Just up the road from where I live there is a large black-painted gable wall that bears the legend ‘PINK FLOYD’ in large bold white letters. Clearly, it was a gesture made using good quality paint as it has been there as long as I remember. For all I know it may even date back to the time of the original Pink Floyd line-up with Syd Barrett, although somehow

I doubt it – I rather think it is the work of a fan from the Floyd’s high-profile years of Dark Side of the Moon and after. Since that original graffito was daubed another paintbrush-wielding wag has come along to add a couple more brushstrokes and change the ‘I’ in ‘PINK’ to a slender ‘U’ thus rendering it ‘PUNK’, but this anarchic amendment is not wholly successful, the paint being of insufficient quality to resist natural weathering. One might assume that this addition was made sometime around 1977 but here in Norwich there were individuals sporting orange Mohicans and tartan bondage trouser outfits well into the 1990s. Either way, the gable text seems to be of sufficient permanency that you can almost imagine archaeologists of the future puzzling over the meaning of its ‘Pi(u)nk Floyd’ cipher. Being archaeologists, they will probably attribute it as being of ‘possible

ritualistic significance’.

A little further up the road is a T-junction where the back of a one-way sign has been neatly and inquisitively stencilled: ‘WHY DO YOU DO THIS EACH DAY?’ Years ago, I used to turn left here every morning on my daily drive to work in North Norfolk. The graffito wasn’t there in those days but, had it been, I don’t think I could really have ignored it. It did, after all, pose the very question that was perpetually at the back of my mind and now it seems so significantly placed that I could almost believe that somehow I unconsciously put it there myself – I didn’t.

Putting to one side the familiar and shoddy tagging that seems the imperative of young men wishing to mark their territory like cock-legged dogs, graffiti seems to be at its most potent when a degree of passion is involved. Often it is the unintended permanency of a fleeting emotional state that renders it so evocative. One local piece of graffiti that immediately springs to mind, although I have long forgotten exactly where I saw it, was the legend ‘S. HEWETT IS A HOUR’ (sic), probably the work of a jilted teenage boy

who needs to work on his spelling. Inadvertently, by means of dyslexic subtext, this wounded individual has stated that ‘S. Hewett’, whoever she is, represents a fragment of time – perhaps she really was a waste of time as far as he was concerned. Although this declaration is undoubtedly passionate it seems odd that its author addresses the target of his fury by what seems to be a school register name rather than something more familiar. Maybe he is unknown and unrequited, rather than jilted, and just trying to spread rumours? These days, of course, he would do this by TXT. In contrast to this angry but passionate exclamation, another lovers’ tiff-style message I once saw scrawled on a wall in a neat feminine hand simply stated, ‘CHARLES I DESPISE YOU’. Such withering dispassion would be hard for anyone called Charles to ignore.

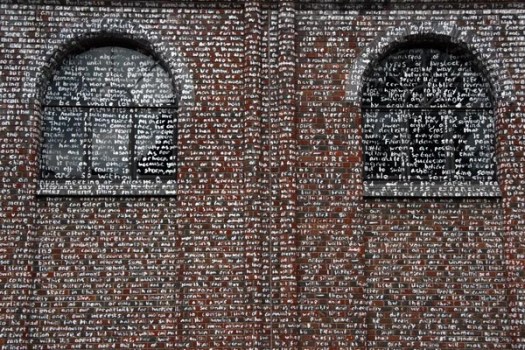

There is a fine line between urban wall scrawling and what might be considered ‘art’ but if you make the text 40,000 words long and legitimise it with an Arts Council grant then it may well become officially sanctioned. This is what the artist Rory Macbeth did in 2006, inscribing the entire text of Sir Thomas More’s 1516 work Utopia on the walls of a derelict building in central Norwich that was due for demolition. As Macbeth rightly states, ‘Most graffiti is utopian’. It should be remembered though that, in Greek, utopia actually means ‘no place’, and not ‘paradise’ as is often supposed.

Visiting Svaneti for the first time I realise that the place I saw in Rudolfsky’s book all those years ago was a collection of villages called Ushguli, nestled beneath high Caucasus peaks and stretching high up a valley. At 2,200 metres altitude, Ushguli is probably the highest permanently inhabited settlement in Europe (although currently no-go Dagestan on the other side of the Caucasus range also has contenders to the title) but it is its magnificent medieval towers that make it truly extraordinary. Some have collapsed over the years but there still sufficient to present an imposing spectacle and render Ushguli’s towers a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Visiting Svaneti for the first time I realise that the place I saw in Rudolfsky’s book all those years ago was a collection of villages called Ushguli, nestled beneath high Caucasus peaks and stretching high up a valley. At 2,200 metres altitude, Ushguli is probably the highest permanently inhabited settlement in Europe (although currently no-go Dagestan on the other side of the Caucasus range also has contenders to the title) but it is its magnificent medieval towers that make it truly extraordinary. Some have collapsed over the years but there still sufficient to present an imposing spectacle and render Ushguli’s towers a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

![295[1]](https://eastofelveden.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/2951.jpg?w=525)