I wander thro’ each charter’d street,

Near where the charter’d Thames does flow.

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

William Blake London

Last week I paid a visit to London to go and see the Blake exhibition at Tate Britain. Every visit to London – not so frequent these days – seems to reveal yet more new building projects, more cranes on the skyline, more high blue fences. Multinational finance keen to invest in real estate seems intent on filling in any remaining gaps, such as they are, with new buildings – a new transistor soldered onto the crowded circuit board that is hi-rise central London. Each new piece of architectural bling serves as a totem to (someone else’s) capital. Meanwhile, the people on the street, who hurry between meetings, or stand hunched smoking and phone-swiping outside revolving glass doors, appear indifferent to the edifices that rise above them as if they were little more than fill-in detail on an architect’s plan.

The affect can be alienating. I cannot relate to any of this: my own navigation of the city depends on outdated mental maps and more familiar topography. Peering through the few remaining gaps in the crowded cityscape I am at least able to identify some landmarks by their distinctive form or superior height – the London Stadium fronted by Anish Kapoor’s helter-skelter Orbit sculpture, the Shard, the Gherkin, the pyramid-topped One Canada Square. But even these relatively familiar sights are less old friends than over-enthusiastic schoolboys with their hands up – ‘Me, Sir! Me, Sir!’

I have to face it: this is not my city. But whose is it? Who does it speak to?

Two hundred or so years ago, London spoke to William Blake but the city he lived in has now largely vanished. All that remains is location and shabbily dressed ghosts. In 1820 – exactly two hundred years ago – Blake moved with his wife Catherine to the last place they would live together, a house at Fountain Court off the Strand. It was here, approaching the end of his life, where he experienced his most profound visions, and where he was judged – the jury will always be out – to be either genius or madman. While living here he must have come close to bumping into fellow traveller (and ‘madman’) John Clare, who on one of his rare visits to the capital lodged nearby, although no such meeting has been recorded. The pair had much in common – Blake, an engraver, artist, poet; Clare, a labourer, fence-builder, poet. Both visionaries of sorts, both opposed to militarism and empire, both horrified by the desecration they saw coming in the guise of the Industrial Revolution.

Coming out of the exhibition, almost cross-eyed from hours of peering at intricate artwork and deciphering Lilliputian script in low light, my friend Nigel Roberts remarked that it was actually a good thing that nothing remained of any of Blake’s London homes – his legacy was one of pure spirit. All that marked his various residences was its former address (if the street still existed) and an optional blue plaque. Even the monument at Bunhill Fields (a place I had visited defiantly on the day they buried Margaret Thatcher, an anti-Blake figure if ever there was one) was merely a memorial stone not a grave marker. The common grave he was actually buried in went unmarked until August 2018, when a ledger stone was finally put in place with the legend: Here lies William Blake 1757—1827 Poet Artist Prophet.

What did remain, in addition to an enormous body of work and a roll-call of sacred locations, was Blake’s indelible imprint on the city. Like a sleeping giant, any future London, however changed or corrupted its topography, would invariably retain a Blakean spirit, a spirit that could be evoked on demand. Blake’s legacy does not depend on bricks and mortar. Here was a man who could see a world in a grain of sand, and angels in a tree at Peckham Rye.

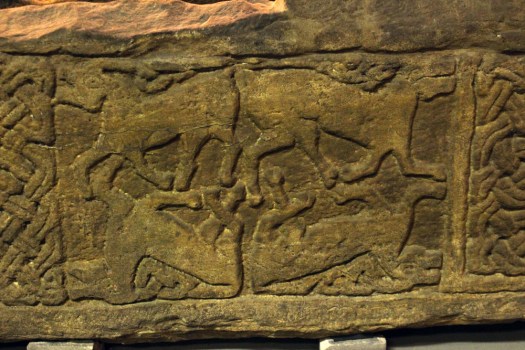

The stones are arranged around the church interior so as to make a circuit. There is intricate Celtic lattice work on the first two – the ‘Sun Stone’ and the Jordanhill Cross – and on the third, the ‘Cuddy Stane’, a representation of a man on a horse, or possibly a donkey (‘cuddy’) bearing a Christ figure. A group of five Viking hogbacks, dark and heavy, and resembling those giant slugs that sometimes venture out along garden paths after rain, dominate the transept. Unnoticed until is pointed out to us, the paws of a supine bear clutch one of the stones at its corners, a complex symbol that combines animal strength and tenderness and might, perhaps, relate to the high-ranking Viking it commemorates. The highlight of the collection is probably the Govan Sarcophagus, the only one of its kind from the pre-Norman era, which was unearthed in the graveyard in 1855. This intricately carved structure is thought to have once held the remains of King Constantine himself, although its symbols suggest that is more likely to have been made a couple of centuries after his death. Elsewhere are ancient stones that have been recycled as markers for later graves – palimpsests where earlier detail has been erased to allow a new name to be cut into the stone.

The stones are arranged around the church interior so as to make a circuit. There is intricate Celtic lattice work on the first two – the ‘Sun Stone’ and the Jordanhill Cross – and on the third, the ‘Cuddy Stane’, a representation of a man on a horse, or possibly a donkey (‘cuddy’) bearing a Christ figure. A group of five Viking hogbacks, dark and heavy, and resembling those giant slugs that sometimes venture out along garden paths after rain, dominate the transept. Unnoticed until is pointed out to us, the paws of a supine bear clutch one of the stones at its corners, a complex symbol that combines animal strength and tenderness and might, perhaps, relate to the high-ranking Viking it commemorates. The highlight of the collection is probably the Govan Sarcophagus, the only one of its kind from the pre-Norman era, which was unearthed in the graveyard in 1855. This intricately carved structure is thought to have once held the remains of King Constantine himself, although its symbols suggest that is more likely to have been made a couple of centuries after his death. Elsewhere are ancient stones that have been recycled as markers for later graves – palimpsests where earlier detail has been erased to allow a new name to be cut into the stone.

What do you do on a drizzly grey day in Berlin? A midwinter day when the sun is enfeebled and hidden, cowering somewhere beneath a thick duvet of cloud. What do you do in a city that you do not know well and only have experience of in winter?

What do you do on a drizzly grey day in Berlin? A midwinter day when the sun is enfeebled and hidden, cowering somewhere beneath a thick duvet of cloud. What do you do in a city that you do not know well and only have experience of in winter?

The Saints is a small, loosely defined area of northeast Suffolk just south of the River Waveney and the Norfolk border. Effectively it is a fairly unremarkable patch of arable countryside that contains within it a baker’s dozen of small villages with names that begin or end with the name of the parish saint: St Peter South Elmham, St Michael South Elmham, St Nicholas South Elmham, St James South Elmham, St Margaret South Elmham, St Mary South Elmham, St Cross South Elmham, All Saints South Elmham, Ilketshall St Andrew, Ilketshall St Lawrence, Ilketshall St Margaret, Ilketshall St John and All Saints Mettingham. The area is bisected in its eastern fringe by the Bungay—Halesworth road that follows the course of Stone Street, a die-straight Roman construction, one of several that can still be traced on any road map of East Anglia. On the whole though the roads around here are anything but Roman in character: narrow, twisting, often bewilderingly changing direction, and marked with confusing signs (too many saints!), it is a good place to visit should you wish to humiliate your Sat Nav. John Seymour in The Companion Guide to East Anglia (1968) describes The Saints as ‘a hillbilly land into which nobody penetrates unless he has good business,’ which is perhaps hyperbolic but there is undoubtedly a feel of liminality to the area that persists to this day.

The Saints is a small, loosely defined area of northeast Suffolk just south of the River Waveney and the Norfolk border. Effectively it is a fairly unremarkable patch of arable countryside that contains within it a baker’s dozen of small villages with names that begin or end with the name of the parish saint: St Peter South Elmham, St Michael South Elmham, St Nicholas South Elmham, St James South Elmham, St Margaret South Elmham, St Mary South Elmham, St Cross South Elmham, All Saints South Elmham, Ilketshall St Andrew, Ilketshall St Lawrence, Ilketshall St Margaret, Ilketshall St John and All Saints Mettingham. The area is bisected in its eastern fringe by the Bungay—Halesworth road that follows the course of Stone Street, a die-straight Roman construction, one of several that can still be traced on any road map of East Anglia. On the whole though the roads around here are anything but Roman in character: narrow, twisting, often bewilderingly changing direction, and marked with confusing signs (too many saints!), it is a good place to visit should you wish to humiliate your Sat Nav. John Seymour in The Companion Guide to East Anglia (1968) describes The Saints as ‘a hillbilly land into which nobody penetrates unless he has good business,’ which is perhaps hyperbolic but there is undoubtedly a feel of liminality to the area that persists to this day.  The village names conjure a medieval world where saint-obsessed religion loomed large. Such a tight cluster of settlements suggests a concentration of population where parishes might eventually combine to form a town or city – with 13 villages and the same number of churches (eleven of which are extant), there were more churches here than in all of Cambridge. But The Saints never coalesced to become a medieval city – none of the villages had a port, defensive structure or even significant market to its credit and consequently the area would slowly slip into obscurity as the medieval era played out and other East Anglia towns and cities – Cambridge, Bury St Edmunds, Ipswich and, of course, Norwich – took the baton of influence and power.

The village names conjure a medieval world where saint-obsessed religion loomed large. Such a tight cluster of settlements suggests a concentration of population where parishes might eventually combine to form a town or city – with 13 villages and the same number of churches (eleven of which are extant), there were more churches here than in all of Cambridge. But The Saints never coalesced to become a medieval city – none of the villages had a port, defensive structure or even significant market to its credit and consequently the area would slowly slip into obscurity as the medieval era played out and other East Anglia towns and cities – Cambridge, Bury St Edmunds, Ipswich and, of course, Norwich – took the baton of influence and power.  It was not always so: one of the villages in particular held great significance in its day. The land covered by the South Elmham parishes was once owned by Almar, Bishop of East Anglia and the late Saxon Bishops of Norwich had a summer palace here at St Cross, now South Elmham Hall. The most intriguing of the churches lies within the same parish. It is not in any way complete but a ruin framed by woodland a good half mile from the nearest road. South Elmham Minster, although probably never a minster proper, is veiled in mystery regarding its origins but its appeal owes as much to its half-hidden location as it does to its obscure history. South Elmham may have once been the seat of the second East Anglian bishopric (the first was in Dunwich, the sea-ravaged village on the Suffolk coast), although North Elmham in Norfolk seems a more likely contender. Whatever the ruin’s original function – a private chapel for Herbert de Losinga, Norwich’s first bishop, is another possibility, or it may even be that a second bishopric was founded here – the church in the wood just south of South Elmham Hall dates back at least to the 11th century. It is probably older in origin – a ninth-century gravestone has been unearthed in its foundations. The site itself is undoubtedly of greater antiquity: a continuation of an earlier Anglo-Saxon presence that occupied the same moated site, which, earlier still, was home to a Roman temple and perhaps, even earlier, a pagan holy place.

It was not always so: one of the villages in particular held great significance in its day. The land covered by the South Elmham parishes was once owned by Almar, Bishop of East Anglia and the late Saxon Bishops of Norwich had a summer palace here at St Cross, now South Elmham Hall. The most intriguing of the churches lies within the same parish. It is not in any way complete but a ruin framed by woodland a good half mile from the nearest road. South Elmham Minster, although probably never a minster proper, is veiled in mystery regarding its origins but its appeal owes as much to its half-hidden location as it does to its obscure history. South Elmham may have once been the seat of the second East Anglian bishopric (the first was in Dunwich, the sea-ravaged village on the Suffolk coast), although North Elmham in Norfolk seems a more likely contender. Whatever the ruin’s original function – a private chapel for Herbert de Losinga, Norwich’s first bishop, is another possibility, or it may even be that a second bishopric was founded here – the church in the wood just south of South Elmham Hall dates back at least to the 11th century. It is probably older in origin – a ninth-century gravestone has been unearthed in its foundations. The site itself is undoubtedly of greater antiquity: a continuation of an earlier Anglo-Saxon presence that occupied the same moated site, which, earlier still, was home to a Roman temple and perhaps, even earlier, a pagan holy place.  We leave the car in a muddy parking area alongside another vehicle and a dumped piece of agricultural machinery. Nearby stands a weather-beaten trestle table that suggests that this once might have served as a designated picnic spot. Now half-submerged in grass and thistles, the table did not look as if any sandwich boxes had been opened on it for some time. Things have changed here a little in recent years: the permissive footpaths that once threaded through the South Elmham estate are no longer available for the public, and the hall itself has been re-purposed for use as a wedding and conference venue. At least the minster was still accessible by means of a green lane and a public footpath across fields.

We leave the car in a muddy parking area alongside another vehicle and a dumped piece of agricultural machinery. Nearby stands a weather-beaten trestle table that suggests that this once might have served as a designated picnic spot. Now half-submerged in grass and thistles, the table did not look as if any sandwich boxes had been opened on it for some time. Things have changed here a little in recent years: the permissive footpaths that once threaded through the South Elmham estate are no longer available for the public, and the hall itself has been re-purposed for use as a wedding and conference venue. At least the minster was still accessible by means of a green lane and a public footpath across fields.  The green lane is flanked by mature hedges frothed white with blackthorn blossom. Reaching its bottom end we turn left to follow a footpath alongside a stream, a minor tributary of the River Waveney; strange hollowed-out hornbeams measure out its bank. Soon we come to the copse that contains the ruin, a rusty gate gives admission across a partial moat and raised bank into what can only be described as a woodland glade. The ancient flint walls of the church stand central, striated by the shadow of hornbeams still leafless in late March. There is no sign of a roof but the weathered walls of the nave are clear in outline, as is the single entrance to the west. On the ground, last year’s fallen leaves provide a soft bronze carpet that is mostly devoid of ground plants.

The green lane is flanked by mature hedges frothed white with blackthorn blossom. Reaching its bottom end we turn left to follow a footpath alongside a stream, a minor tributary of the River Waveney; strange hollowed-out hornbeams measure out its bank. Soon we come to the copse that contains the ruin, a rusty gate gives admission across a partial moat and raised bank into what can only be described as a woodland glade. The ancient flint walls of the church stand central, striated by the shadow of hornbeams still leafless in late March. There is no sign of a roof but the weathered walls of the nave are clear in outline, as is the single entrance to the west. On the ground, last year’s fallen leaves provide a soft bronze carpet that is mostly devoid of ground plants.  Church or not, there is a timelessness to this place in the woods. And a strong sense of genius loci, the sort of thing that put the wind up the Romans with their straight lines and four-square militaristic outlook. I wander off to explore the bank to the west and discover the opening of a badger sett that looks to be newly excavated. Without much expectation, I rummage though the spoil musing that there might just be the remotest of chances that, burrowing deep beneath the mound, the animals have thrown up some treasure long buried in the soil below: an Anglo-Saxon torc, a Roman coin perhaps? I would even settle for a rusty button, but nothing. No matter, the mystery of the place is enough for now. We leave the bosky comfort of the site and retrace our steps along the beck and green lane back to the car. The other car has gone – we never did see its occupants.

Church or not, there is a timelessness to this place in the woods. And a strong sense of genius loci, the sort of thing that put the wind up the Romans with their straight lines and four-square militaristic outlook. I wander off to explore the bank to the west and discover the opening of a badger sett that looks to be newly excavated. Without much expectation, I rummage though the spoil musing that there might just be the remotest of chances that, burrowing deep beneath the mound, the animals have thrown up some treasure long buried in the soil below: an Anglo-Saxon torc, a Roman coin perhaps? I would even settle for a rusty button, but nothing. No matter, the mystery of the place is enough for now. We leave the bosky comfort of the site and retrace our steps along the beck and green lane back to the car. The other car has gone – we never did see its occupants.

Today is St Patrick’s Day and March 17 is the supposed date of the 5th-century missionary’s death. Patrick was the forerunner of many early missionaries who came to Irish shores to preach Christianity, the island more receptive to new ideas about religion than its larger neighbour to the east across the Irish Sea. Consequently Ireland abounds with relics and ruins of early Christianity, sometimes in the most improbable of places.

Today is St Patrick’s Day and March 17 is the supposed date of the 5th-century missionary’s death. Patrick was the forerunner of many early missionaries who came to Irish shores to preach Christianity, the island more receptive to new ideas about religion than its larger neighbour to the east across the Irish Sea. Consequently Ireland abounds with relics and ruins of early Christianity, sometimes in the most improbable of places. Sailing around Ireland’s southwest coast, skirting the peninsulas that splay out from the Kerry coast, the two islands of the Skelligs come into view after rounding Bolus Head at the end of the Inveragh Peninsula. Both islands are sheer, with sharp-finned summits that resemble inverted boat keels. The smaller of the two appears largely white at first but increasing proximity reveals that the albino effect is down to a combination of nesting gannets and guano. The acrid tang of ammonia on the breeze and distant cacophony announce the presence of the birds well before the identity of any individual can be confirmed by binoculars.

Sailing around Ireland’s southwest coast, skirting the peninsulas that splay out from the Kerry coast, the two islands of the Skelligs come into view after rounding Bolus Head at the end of the Inveragh Peninsula. Both islands are sheer, with sharp-finned summits that resemble inverted boat keels. The smaller of the two appears largely white at first but increasing proximity reveals that the albino effect is down to a combination of nesting gannets and guano. The acrid tang of ammonia on the breeze and distant cacophony announce the presence of the birds well before the identity of any individual can be confirmed by binoculars. As the boat draws closer, the sheer volume of birds – gannets, fulmars, puffins, terns – becomes plain to see. With something like 70,000 birds, Little Skellig is the second largest gannet colony in the world. But on the larger island of Skellig Michael, although seabirds abound here too, there is also the suggestion of a human presence, albeit an historic one. High up in the rocks, small stone structures can be discerned: rounded domes that are clearly man-made and which soften the jagged silhouette of the island’s summit. These are beehive cells, the dry-stone oratories favoured by early Irish monks for their meditation. Sitting aloft the island on a high terrace, commanding a panoramic view over the Atlantic Ocean in one direction and the fractal Kerry coast in the other, these simple stone cells came without windows – the business was one of prayer and meditation not horizon-gazing. Such isolation was necessary for reasons of both safety and spirituality. And Skellig Michael was the acme of isolation. In the early Christian milieu the Skellig Islands, facing the seemingly limitless Atlantic off the southwest coast of Ireland, were more than merely remote: they were at the very edge of the known world.

As the boat draws closer, the sheer volume of birds – gannets, fulmars, puffins, terns – becomes plain to see. With something like 70,000 birds, Little Skellig is the second largest gannet colony in the world. But on the larger island of Skellig Michael, although seabirds abound here too, there is also the suggestion of a human presence, albeit an historic one. High up in the rocks, small stone structures can be discerned: rounded domes that are clearly man-made and which soften the jagged silhouette of the island’s summit. These are beehive cells, the dry-stone oratories favoured by early Irish monks for their meditation. Sitting aloft the island on a high terrace, commanding a panoramic view over the Atlantic Ocean in one direction and the fractal Kerry coast in the other, these simple stone cells came without windows – the business was one of prayer and meditation not horizon-gazing. Such isolation was necessary for reasons of both safety and spirituality. And Skellig Michael was the acme of isolation. In the early Christian milieu the Skellig Islands, facing the seemingly limitless Atlantic off the southwest coast of Ireland, were more than merely remote: they were at the very edge of the known world. The island’s monastic site is infused with mystery, as all good ruins are, but is thought to have been established in the 6th century by Saint Fionán. Consisting of six beehive cells, two oratories and a later medieval church, the site occupies a stone terrace 600 feet above the swirling green waters of the sea below.

The island’s monastic site is infused with mystery, as all good ruins are, but is thought to have been established in the 6th century by Saint Fionán. Consisting of six beehive cells, two oratories and a later medieval church, the site occupies a stone terrace 600 feet above the swirling green waters of the sea below. Skirting Skellig Michael, a landing stage with a helicopter pad comes into view. A vertiginous path of stone steps leads up towards the beehive huts close to the island’s mountain-like summit. We do not disembark. Instead we keep sailing, bound for a safer harbour in Glengarriff in County Cork. No matter, the sight of the rocks, the winding, climbing path and the austere cells on the terrace at the top is already imprinted on our memory.

Skirting Skellig Michael, a landing stage with a helicopter pad comes into view. A vertiginous path of stone steps leads up towards the beehive huts close to the island’s mountain-like summit. We do not disembark. Instead we keep sailing, bound for a safer harbour in Glengarriff in County Cork. No matter, the sight of the rocks, the winding, climbing path and the austere cells on the terrace at the top is already imprinted on our memory. Without doubt this was a life of supreme hardship: the isolation, the relentless diet of fish and seabird eggs, the ever-battering wind and salt-spray. Such was the isolation, and so extreme the privations of this beatific pursuit, that one might assume that the monks would have been left in peace to practice their calling. This was not to be. Viking raiders arrived here in the early 9th century and took the trouble to land, scale the island’s heights and attack the monks. For most of us it is probably difficult to comprehend the blind-rage fury of the raiders, the wrath invoked in them by pious upstarts with their new Christian God. Easier perhaps is to imagine the dread that must have been felt by the monks as the Vikings approached their spiritual eyrie.

Without doubt this was a life of supreme hardship: the isolation, the relentless diet of fish and seabird eggs, the ever-battering wind and salt-spray. Such was the isolation, and so extreme the privations of this beatific pursuit, that one might assume that the monks would have been left in peace to practice their calling. This was not to be. Viking raiders arrived here in the early 9th century and took the trouble to land, scale the island’s heights and attack the monks. For most of us it is probably difficult to comprehend the blind-rage fury of the raiders, the wrath invoked in them by pious upstarts with their new Christian God. Easier perhaps is to imagine the dread that must have been felt by the monks as the Vikings approached their spiritual eyrie.

If trees could only speak. If they had some semblance of sentience and memory, and a means of communication, what would they tell us? Ancient trees – or at least those we suspect to be very old – are usually described in terms of human history. Perhaps as humans it is hubris that requires us to define them in this way but the fact is that by and large they tend to outlive us: many lofty oaks that stand today were already reaching for the sky when the Industrial Revolution changed the face of the land over two centuries ago. This linkage of history and old trees has resulted in some colourful local history. The story of the future King Charles II hiding from parliamentarian troops up a pollarded oak tree in Boscobel, Shropshire carried sufficient potency for the original tree to have been eventually killed by souvenir hunters excessively lopping of its branches as keepsakes. Undoubtedly the stuff of legend, Royal Oak ended up becoming the third commonest pub name in England. A long-established folk belief also tells of the Glastonbury Thorn, the tree which is said to have grown from the staff of Joseph of Arithmathea whom legend has it once visited Glastonbury with the Holy Grail. What was considered to be the original tree perished during the English Civil War, chopped down and burned by Cromwell’s troops who clearly held a grudge against any tree that came with spiritual associations or historical attitude.

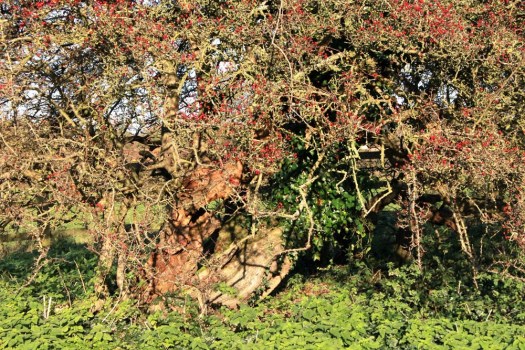

If trees could only speak. If they had some semblance of sentience and memory, and a means of communication, what would they tell us? Ancient trees – or at least those we suspect to be very old – are usually described in terms of human history. Perhaps as humans it is hubris that requires us to define them in this way but the fact is that by and large they tend to outlive us: many lofty oaks that stand today were already reaching for the sky when the Industrial Revolution changed the face of the land over two centuries ago. This linkage of history and old trees has resulted in some colourful local history. The story of the future King Charles II hiding from parliamentarian troops up a pollarded oak tree in Boscobel, Shropshire carried sufficient potency for the original tree to have been eventually killed by souvenir hunters excessively lopping of its branches as keepsakes. Undoubtedly the stuff of legend, Royal Oak ended up becoming the third commonest pub name in England. A long-established folk belief also tells of the Glastonbury Thorn, the tree which is said to have grown from the staff of Joseph of Arithmathea whom legend has it once visited Glastonbury with the Holy Grail. What was considered to be the original tree perished during the English Civil War, chopped down and burned by Cromwell’s troops who clearly held a grudge against any tree that came with spiritual associations or historical attitude. There is an ancient thorn in Norfolk that is sometimes connected with the same Joseph of Arithmathea myth. Hethel Old Thorn can be found along narrow lanes amidst unremarkable farming country 10 miles south of Norwich. Close to the better known

There is an ancient thorn in Norfolk that is sometimes connected with the same Joseph of Arithmathea myth. Hethel Old Thorn can be found along narrow lanes amidst unremarkable farming country 10 miles south of Norwich. Close to the better known  At an estimated 700 years old this is thought to be the oldest specimen of Crataegus monogyna in the UK. Like the nearby Kett’s Oak, the thorn was thought to be a meeting place for the rebels during

At an estimated 700 years old this is thought to be the oldest specimen of Crataegus monogyna in the UK. Like the nearby Kett’s Oak, the thorn was thought to be a meeting place for the rebels during