines of East Hills silhouetted on the northern horizon. Scolt Head Island aside – Norfolk’s most northerly territory a little further west, its Ultima Thule – this was the last tract of land at this longitude before reaching the North Pole that lay far beyond the horizon and sunken, sea-drowned Doggerland.  Scattered at regular intervals, poking for invertebrates in the mud were redshanks, curlews and little egrets – the latter once a scarce bird in these parts but now commonplace thanks to climate change. Brent geese, Arctic natives wintering here on this soft-weather shore, were feeding in large groups in the salt marshes. Periodically, without much warning, and honking noisily – the wildest of sounds – they would take to the air to describe a low arc before landing again. A hen harrier, white-rumped and straight-winged, quartering the marshes seemed to go unnoticed by the geese. Focused on much smaller prey, the harrier presented no threat to them – this they knew.

Scattered at regular intervals, poking for invertebrates in the mud were redshanks, curlews and little egrets – the latter once a scarce bird in these parts but now commonplace thanks to climate change. Brent geese, Arctic natives wintering here on this soft-weather shore, were feeding in large groups in the salt marshes. Periodically, without much warning, and honking noisily – the wildest of sounds – they would take to the air to describe a low arc before landing again. A hen harrier, white-rumped and straight-winged, quartering the marshes seemed to go unnoticed by the geese. Focused on much smaller prey, the harrier presented no threat to them – this they knew.  The mildness of the winter was clear to see. This was late December yet gorse bushes were weighed down with mustard yellow blooms. The emerald early growth of Alexanders lined the path edge, and there was even a small, yellow-blushed mushroom, its umbel newly fruited, peering up from the grass. The recent rainfall was quite apparent too – water that had accumulated to render the surface of the path in places to a viscous gravy that made walking hard work.

The mildness of the winter was clear to see. This was late December yet gorse bushes were weighed down with mustard yellow blooms. The emerald early growth of Alexanders lined the path edge, and there was even a small, yellow-blushed mushroom, its umbel newly fruited, peering up from the grass. The recent rainfall was quite apparent too – water that had accumulated to render the surface of the path in places to a viscous gravy that made walking hard work.  After a couple of hours walking, Blakeney Church came into view on the low hill above the harbour, its tower a warning – or a comfort – to sailors of old on this stretch of coast without a lighthouse. Stopping briefly to eat a sandwich on the steps of a boat jetty, my back to the sea, a short-eared owl, another winter visitor, swooped silently past, its unseen quarry somewhere in the wind-rustled reeds.

After a couple of hours walking, Blakeney Church came into view on the low hill above the harbour, its tower a warning – or a comfort – to sailors of old on this stretch of coast without a lighthouse. Stopping briefly to eat a sandwich on the steps of a boat jetty, my back to the sea, a short-eared owl, another winter visitor, swooped silently past, its unseen quarry somewhere in the wind-rustled reeds.  Approaching Blakeney, the moon, almost full, rose over the sea as the sun started setting behind the low ridge that topped the winter wheat fields. It was only three o’clock but already the light was vanishing. But there was change afoot – from now on the days would gradually lengthen and, in perfect solar symmetry, the long winter nights would slowly begin to lose their dark authority.

Approaching Blakeney, the moon, almost full, rose over the sea as the sun started setting behind the low ridge that topped the winter wheat fields. It was only three o’clock but already the light was vanishing. But there was change afoot – from now on the days would gradually lengthen and, in perfect solar symmetry, the long winter nights would slowly begin to lose their dark authority.

A grey morning, late November; a blanket of thick, high-tog cloud slung over the wet flatlands of northeast Norfolk. The day begins serendipitously when, approaching the car park at Horsey Windpump, two distant grey shapes are spotted in a roadside field – grey forms that have enough about them to demand a second look. Binoculars reveal them to be common cranes, an ironic name even here in one of their few British strongholds.

A grey morning, late November; a blanket of thick, high-tog cloud slung over the wet flatlands of northeast Norfolk. The day begins serendipitously when, approaching the car park at Horsey Windpump, two distant grey shapes are spotted in a roadside field – grey forms that have enough about them to demand a second look. Binoculars reveal them to be common cranes, an ironic name even here in one of their few British strongholds. We had, in fact, come to Horsey for the seals. But first, a walk through the marshes alongside Horsey Mere, then to follow the channel of Waxham New Cut before crossing the coast road to Horsey Gap to reach the dunes and the beach. Close to Brograve Mill, a solitary marsh harrier was quartering the reed-beds on the opposite bank. The jackdaws that had gathered on the broken remains of its wooden sail flew off as we approached the mill. Long an icon of the Norfolk Broads, this photogenic ruin looked to be reaching critical mass in its ruination; the brickwork of its tower leaning, Pisa-like, in a losing battle with gravity.

We had, in fact, come to Horsey for the seals. But first, a walk through the marshes alongside Horsey Mere, then to follow the channel of Waxham New Cut before crossing the coast road to Horsey Gap to reach the dunes and the beach. Close to Brograve Mill, a solitary marsh harrier was quartering the reed-beds on the opposite bank. The jackdaws that had gathered on the broken remains of its wooden sail flew off as we approached the mill. Long an icon of the Norfolk Broads, this photogenic ruin looked to be reaching critical mass in its ruination; the brickwork of its tower leaning, Pisa-like, in a losing battle with gravity. The car park at Horsey Gap had its usual compliment of visitors – most folk do not want to have to walk far to fulfill their annual seal pup quota. Clearly it has been a good year for grey seals, with more than 300 newly born pups along this stretch of coast. Signs and plastic ribbon barriers do their best to encourage the over-inquisitive to keep at bay. Grey seals, despite their bulk, are the epitome of vulnerability. On land anyway – slumped on the beach liked huge slugs with lovable Labrador faces, their awkward obese bodies are an encumbrance out of the water.

The car park at Horsey Gap had its usual compliment of visitors – most folk do not want to have to walk far to fulfill their annual seal pup quota. Clearly it has been a good year for grey seals, with more than 300 newly born pups along this stretch of coast. Signs and plastic ribbon barriers do their best to encourage the over-inquisitive to keep at bay. Grey seals, despite their bulk, are the epitome of vulnerability. On land anyway – slumped on the beach liked huge slugs with lovable Labrador faces, their awkward obese bodies are an encumbrance out of the water. The beach action is minimal: an occasional clumsy rolling over; the odd shuffle forward using flippers for traction; sporadic barking and baring of teeth between rival males. The scene looks like an aftermath of overindulgence, bodies adrift on the beach sleeping off the effects of a heavy night. Perhaps it is all that hyper-rich seal milk that explains this torpor: the effort the pups take to digest the 60%-fat fluid, the energy involved in the cows’ synthesising the milk from a diet of fish? Such extreme inactivity brings to mind an assembly of turkey dinner-replete families on Christmas afternoon, individuals sprawled on sofas somnolently waiting for the Queen’s speech. Maybe this is the subliminal reason that so many people come here to see the seals on Boxing Day and New Year’s Day?

The beach action is minimal: an occasional clumsy rolling over; the odd shuffle forward using flippers for traction; sporadic barking and baring of teeth between rival males. The scene looks like an aftermath of overindulgence, bodies adrift on the beach sleeping off the effects of a heavy night. Perhaps it is all that hyper-rich seal milk that explains this torpor: the effort the pups take to digest the 60%-fat fluid, the energy involved in the cows’ synthesising the milk from a diet of fish? Such extreme inactivity brings to mind an assembly of turkey dinner-replete families on Christmas afternoon, individuals sprawled on sofas somnolently waiting for the Queen’s speech. Maybe this is the subliminal reason that so many people come here to see the seals on Boxing Day and New Year’s Day? Heading inland back to the car, the lowering sun finds a gap in the clouds to paint flame red those that lie beneath. We stop for a pint in the pub and, looking out of the window observe a deer, emboldened by the burgeoning dark, casually crossing a field of sugar beet. At the car park, as the last traces of daylight evaporate, three V-shaped formations of geese fly overhead, their high, wild calls preceding the appearance of their silhouettes in the sky.

Heading inland back to the car, the lowering sun finds a gap in the clouds to paint flame red those that lie beneath. We stop for a pint in the pub and, looking out of the window observe a deer, emboldened by the burgeoning dark, casually crossing a field of sugar beet. At the car park, as the last traces of daylight evaporate, three V-shaped formations of geese fly overhead, their high, wild calls preceding the appearance of their silhouettes in the sky.