Ferris wheel, Toktogul, Kyrgyzstan

Ferris wheel, Toktogul, Kyrgyzstan

One of the enduring images from Pripyat, the main town in Ukraine’s Chernobyl disaster region, is that of an abandoned amusement park. A totem for the fall from innocence, here are rides that children once played upon but will never do so again. Rising above the park is an abandoned yellow Ferris wheel – a dejected structure that has fallen in grace from a onetime wheel of fun and joy to a symbol of nuclear catastrophe.

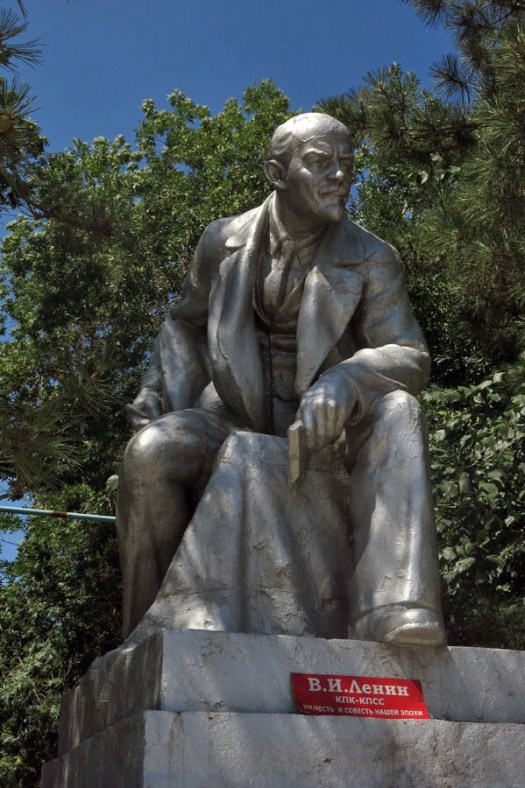

At one time Ferris wheels could found in most Soviet towns of a certain size. One former SSR state I know better than most is the central Asian republic of Kyrgyzstan, a country named after the once-nomadic people indigenous to the region. With three revolutions now since its independence in 1991, it is classic example of a territory in transition, a new country of arbitrarily imposed political boundaries that is still trying to find its feet.

View of Manas Square from Bishkek Ferris wheel, Kyrgyzstan

View of Manas Square from Bishkek Ferris wheel, Kyrgyzstan

To my knowledge there are at least four Ferris wheels that stand in Kyrgyzstan today, although there may be more. The one in Panfilov Park in the heart of the Kyrgyz capital Bishkek has been upgraded in recent years to replace the somewhat creakier Soviet-era one that stood before. Kyrgyzstan’s second city of Osh in the south of the country has another. This Ferris wheel is older (and a little cheaper) than its Bishkek rival and stands in a city park close to the rather desultory canalised river that flows through the city. Alongside the wheel is decommissioned Aeroflot Yak-40 that has been repurposed as a children’s playground. Both Bishkek and Osh wheels afford excellent city views for an outlay of just a few Kyrgyz som.

Panfilov Park, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

Panfilov Park, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

There is another wheel, said to be the largest in the country, in the resort of Bosteri on the north shore of Lake Issyk-Kul but the other Kyrgyzstan Ferris wheel that I have personal experience of can be found in the small town of Toktogul halfway between Bishkek and Osh. Skeletal and long abandoned, this one is found at the edge of a leafy park next to a crumbing sports stadium. Old-fashioned fairground rides can still be found in some of the clearings; the wheel, though, no longer turns. With its seats removed – for their scrap value presumably – and left to the attention of the elements, the wheel, framed against the blue central Asian sky, evokes an air of melancholia. Argumentative crows perpetually flock around the structure as if it had always been theirs to inhabit, taunting its immobility with wheeling flight. At one time this over-sized bicycle wheel delighted children and adults alike with its thrilling views of Toktogul Reservoir and the snow-capped peaks of the Fergana mountains beyond. Now it is a wheel that no longer wheels; a rusting reminder of a half-forgotten past unknown to the children who visit the park today.

Crows and abandoned Ferris wheel, Toktogul, Kyrgyzstan

All photographs ©Laurence Mitchell

If you are curious to discover more about Kyrgyzstan you might want to try this…

There are places that stay in the mind long after visiting. Places that haunt the mind’s memory cache to prevail even years after having set foot there. Such places might be mountains, or rivers, or stretches of coastline; or even villages that charm and bejewel the bedrock of a singular landscape. Usually though, it is a combination of factors that constitutes the essence of such places – earth, sky, water, topography, the patina of a human occupation that beautifies rather than despoils. One such place is Lake Song-Köl in central Kyrgyzstan, the poster girl of a country that has occasionally, and not unreasonably, been described as the most beautiful in the world.

There are places that stay in the mind long after visiting. Places that haunt the mind’s memory cache to prevail even years after having set foot there. Such places might be mountains, or rivers, or stretches of coastline; or even villages that charm and bejewel the bedrock of a singular landscape. Usually though, it is a combination of factors that constitutes the essence of such places – earth, sky, water, topography, the patina of a human occupation that beautifies rather than despoils. One such place is Lake Song-Köl in central Kyrgyzstan, the poster girl of a country that has occasionally, and not unreasonably, been described as the most beautiful in the world.

Kyrgyzstan does not have much of a railway system. A branch line from Moscow extends down from Kazakhstan to Bishkek, the Kyrgyzstan capital; another offers an excruciatingly slow service to Balykchy on Lake Issyk-Kul. Another line extends from Jalal-Abad in the south into Uzbekistan, although trains no longer run on this one. All of these routes date back to Soviet times but even then, Kyrgyzstan, or the the Kyrgyz Soviet Socialist Republic as it was in those days, sat on the outer fringes of the USSR, closer to China than to Moscow. All the more surprising then that, wherever you go in post-independence Kyrgyzstan, you tend to see Soviet-era railway carriages re-located and re-purposed as dwellings, shops, storerooms and even roadside tea-houses. What is most striking is how these are often located far away from a railway line or anything that even resembles a serviceable road. Bump along a rough stony track up to an isolated jailoo (alpine meadow with summer grazing) and the chances are that the nomadic family you meet there will have use of a rusting railway wagon parked somewhere near their yurt. Yurts are ubiquitous in the mountains in summer, and so central to the Kyrgyz way of life that the tunduk, the circular wooden centrepiece of the roof, appears on the national flag. But recycled decommissioned railway wagons have their part to play too, even if rusted metal is less aesthetically pleasing than white felt. In poor countries undergoing rapid transition like Kyrgyzstan, such a resource is too useful to be wasted.

Kyrgyzstan does not have much of a railway system. A branch line from Moscow extends down from Kazakhstan to Bishkek, the Kyrgyzstan capital; another offers an excruciatingly slow service to Balykchy on Lake Issyk-Kul. Another line extends from Jalal-Abad in the south into Uzbekistan, although trains no longer run on this one. All of these routes date back to Soviet times but even then, Kyrgyzstan, or the the Kyrgyz Soviet Socialist Republic as it was in those days, sat on the outer fringes of the USSR, closer to China than to Moscow. All the more surprising then that, wherever you go in post-independence Kyrgyzstan, you tend to see Soviet-era railway carriages re-located and re-purposed as dwellings, shops, storerooms and even roadside tea-houses. What is most striking is how these are often located far away from a railway line or anything that even resembles a serviceable road. Bump along a rough stony track up to an isolated jailoo (alpine meadow with summer grazing) and the chances are that the nomadic family you meet there will have use of a rusting railway wagon parked somewhere near their yurt. Yurts are ubiquitous in the mountains in summer, and so central to the Kyrgyz way of life that the tunduk, the circular wooden centrepiece of the roof, appears on the national flag. But recycled decommissioned railway wagons have their part to play too, even if rusted metal is less aesthetically pleasing than white felt. In poor countries undergoing rapid transition like Kyrgyzstan, such a resource is too useful to be wasted.