The road to Dirē Dawa is a long one: an eight-hour drive from Addis Ababa, or so we are told.

We left Addis Ababa at dawn, our bus rattling through empty streets shadowed by new-build office blocks. As with almost everywhere currently in Ethiopia, the pavements were piled with concrete rubble, the result of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s ambitious nationwide road-widening project, a controversial scheme that had already demolished parts of some poorer city districts and displaced many residents in its wake.

For the first hour or so we sped along a pristine tarmacked dual carriageway, the brightening horizon ahead weighed down by clouds the colour of watermelon juice. We could have been almost anywhere; or, at least, anywhere that comes blessed with a backdrop of purple-shadowed mountains and lush tropical greenery. Eventually the freeway morphed into a narrow two-lane highway, which meandered around the heads of valleys as we plied our way eastwards. Traffic was heavy in both directions. Coming towards us was an endless stream of heavily laden trucks from Djibouti, each one towing a trailer, vehicle and driver bonded in lockstep like driven cattle. We slotted into a gap in the fast moving crocodile of trucks that were heading east towards the coast, some of which were piggybacking another truck strapped to their flatbed.

As elsewhere in the country there were checkpoints and roadblocks to slow things down. We had already experienced these travelling the roads of the south, especially in Oromia state, although they had rarely delayed us for long. Sometimes they were administered by the Ethiopian army but more often than not they were manned by local militia who wanted to keep an eye on who was coming into their territory. It had not taken long in the country to come to the conclusion that, rather than the unified sense of national identity promoted by the government, Ethiopia was in the process of becoming increasingly fragmented by region, language, culture and political persuasion.

Before our arrival in Ethiopia we had made firm decisions as to our itinerary. These were based on information gleaned from online travel forums and British FCO warnings regarding more unstable areas of the country. Much of the north – the highlands of Amhara and part of Tigray – was considered unsafe because of rebel activity and kidnappings. Similarly, part of the large sprawling region of Oromia that fans south, west and east from Addis Ababa also came with similar warnings about safety. The FCO had produced a map of the country that divided the country into three zones according to perceived safety: red (‘Advise against all travel’), amber (‘Advise against all but essential travel’) and green (‘see our travel advice before travelling’). I had consulted the updated map frequently throughout the second half of 2024 in the vain hope that brotherly love might prevail throughout the land but the map did not appear to change very much. Much of the south, in particularly the area around Hawassa where we had spent the previous week, was largely amber and therefore considered relatively safe. The highway between Addis Ababa and Dirē Dawa appeared to pass through both amber and green zones, nudging the red briefly between the Oromia towns of Welenchiti and Metehara.

Road blocks and heavy traffic aside, the other barrier to easy progress was roaming animals – donkeys, goats and camels. The donkeys especially were a law unto themselves, totally unfazed by the vehicles that swerved around them as they pottered along oblivious to any danger. It seemed almost as if the animals understood the fast and loose rules of the road – fully aware that if they were harmed then their owners would require compensation from the guilty driver. On a couple of occasions I actually saw one cross the road using a zebra crossing. Camels were a different matter though, large enough to call the shots, they were generally unwilling to step aside or allow any vehicle to manoeuvre past them.

We passed through an endless parade of villages that had little to differentiate themselves from one other: a blurred flash-by of roadside settlements, all flimsy housing and lean-do shops thrown together out of scrap wood, plastic sheets and corrugated iron. The goods on sale – fruit and vegetables, flyblown meat, second hand clothes, spare parts for vehicles – were the bread and butter (or, perhaps, injera) of everyday life. As always in the Global South, it was intriguing how such a base-level financial system managed to thrive, a poor man’s economy in which ragged ten birr notes continually changed hands until all the value had been squeezed out of them.

There was another product on sale that seemed to be ubiquitous in this part of the world – we had seen it on display along almost every roadside in southern Ethiopia the previous week. Khat, the stimulant of choice across much of the Horn of Africa, is an innocuous looking leaf that resembles bay or privet. Legal throughout the region, khat is, as many Ethiopians will attest, less a stimulant, more a way of life. Our driver was clearly an aficionado; as was our guide, a young man who kept his own counsel throughout the journey and did not utter a word of information about the foreign (to us) country that lay beyond the window. The pair just stared ahead for the whole way, locked in herbal reverie as they slowly worked through the pile of leaves that lay at their elbow.

Khat seems to be very much a driving drug, an herbal alternative to the so-called energy drinks whose slim cans over-caffeinated motorists toss out of their windows along Britain’s motorways. It might even be considered to be a green alternative to caffeine, although there is absolutely no shortage of coffee in this land of stay-awake plenty. A week earlier, motoring through the coffee-rich Sidama region of the south, our previous guide, Wonde (‘Wander’), had regaled us with horror stories about khat-crazed drivers careering off the road due to lack of sleep and/or poor decision-making. It seemed perfectly believable. Between Addis and Dirē Dawa I counted at least eight trucks that had crashed and gone off-the-road; some lay forlornly on their side, while others had ended up completely upside down with wheels akimbo. It was unclear as to what had become of the drivers, although it did not look as if they would have escaped unscathed.

One crashed truck that we passed had unleashed a load of crated beer bottles onto the slope beside the road. Slowing down to make our way around the crowd that had gathered around the wrecked vehicle, the air smelled as malty as a Sunday morning pub. A couple of armed men were guarding the booty as approved wreckers sifted through the debris, placing the unbroken bottles in crates ready for resale. Who the men with guns were was anybody’s guess. It was the same at some of the checkpoints we were obliged to stop at, where youths with rifles peered inside the bus before lowering the barrier – no more than a rope stretched across the road – to allow us to pass. A single word from the driver, ‘Turist’, and a glance at our pale well-fed faces within, was usually sufficient for us to be waved on.

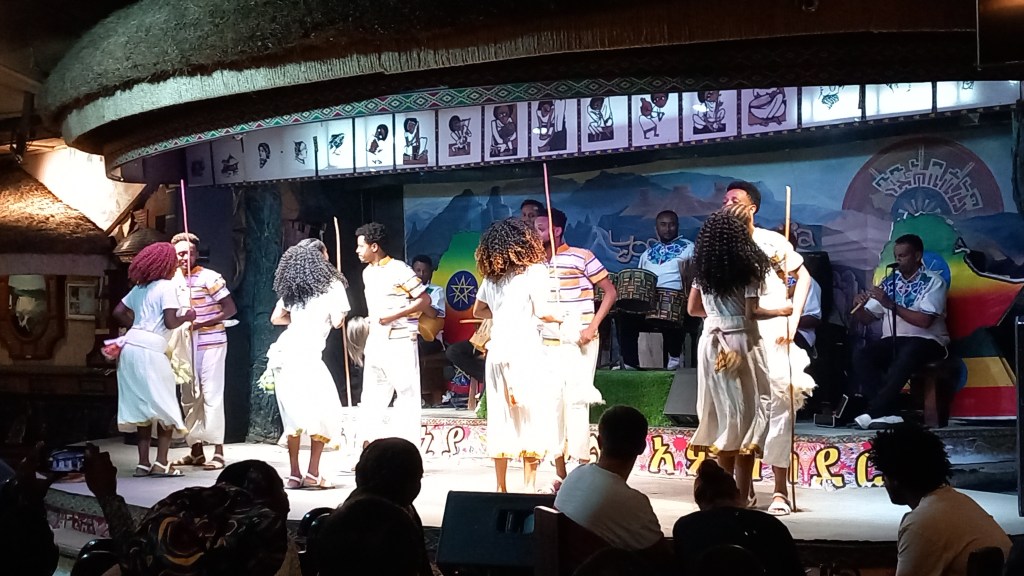

While khat consumption is widespread, it was something that was shared with other countries in the region like Somalia. Other aspects of Ethiopian culture are decidedly more unique. One is the country’s unorthodox calendar, which is seven or eight years behind the rest of the world. While the year elsewhere might be 2024 according to the Gregorian calendar, in Ethiopia it is currently 2017. ‘Welcome to Ethiopia, and congratulations,’ we had been told more than once, ‘here you are seven years younger.’ Another Ethiopian curiosity is the music that is played loud and proud almost everywhere, which whether traditional, pop, or the rather wonderful Ethio-Jazz that I had already developed a taste for, uses a pentatonic scale that has a distinctive modal sound to it. A world away from other African music that is generally more accessible to Western ears, Ethiopian music has a tendency to sound rather other-worldly and even a little Chinese at times.

Another facet of Ethiopian culture that sets the country apart is the food, which is quite unlike anywhere else. The mainstay of the diet is a sour spongy pancake called injera, which is made from an ancient indigenous grain called teff. This is eaten along with small helpings of spicy vegetable or meat sauces. For many Ethiopians, if they can afford it, kitfo (spicy raw beef) is the preferred accompaniment, although, perhaps counter-intuitively, there are actually two days of the week, Wednesday and Friday, when restaurants are obliged to serve only ‘fasting’ food, which is strictly vegan. Whether meat or vegetable, raw or cooked, freshness is probably the most important factor in regards to health, and I believe it was the suspicious, rather tired-looking sauce that came with the injera I had eaten the previous night in Addis that had been the cause of the stomach cramps that troubled me throughout the long journey.

We pulled into Dirē Dawa just as it was becoming dark, the onset of the city’s flickering neon countering the rapid tropical plunge into night. The journey had taken twelve hours – sunrise to sunset. Considerably lower in altitude than where we had come from, the city felt hot and humid compared to Addis’s fresher, spring-like climate. But it was as bustling and noisy as the capital, with a honking stream of three–wheel bajajs (tuk-tuks) plying Dirē Dawa’s wide boulevards. Tomorrow there would be the opportunity to visit the city’s sights, such as they were. Tonight though, after a day of unremitting motion, it was the promise of laying still on an immobile bed that held the greatest appeal.

Ferris wheel, Toktogul, Kyrgyzstan

Ferris wheel, Toktogul, Kyrgyzstan View of Manas Square from Bishkek Ferris wheel, Kyrgyzstan

View of Manas Square from Bishkek Ferris wheel, Kyrgyzstan Panfilov Park, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

Panfilov Park, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

The stones are arranged around the church interior so as to make a circuit. There is intricate Celtic lattice work on the first two – the ‘Sun Stone’ and the Jordanhill Cross – and on the third, the ‘Cuddy Stane’, a representation of a man on a horse, or possibly a donkey (‘cuddy’) bearing a Christ figure. A group of five Viking hogbacks, dark and heavy, and resembling those giant slugs that sometimes venture out along garden paths after rain, dominate the transept. Unnoticed until is pointed out to us, the paws of a supine bear clutch one of the stones at its corners, a complex symbol that combines animal strength and tenderness and might, perhaps, relate to the high-ranking Viking it commemorates. The highlight of the collection is probably the Govan Sarcophagus, the only one of its kind from the pre-Norman era, which was unearthed in the graveyard in 1855. This intricately carved structure is thought to have once held the remains of King Constantine himself, although its symbols suggest that is more likely to have been made a couple of centuries after his death. Elsewhere are ancient stones that have been recycled as markers for later graves – palimpsests where earlier detail has been erased to allow a new name to be cut into the stone.

The stones are arranged around the church interior so as to make a circuit. There is intricate Celtic lattice work on the first two – the ‘Sun Stone’ and the Jordanhill Cross – and on the third, the ‘Cuddy Stane’, a representation of a man on a horse, or possibly a donkey (‘cuddy’) bearing a Christ figure. A group of five Viking hogbacks, dark and heavy, and resembling those giant slugs that sometimes venture out along garden paths after rain, dominate the transept. Unnoticed until is pointed out to us, the paws of a supine bear clutch one of the stones at its corners, a complex symbol that combines animal strength and tenderness and might, perhaps, relate to the high-ranking Viking it commemorates. The highlight of the collection is probably the Govan Sarcophagus, the only one of its kind from the pre-Norman era, which was unearthed in the graveyard in 1855. This intricately carved structure is thought to have once held the remains of King Constantine himself, although its symbols suggest that is more likely to have been made a couple of centuries after his death. Elsewhere are ancient stones that have been recycled as markers for later graves – palimpsests where earlier detail has been erased to allow a new name to be cut into the stone.

What do you do on a drizzly grey day in Berlin? A midwinter day when the sun is enfeebled and hidden, cowering somewhere beneath a thick duvet of cloud. What do you do in a city that you do not know well and only have experience of in winter?

What do you do on a drizzly grey day in Berlin? A midwinter day when the sun is enfeebled and hidden, cowering somewhere beneath a thick duvet of cloud. What do you do in a city that you do not know well and only have experience of in winter?