Norfolk doesn’t tend to be the first place that comes into mind when you think of political radicalism but, surprisingly perhaps, there is a strong tradition here and the East Anglian countryside has not always been as true blue as some might have you think.

Norfolk doesn’t tend to be the first place that comes into mind when you think of political radicalism but, surprisingly perhaps, there is a strong tradition here and the East Anglian countryside has not always been as true blue as some might have you think.

Thetford in the Norfolk Brecks is the birthplace of republican and revolutionary pamphleteer Thomas Paine (1737-1809), a man who had an important part to play in both French and American revolutions. Two hundred an fifty years earlier, Robert Kett, a yeoman farmer from Wymondham was another radical figure who became a thorn in the side of the ruling class. It was Kett who, along with his brother, sided with his own impoverished labourers and helped break down fences erected to enclose common land in 1549. Kett’s ragged rebel army camped on Mousehold Heath just outside Norwich before eventually being defeated by government forces, after which Robert Kett was hanged at Norwich Castle, and his brother William at Wymondham Abbey, as an example to uppity peasants.

Another pair of local heroes were Tom and Kitty Higdon who in the first half of the 20th century led the longest strike in British history at their tiny school at Burston in south Norfolk. Here is a brief extract from Slow Travel Norfolk on the subject:

The Burston Strike School

‘The labourer must henceforth take his place industrially socially and politically with the best and foremost of the land.’

Tom Higdon, 1917

In brief, the story goes that Tom and Kitty Higdon were appointed as teachers at Burston School in 1911 after previously working for nine years at Wood Dallingin north Norfolk. The Higdons, who were Christian socialists, had complained about the poor conditions at the Dalling school and the frequent interruption of the children’s education when recruited for farm work. Many of the farmers employing the children were also school managers and tensions mounted as a result of this, particularly as the Higdons had also encouraged local farm labourers to join trade unions. When matters came to a head, the Higdons were given the simple choice of dismissal or removal to a different school.

The couple were transferred to Burston, where they found conditions much the same:their complaints to the school managers, the chairman of whom was the local rector, created tensions here too. The pair were dismissed on fabricated charges of pupil abuse on April Fool’s Day 1914 and, following their dismissal, 66 of the school’s 72 pupils marched along Burston’s ‘candlestick’ (a circular route around the village) carrying placards that bore messages like ‘We Want Our Teachers Back’. Many parents refused to send their children to the official council school and, as a result, a separate ‘strike’ school was established.

The Burston Strike School, as it came to be known, began as little more than a tent on the village green but later moved to a carpenter’s shop in the village. There was considerable intimidation by local employers against the rebel parents and many workers were sacked or evicted from their tied cottages. The village rector, the Reverend Charles Tucker Eland, who firmly believed that labourers should know their place in the social order, also went as far as evicting poor families from church land. Fortunately, the labour shortage created by the onset of World War I worked to the advantage of the labourers. Money was raised by labour organisations such as the Agricultural Labourers’ Union and the Railwaymen and, by 1917, there were sufficient funds to build a new schoolhouse. Both Sylvia Pankhurst and George Lansbury attended the opening ceremony in that same year. The school ran until 1939 when Tom Higdon died and the same modest building serves today as a museum of the strike school’s history. There has been a rally organised by the TGWU held annually in the village since 1984, the 70th anniversary ofthe school’s founding.

An annual rally still takes place in the village each year on the first Sunday in September. It’s a colourful, upbeat affair and a rallying call for what might be described as ‘the old Left’, with speeches by well-known political figures and trades unionists, and music by the likes of Billy Bragg. Regular – indeed, almost annual – speakers were two men who have both sadly passed on this week: Bob Crow and Tony Benn. (The last time I saw Tony Benn here I remember that he recounted the words of Thomas Paine from Rights of Man: ‘My country is the world, my religion is to do good.’)

As 2014 is the centenary year of the strike there is additional event this year on April 1st, but now that both of these two mighty oaks of the Left have fallen it may prove to be a poignant occasion.

![2029[1]](https://eastofelveden.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/20291.jpg?w=525&h=799)

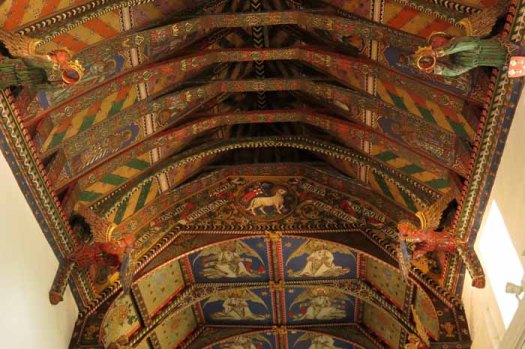

A little way south of Norwich, standing atop what counts for a hill in these parts, is a tiny roundtower church nestled amidst trees. All Saints Church stands above the small village of Keswick in a crumpled corduroy landscape of wintry ploughed fields. Like most of the territory of this urban fringe, the church lies within the acoustic shadow of the city’s southern bypass and the dull thrum of traffic melds with the chatter of birds in the trees and hedgerows – mostly finches, tits and blackbirds at this time of year. Across the valley, a thread of pylons leads inexorably north towards Norwich where they will deliver electricity to power the city’s PlayStations, fridge-freezers and TiVo boxes.

A little way south of Norwich, standing atop what counts for a hill in these parts, is a tiny roundtower church nestled amidst trees. All Saints Church stands above the small village of Keswick in a crumpled corduroy landscape of wintry ploughed fields. Like most of the territory of this urban fringe, the church lies within the acoustic shadow of the city’s southern bypass and the dull thrum of traffic melds with the chatter of birds in the trees and hedgerows – mostly finches, tits and blackbirds at this time of year. Across the valley, a thread of pylons leads inexorably north towards Norwich where they will deliver electricity to power the city’s PlayStations, fridge-freezers and TiVo boxes.