Just to update the previous post – Nick Marsh, countryside officer at Suffolk Coast and Heaths AONB, went on BBC Radio Suffolk a couple of days ago to talk about my new Cicerone guide and the walking potential that the Suffolk coastal region offers. You can listen again here (fast-forward to around 2:37). It is available online until March 5.

Just to update the previous post – Nick Marsh, countryside officer at Suffolk Coast and Heaths AONB, went on BBC Radio Suffolk a couple of days ago to talk about my new Cicerone guide and the walking potential that the Suffolk coastal region offers. You can listen again here (fast-forward to around 2:37). It is available online until March 5.

Suffolk Coast Walks

![654_FC[1]](https://eastofelveden.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/654_fc1.jpg?w=525) If I might be allowed a little shameless self-publicity, my new book Suffolk Coast and Heaths Walks: Three Long-distance Routes in the AONB is published today by Cicerone. A bit of a mouthful, I know – let’s just call it ‘Suffolk Coast Walks’ for the sake of brevity.

If I might be allowed a little shameless self-publicity, my new book Suffolk Coast and Heaths Walks: Three Long-distance Routes in the AONB is published today by Cicerone. A bit of a mouthful, I know – let’s just call it ‘Suffolk Coast Walks’ for the sake of brevity.

The book gives a detailed account of all three long-distance trails within the Suffolk Coast and Heaths AONB (Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty). All three routes make for excellent walking, either in their entirety or as selected day stages.

OS map extracts for the various stages are included and the book also has considerable background information outlining the history, geography and wildlife of this attractive region.

It is lavishly illustrated too, with photographs taken by yours truly (the cover shows the River Blyth at Southwold).

For a look inside the book, a sample chapter and downloadable PDF file you can visit the Cicerone website here. It is also on Amazon.co.uk here.

Here’s a brief sample from the introduction and a few images from the book.

Introduction

The sky seems enormous here, especially on a bright early summer’s day, and the sea beyond the shingle almost endless. Apart from the gleeful cries of children playing on the beach, the aural landscape is one of soughing waves and the gentle scrape of stones, a few mewing gulls and the piping of oystercatchers. Less than a mile inland, both scenery and soundscape are markedly different – vast expanses of heather, warbling blackcaps in the bushes, and a skylark clattering on high; the warm air is redolent with the almond scent of yellow gorse that seems to be everywhere. This is the Suffolk coast, and it seems hard to imagine that somewhere quite so tranquil is just a couple of hours’ drive away from London.

The big skies, clean air and wide open scenery of the Suffolk coast has long attracted visitors – holiday makers certainly, but also writers, artists and musicians. The Suffolk coast’s association with the creative arts is longstanding, and its attraction is immediately obvious – close enough to the urban centres of southern England for a relatively easy commute, yet with sufficient unspoiled backwater charm for creativity to flourish.

The big skies, clean air and wide open scenery of the Suffolk coast has long attracted visitors – holiday makers certainly, but also writers, artists and musicians. The Suffolk coast’s association with the creative arts is longstanding, and its attraction is immediately obvious – close enough to the urban centres of southern England for a relatively easy commute, yet with sufficient unspoiled backwater charm for creativity to flourish.

It is not hard to see the appeal – east of the A12, the trunk road that more or less carves off this section of the East Anglian coast, there is a distinct impression that many of the excesses of modern life have passed the region by. The small towns and villages that punctuate the coastline and immediate hinterland are by and large quiet, unspoiled places that, while developed as low-key resorts in recent years, still reflect the maritime heritage for which this coast was famous before coastal erosion took its toll.

The county of Suffolk lies at the heart of East Anglia, in eastern England, sandwiched between the counties of Norfolk to the north, Essex to the south and Cambridgeshire to the west. The county town is Ipswich, by far the biggest urban centre in the county, while other important centres include Bury St Edmunds to the west and Lowestoft to the north. Much of the county is dominated by agriculture, especially arable farming, but the coastal region featured in this book has a wider diversity of scenery – with reedbeds, heath, saltmarsh, shingle beaches, estuaries and even cliffs all contributing to the variety. There is also woodland, both remnants of ancient deciduous forests and large modern plantations. Such a variety of landscapes means a wealth of wildlife habitat, and so it is little wonder that the area is home to many scarce species of bird, plant and insect.

The county of Suffolk lies at the heart of East Anglia, in eastern England, sandwiched between the counties of Norfolk to the north, Essex to the south and Cambridgeshire to the west. The county town is Ipswich, by far the biggest urban centre in the county, while other important centres include Bury St Edmunds to the west and Lowestoft to the north. Much of the county is dominated by agriculture, especially arable farming, but the coastal region featured in this book has a wider diversity of scenery – with reedbeds, heath, saltmarsh, shingle beaches, estuaries and even cliffs all contributing to the variety. There is also woodland, both remnants of ancient deciduous forests and large modern plantations. Such a variety of landscapes means a wealth of wildlife habitat, and so it is little wonder that the area is home to many scarce species of bird, plant and insect.

This region can be broadly divided into three types of landscape – coast, estuary and heathland, or Sandlings as they are locally known – and the three long-distance walks described in this guide are each focused on one of these landscape types. All three have plenty to offer visitors in terms of scenery, wildlife and historic interest, and the footpaths, bridleways and quiet lanes found here make for excellent walking.

Almost all of the walks featured here fall within the boundaries of the Suffolk Coast and Heaths Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB), which stretches south from Kessingland in the north of the county to the Stour estuary in the south. The whole area – both coast and heaths – is now one of 47 Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, having received AONB status in 1970, a designation that recognises, and protects, the area’s unique landscape.

Almost all of the walks featured here fall within the boundaries of the Suffolk Coast and Heaths Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB), which stretches south from Kessingland in the north of the county to the Stour estuary in the south. The whole area – both coast and heaths – is now one of 47 Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, having received AONB status in 1970, a designation that recognises, and protects, the area’s unique landscape.

Pink

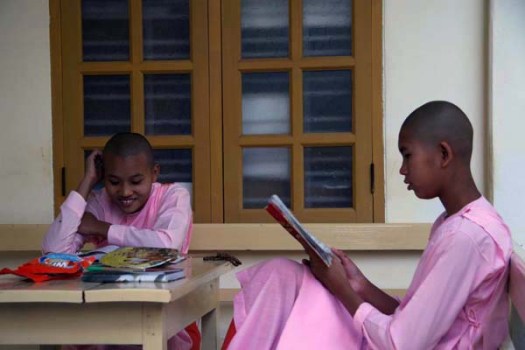

I will let the pictures do most of the talking in this post.

Buddhist nuns in Myanmar always dress in a fetching pink colour. A nun’s life is tough but they seem cheerful enough, collecting alms in the market, studying Pali sutras or sorting out clothes at the nunnery. The commitment is actually finite, as most Burmese girls only join the nunnery for a period of a few weeks at a time.

Buddhist nuns in Myanmar always dress in a fetching pink colour. A nun’s life is tough but they seem cheerful enough, collecting alms in the market, studying Pali sutras or sorting out clothes at the nunnery. The commitment is actually finite, as most Burmese girls only join the nunnery for a period of a few weeks at a time.

As with Burmese boys, time spent in monasteries is viewed as a right of passage and it is considered an honour for the family to have their child wear robes for even a short period. Naturally, it brings good karma too.

Young nuns at Mingun nunnery and at Amarapura market, Myanmar

The character below is actually a boy, despite the makeup and pink get-up. He is on his way to a monastery to become a monk for a few weeks. The boy is accompanied by villagers who sing stirring valedictory songs to him as he rides along on his pony. Most of the village seems to go along for the ride – it is a party atmosphere and drink (palm toddy perhaps) has certainly been taken by some of the happy entourage. Remarkable as it may seem, this is the sort of chance event that you stumble upon every day of the week in Myanmar.

Young novice processing to Buddhist monastery near Hpa-an, Myanmar

Young novice processing to Buddhist monastery near Hpa-an, Myanmar

The Road to Moulmein

‘By the old Moulmein pagoda lookin’ lazy at the sea

There’s a Burma girl a-settin’ and I know she thinks o’ me’

These words by Rudyard Kipling form the opening lines of the Road to Mandalay, an evocative poem that manages to capture the mysterious spirit of the East as seen through Western eyes. The work holds such an important place in the colonial canon that it comes as a surprise to discover that Kipling only spent a total of three days in Burma (now known as Myanmar). What is more, he never actually set foot in Mandalay itself. He did, however, briefly visit the southern coastal city of Moulmein (now known as Mawlamyine or Mawlamyaing) and it was the sight of a beautiful Burmese girl climbing the hill on her way to the city’s Kyaikthanlan Paya pagoda that inspired Kipling’s muse in this instance.

Kyaikthanlan Paya is the most prominent of a number of glistening Buddhist stupas that line the high ridge bisecting the city. Having arrived in Moulmein by means of a nine-hour train journey from Yangon in which the buckled rails made us bounce in our seats like cantering equestrians, a leg stretch seemed in order and there was just enough time to pay a visit to the pagoda before darkness fell. As things turned out I did not walk all the way up to the top as halfway up to the temple complex an elderly gentleman stopped to offer me a pillion ride on his motorbike. Such events are not out of the ordinary in Myanmar; after just a couple of days in the country I was already aware that thoughtful yet undemonstrative gestures like this were commonplace.

Watching the sun set over the sea from the viewpoint beneath the temple I met another old man who seemed delighted when I told him I was English. I am not sure if this was because he simply approved of my nationality or whether he was just pleased to have the opportunity to use the English he had learned long ago in school. Either way, the warmth seemed entirely genuine. ”It is a pleasure to see you here. I do hope we can meet here again”. (We did, the following day).

As previously mentioned, Kipling did not spend long in Moulmein – just enough time to pen his famous poem and take a fancy to a local beauty. The novelist George Orwell, on the other hand, had a far stronger relationship with the city. Orwell’s mother’s family came from Moulmein and it was also here that he underwent training with the Burma Police Force. This and subsequent Burmese experience would provide raw material for Burmese Days, his first novel and a damning account of British colonial life in which most of the colonial characters seems to be alcoholic, racist or both.

Moulmein also provides the background for Orwell’s 1936 memoir Shooting an Elephant, a work that opens with the arresting line:

Moulmein also provides the background for Orwell’s 1936 memoir Shooting an Elephant, a work that opens with the arresting line:

‘In Moulmein, in Lower Burma I was hated by large numbers of people – the only time in my life that I have been important enough for this to happen to me.’