Palani, a temple town in western Tamil Nadu, barely gets a mention in the guidebooks. Too close to the hill resort of Kodaikanal to be of much interest other than as a transport hub, the town was a necessary stopover on our rail journey between the Kerala coast and the hyperactive Tamil city of Madurai.

Palani, a temple town in western Tamil Nadu, barely gets a mention in the guidebooks. Too close to the hill resort of Kodaikanal to be of much interest other than as a transport hub, the town was a necessary stopover on our rail journey between the Kerala coast and the hyperactive Tamil city of Madurai.

We arrived in the town just as it was starting to get dark – enough time to have something to eat and wander around the market stalls that stood at the base of the steps that led up to the hilltop temple. The temple, dedicated to the god Murugan, was clearly a big draw for south Indian pilgrims and all the necessary facilities were in place to service their needs. As well as numerous ‘hotels’ offering ‘Pure Veg’ food and a mass of stalls selling mass-produced trinkets and cheap jewellery, a large sign outside a booth offered an ‘Ear Boring’ service, while another advertised itself as ‘Tonsure Centre’, a place dedicated to providing the correct sort of haircut – head shaven with an application of sandalwood paste – for dutiful pilgrims.

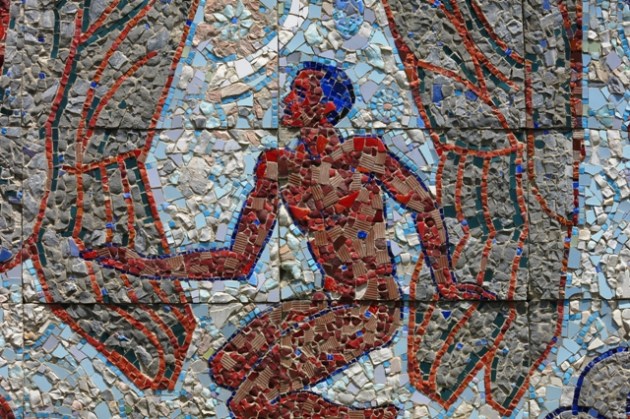

The Murugan Temple – Arulmigu Dandayudhapani Swami Temple to give its full glorious name – stands on a hill above the town. Murugan – aka Muruga, Kartikeya, Skanda, Kumara, Subrahmanya – is a Hindu god of war, a philosopher-warrior figure, son of Parvati and Shiva, who is particularly popular in the southern part of the Indian subcontinent. The temple at Palani is one of six ‘abodes’ (actually, temples) in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu that are dedicated to Murugan. A long flight of stone steps lead up to the top, as does a meandering path for elephants and winched cable car that takes a different, more direct route around the back of the mound.

A little too hot in my hotel room, even under the swishing fan, I dreamed that night of Mark E Smith of The Fall, who in my dream was performing a solo outdoor gig in a Norwich back garden. In the dream world, as in life, Smith was as rambunctious and curmudgeonly as you might expect. He also looked painfully thin, as well he might, and before I woke I recalled mentioning this to someone else present, saying, “I know he’s dead so I suppose this is a dream isn’t it?”

We stepped out into the streets at dawn next morning to make our way to the steps that led up to the temple, leaving our sandals at the bottom before we started the ascent. A line of orange-clad saddhus flanked the base of the steps and scattered by the wayside at various stages of the ascent were gift sellers who touted garlands and puja offerings to present of the shrines above. We were the only foreigners, the only obvious non-Hindus present, yet we were welcomed without fuss. Amplified music of devotional singing accompanied our climb, and mobile phones blazed away around us as we made our way uphill with the other visitors. As everywhere in India, there were numerous friendly requests for selfies – group photos that included us in the frame as some sort of Euro-exotica. This seemed fair exchange, and it was pleasing to know that somewhere out there in the digital ether, in a parallel world to this posting, there existed no small number of images on Instagram and Facebook that included our own heat-flushed faces.

We stepped out into the streets at dawn next morning to make our way to the steps that led up to the temple, leaving our sandals at the bottom before we started the ascent. A line of orange-clad saddhus flanked the base of the steps and scattered by the wayside at various stages of the ascent were gift sellers who touted garlands and puja offerings to present of the shrines above. We were the only foreigners, the only obvious non-Hindus present, yet we were welcomed without fuss. Amplified music of devotional singing accompanied our climb, and mobile phones blazed away around us as we made our way uphill with the other visitors. As everywhere in India, there were numerous friendly requests for selfies – group photos that included us in the frame as some sort of Euro-exotica. This seemed fair exchange, and it was pleasing to know that somewhere out there in the digital ether, in a parallel world to this posting, there existed no small number of images on Instagram and Facebook that included our own heat-flushed faces.

The steps to the top – I did not count them but estimates range between 550—700 – are rock-cut into the hillside. For those unused to it, it can be oddly sensuous walking barefoot for any distance, especially on stone that is deeply embedded with the patina of human activity – a layering of daubed sandalwood paste and windblown dust compounded by the devout footfall of countless pilgrims. Heading uphill we passed chalked mandalas, small shrines and intriguing side temples with attendant bare-chested priests. Macaque monkeys frolicked in the trees that overhung the steps; a solitary owlet stood sentinel on a branch overlooking the plain below. Some of the more elderly pilgrims struggled with the effort of climbing, and a few reluctant children dragged along by parents complained noisily, but overall the atmosphere was cheerful and relaxed – more holiday fun than holy day solemnity.

The steps to the top – I did not count them but estimates range between 550—700 – are rock-cut into the hillside. For those unused to it, it can be oddly sensuous walking barefoot for any distance, especially on stone that is deeply embedded with the patina of human activity – a layering of daubed sandalwood paste and windblown dust compounded by the devout footfall of countless pilgrims. Heading uphill we passed chalked mandalas, small shrines and intriguing side temples with attendant bare-chested priests. Macaque monkeys frolicked in the trees that overhung the steps; a solitary owlet stood sentinel on a branch overlooking the plain below. Some of the more elderly pilgrims struggled with the effort of climbing, and a few reluctant children dragged along by parents complained noisily, but overall the atmosphere was cheerful and relaxed – more holiday fun than holy day solemnity.

At the top, groups of people were scattered around, snapping family pictures on their phones, eating snacks, waiting patiently for their turn for darshan (a view of the sculpted deity) within the temple itself. Large signs carried warnings about thieves and cheats. We circumambulated the temple clockwise, the scent of incense, jasmine and wood smoke permeating the clear, bright air. This intoxicating cocktail – so evocative, so quintessentially Indian – was my madeleine. Here was the India of old that I knew and loved, a deeply felt nostalgia rooted in time and place that touched a nerve, or rather, caressed it tenderly. Here was something that invoked the emotional memory of previous visits made decades earlier: an echo of that indescribable early morning magic when the deep, ancient culture of the subcontinent seemed to manifest itself in a mysterious yet timeless way. To adopt the epithet used by the late John Peel to describe his favourite band, The Fall, whose erstwhile leader I had so peculiarly dreamed about the previous night, India was ‘always different, always the same’. And it was true, despite rampant modernisation in recent years, India at heart was always different, always the same.

My feature on walking part of the Kumano Kodō pilgrimage trail in Japan will be published in a few days time in Elsewhere journal. Elsewhere is a Berlin-based print journal, published twice a year, dedicated to writing and visual art that explores the idea of place in all its forms, whether city neighbourhoods or island communities, heartlands or borderlands, the world we see before us or landscapes of the imagination.

My feature on walking part of the Kumano Kodō pilgrimage trail in Japan will be published in a few days time in Elsewhere journal. Elsewhere is a Berlin-based print journal, published twice a year, dedicated to writing and visual art that explores the idea of place in all its forms, whether city neighbourhoods or island communities, heartlands or borderlands, the world we see before us or landscapes of the imagination.

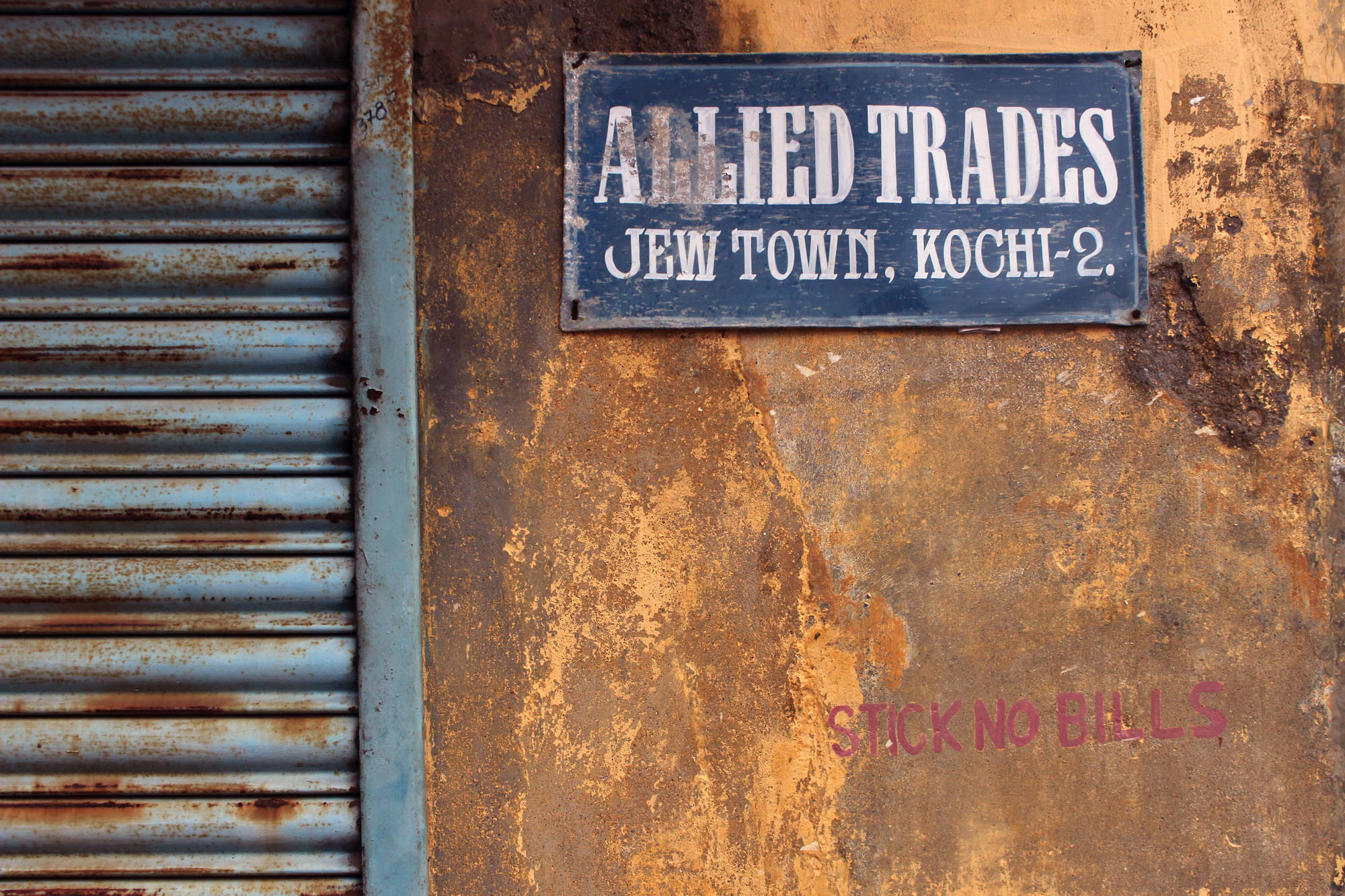

One way of looking at this evocative, if mildly disturbing, place is as a hidden enclave populated with the ghosts of colonialism. Situated right in the middle of Kolkata, tucked away purdah-like from the mayhem of the city streets, the Park Street Cemetery seems like another world. It really is another world: one in which time has coalesced to leave a thick patina on the colonnades and obelisks that commemorate the colonists who created this tropical city in their own image. The colonials mostly died young – easy victims of the disease-ridden, febrile climate that characterised this distant outpost of the East India Company. In true Victorian manner, those who were unfortunate enough to die young and never be able to return to their temperate homeland were interred here in magnificent mausoleums among lush, very un-British vegetation – a tropical Highgate transposed a quarter-way round the world. The cemetery is reputed to be the largest Old World 19th-century Christian graveyard outside Europe. It is also one of the earliest non-church cemeteries, dating from the 1767 and built like much of Kolkata/Calcutta on low, marshy ground. The overall effect is one of Victorian Gothic, although there are also some notable flourishes of Indo-Saracenic vernacular that reflect the influence of Hindu temple architecture.

One way of looking at this evocative, if mildly disturbing, place is as a hidden enclave populated with the ghosts of colonialism. Situated right in the middle of Kolkata, tucked away purdah-like from the mayhem of the city streets, the Park Street Cemetery seems like another world. It really is another world: one in which time has coalesced to leave a thick patina on the colonnades and obelisks that commemorate the colonists who created this tropical city in their own image. The colonials mostly died young – easy victims of the disease-ridden, febrile climate that characterised this distant outpost of the East India Company. In true Victorian manner, those who were unfortunate enough to die young and never be able to return to their temperate homeland were interred here in magnificent mausoleums among lush, very un-British vegetation – a tropical Highgate transposed a quarter-way round the world. The cemetery is reputed to be the largest Old World 19th-century Christian graveyard outside Europe. It is also one of the earliest non-church cemeteries, dating from the 1767 and built like much of Kolkata/Calcutta on low, marshy ground. The overall effect is one of Victorian Gothic, although there are also some notable flourishes of Indo-Saracenic vernacular that reflect the influence of Hindu temple architecture.  Arriving at the gatehouse my name is recorded in a ledger by a lugubrious guard, an action that in itself carries the hint of entering some sort of forbidden zone, a place where the living are only tolerated and should not outstay their welcome. The cemetery seems largely deserted of visitors, although I do inadvertently stumble across a spot of surreptitious man-on-man action taking place in the deep shade of one of the tombs. Despite the funerary setting, there is nothing occult at work here, and I conclude that the young men are simply taking advantage of the privacy offered by the cemetery in this most crowded of all India’s overflowing mega cities. There are signs prohibiting ‘committing nuisance’ attached to some of the trees and I wonder if this is a warning against this sort of clandestine liaison, although in India the expression is usually a euphemism for public urination.

Arriving at the gatehouse my name is recorded in a ledger by a lugubrious guard, an action that in itself carries the hint of entering some sort of forbidden zone, a place where the living are only tolerated and should not outstay their welcome. The cemetery seems largely deserted of visitors, although I do inadvertently stumble across a spot of surreptitious man-on-man action taking place in the deep shade of one of the tombs. Despite the funerary setting, there is nothing occult at work here, and I conclude that the young men are simply taking advantage of the privacy offered by the cemetery in this most crowded of all India’s overflowing mega cities. There are signs prohibiting ‘committing nuisance’ attached to some of the trees and I wonder if this is a warning against this sort of clandestine liaison, although in India the expression is usually a euphemism for public urination.  There are, of course, those who take full advantage of the cemetery’s concentrated occult power – fakirs who use it for training apprentices by making them spend the night here alone, an experience that could never be a comfortable one however much one was inured to the idea of djinns being hyperactive after dark. Even for hard-nosed rationalists, the sense of the numinous here is quite tangible, and the cemetery is without doubt a thoroughly spooky place. This is true even in broad daylight when the taxi horns and traffic thrum from the manic thoroughfare of Mother Teresa Sarani (formerly Park Street; before that, Burial Ground Road) cuts through the trees to provide a background drone for the tuneless squawks of the urban crows and parakeets that loiter here.

There are, of course, those who take full advantage of the cemetery’s concentrated occult power – fakirs who use it for training apprentices by making them spend the night here alone, an experience that could never be a comfortable one however much one was inured to the idea of djinns being hyperactive after dark. Even for hard-nosed rationalists, the sense of the numinous here is quite tangible, and the cemetery is without doubt a thoroughly spooky place. This is true even in broad daylight when the taxi horns and traffic thrum from the manic thoroughfare of Mother Teresa Sarani (formerly Park Street; before that, Burial Ground Road) cuts through the trees to provide a background drone for the tuneless squawks of the urban crows and parakeets that loiter here.  Not requiring of any such thaumaturgic rite of passage, a short afternoon visit suits me just fine. I am left alone with just the crows for company – dark portentous forms that swirl and scatter in the trees above, occasionally coming down to perch scurrilously on the sarcophagi as if they were extras from an Edgar Allen Poe film adaptation. Indeed, this would be the perfect location for a Gothic horror film, especially one that required a steamy colonial setting. Park Street Cemetery is the sort of place where dead souls rising from the ground can seem a distinct possibility – an eerie realm where the hubris of the Raj confronted its own vulnerability and the sad ghosts of empire still linger.

Not requiring of any such thaumaturgic rite of passage, a short afternoon visit suits me just fine. I am left alone with just the crows for company – dark portentous forms that swirl and scatter in the trees above, occasionally coming down to perch scurrilously on the sarcophagi as if they were extras from an Edgar Allen Poe film adaptation. Indeed, this would be the perfect location for a Gothic horror film, especially one that required a steamy colonial setting. Park Street Cemetery is the sort of place where dead souls rising from the ground can seem a distinct possibility – an eerie realm where the hubris of the Raj confronted its own vulnerability and the sad ghosts of empire still linger.