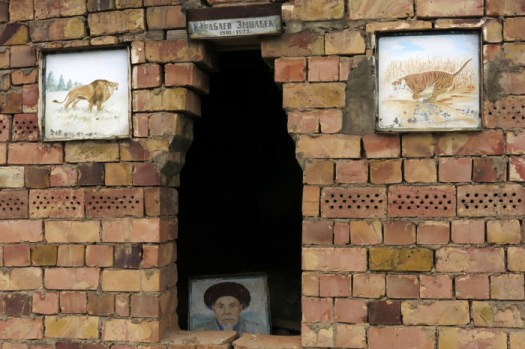

You see them everywhere in Kyrgyzstan. From afar they resemble hillside villages of mud-brick dwellings but a closer look reveals them to be cemeteries. Usually located a little way outside a village, sometimes on top of a low bluff, they are often more impressive than the villages they serve. With a mixture of mud-brick, shrine-like tombs, gravestones with etched images of the deceased, and Islamic crescent moons intermixed with communist five-pointed stars, they represent an odd amalgam of funerary styles. What makes them unmistakably Kyrgyz, though, are the large, wrought-iron, yurt structures that mark many of the graves.

You see them everywhere in Kyrgyzstan. From afar they resemble hillside villages of mud-brick dwellings but a closer look reveals them to be cemeteries. Usually located a little way outside a village, sometimes on top of a low bluff, they are often more impressive than the villages they serve. With a mixture of mud-brick, shrine-like tombs, gravestones with etched images of the deceased, and Islamic crescent moons intermixed with communist five-pointed stars, they represent an odd amalgam of funerary styles. What makes them unmistakably Kyrgyz, though, are the large, wrought-iron, yurt structures that mark many of the graves.

A nomadic people until well into the 20th century, the Kyrgyz used to be buried without fuss wherever they died. Although important nobles and warriors were sometimes honoured with showy mausoleums, most Kyrgyz graves were simple and basic. However, when this nomadic lifestyle was forcibly abandoned during the Soviet period the erection of large memorials to the dead started to become fashionable with the newly sedentary Kyrgyz. It may seem ironic that a wandering people like the Kyrgyz should choose such an earth-bound dwelling after death but a new practice emerged in the 1930s of erecting monuments that recalled their former nomadic lifestyle. As well as the wrought-iron yurt frames that reflected nostalgia for the old way of life, etched portraits – a Russian custom – also started to feature on gravestones. Traces of an altogether more ancient culture became prevalent too: the tradition of pre-Islamic shamanism in which antlers, animal skulls and horses’ tails are used to decorate tombs.

In Kyrgyz graveyards disparate traditions – shamanistic, Islamic, communist – intermingle freely. Gently crumbling as their mud-brick mausoleums slowly decay back into the earth, such cemeteries can be seen far and wide in this central Asian country. Some of the finest are those that can be seen in villages along the Suusamyr Valley in Chui Province. The photos here were taken in two villages in this isolated valley – Kyzyl-Oi and Suusamayr.

In Kyrgyz graveyards disparate traditions – shamanistic, Islamic, communist – intermingle freely. Gently crumbling as their mud-brick mausoleums slowly decay back into the earth, such cemeteries can be seen far and wide in this central Asian country. Some of the finest are those that can be seen in villages along the Suusamyr Valley in Chui Province. The photos here were taken in two villages in this isolated valley – Kyzyl-Oi and Suusamayr.

There will be more on graveyards and many other aspects of Kyrgyz culture in the forthcoming third edition of my book Kyrgyzstan: the Bradt Travel Guide, which will be published early next year.

More information on Kyrgyzstan, including photographs and extracts from the forthcoming book, is available on the Kyrgyzstan page of the Bradt website.

What a wonderful discovery! Usually cemeteries tend to show the worst in religion – but not these.

Fascinating! Thanks 🙂

Fascinating and wonderful mix of signs and symbols.

Fascinating – I am always interested in graveyards but have not seen Kyrgyz examples before.

Very interesting from a region that always seems relatively unknown to me. I love the mix of so many different influences that ought to be odds with each other.

Congratulations to your third edition of the travel guide, Laurence! Fascinating reading about a country totally unknown to me.

Best regards from the four of us in Cley,

Dina

Thank you all for your kind comments. Kyrgyzstan is really a remarkable place, the sort of place that tends to have a ‘best-kept secret’ tag. But, as I have written a guidebook to it, it’s hardly secret any more is it? Now that it’s visa-free and has cheap(ish) flights with Pegasus via Istanbul I would urge anyone to go there. It does help if you like mutton.

Thank you for the context behind why these grave sites are so eclectic!